In this recipe, we will give an introduction to IPython and Jupyter for data analysis. Most of the subject has been covered in the prequel of this book, Learning IPython for Interactive Computing and Data Visualization, Second Edition, Packt Publishing, but we will review the basics here.

We will download and analyze a dataset about attendance on Montreal's bicycle tracks. This example is largely inspired by a presentation from Julia Evans (available at https://github.com/jvns/talks/blob/master/2013-04-mtlpy/pistes-cyclables.ipynb). Specifically, we will introduce the following:

Data manipulation with pandas

Data visualization with Matplotlib

Interactive widgets

The very first step is to import the scientific packages we will be using in this recipe, namely NumPy, pandas, and Matplotlib. We also instruct Matplotlib to render the figures as inline images in the Notebook:

>>> import numpy as np import pandas as pd import matplotlib.pyplot as plt %matplotlib inlineNow, we create a new Python variable called

urlthat contains the address to a Comma-separated Values (CSV) data file. This standard text-based file format is used to store tabular data:>>> url = ("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/" "ipython-books/cookbook-2nd-data/" "master/bikes.csv")pandas defines a

read_csv()function that can read any CSV file. Here, we pass the URL to the file. pandas will automatically download the file, parse it, and return a DataFrame object. We need to specify a few options to make sure that the dates are parsed correctly:>>> df = pd.read_csv(url, index_col='Date', parse_dates=True, dayfirst=True)The

dfvariable contains a DataFrame object, a specific pandas data structure that contains 2D tabular data. Thehead(n)method displays the firstnrows of this table. In the Notebook, pandas displays a DataFrame object in an HTML table, as shown in the following screenshot:>>> df.head(2)

Here, every row contains the number of bicycles on every track of the city, for every day of the year.

We can get some summary statistics of the table with the

describe()method:>>> df.describe()

Let's display some figures. We will plot the daily attendance of two tracks. First, we select the two columns,

Berri1andPierDup. Then, we call theplot()method:>>> df[['Berri1', 'PierDup']].plot(figsize=(10, 6), style=['-', '--'], lw=2)

Now, we move to a slightly more advanced analysis. We will look at the attendance of all tracks as a function of the weekday. We can get the weekday easily with pandas: the

indexattribute of the DataFrame object contains the dates of all rows in the table. This index has a few date-related attributes, includingweekday_name:>>> df.index.weekday_name Index(['Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday', 'Monday', 'Tuesday', ... 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday', 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday'], dtype='object', name='Date', length=261)To get the attendance as a function of the weekday, we need to group the table elements by the weekday. The

groupby()method lets us do just that. We useweekdayinstead ofweekday_nameto keep the weekday order (Monday is0, Tuesday is1, and so on). Once grouped, we can sum all rows in every group:>>> df_week = df.groupby(df.index.weekday).sum() >>> df_week

We can now display this information in a figure. We create a Matplotlib figure, and we use the

plot()method of DataFrame to create our plot:>>> fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(10, 8)) df_week.plot(style='-o', lw=3, ax=ax) ax.set_xlabel('Weekday') # We replace the labels 0, 1, 2... by the weekday # names. ax.set_xticklabels( ('Monday,Tuesday,Wednesday,Thursday,' 'Friday,Saturday,Sunday').split(',')) ax.set_ylim(0) # Set the bottom axis to 0.

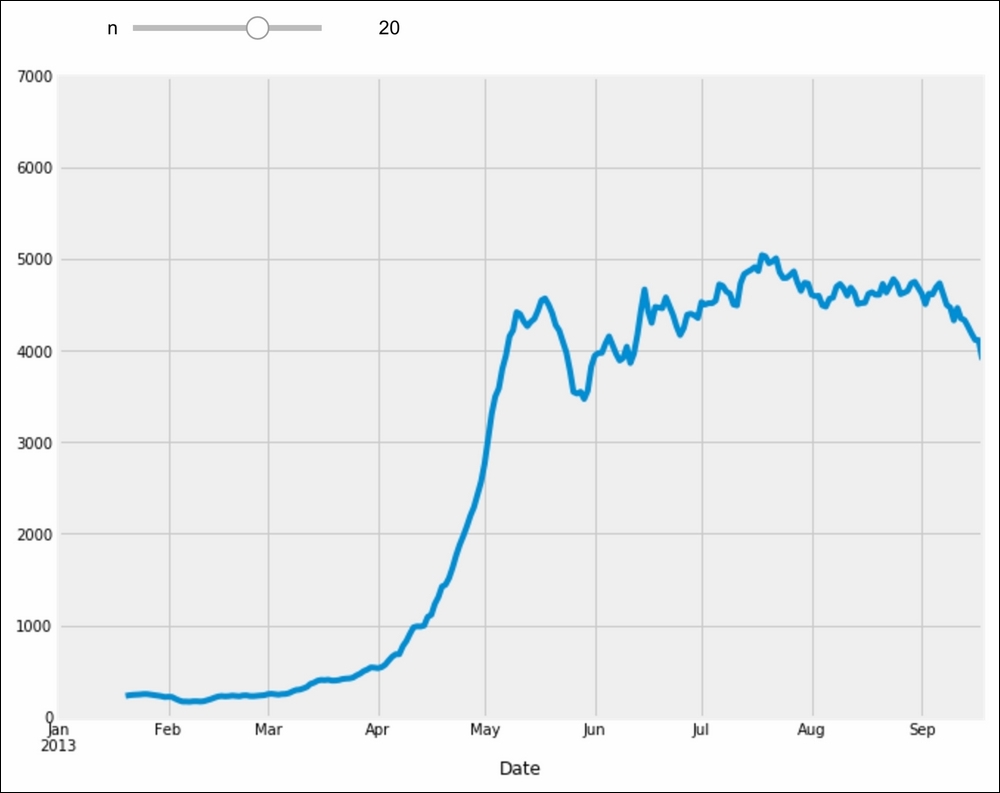

Finally, let's illustrate the interactive capabilities of the Notebook. We will plot a smoothed version of the track attendance as a function of time (rolling mean). The idea is to compute the mean value in the neighborhood of any day. The larger the neighborhood, the smoother the curve. We will create an interactive slider in the Notebook to vary this parameter in real time in the plot. All we have to do is add the

@interactdecorator above our plotting function:>>> from ipywidgets import interact @interact def plot(n=(1, 30)): fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(10, 8)) df['Berri1'].rolling(window=n).mean().plot(ax=ax) ax.set_ylim(0, 7000) plt.show()

To create Matplotlib figures, it is good practice to create a Figure (fig) and one or several Axes (subplots, ax object) objects with the plt.subplots() command. The figsize keyword argument lets us specify the size of the figure, in inches. Then, we call plotting methods directly on the Axes instances. Here, for example, we set the y limits of the axis with the set_ylim() method. If there are existing plotting commands, like the plot() method provided by pandas on DataFrame instances, we can pass the relevant Axis instance with the ax keyword argument.

pandas is the main data wrangling library in Python. Other tools and methods are generally required for more advanced analyses (signal processing, statistics, and mathematical modeling). We will cover these steps in the second part of this book, starting with Chapter 7, Statistical Data Analysis.

Here are some more references about data manipulation with pandas:

Learning IPython for Interactive Computing and Data Visualization, Second Edition, Packt Publishing, the prequel of this book

Python for Data Analysis, O'Reilly Media, by Wes McKinney, the creator of pandas, at http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920023784.do

Python Data Science Handbook, O'Reilly Media, by Jake VanderPlas, at http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920034919.do

The documentation of pandas available at http://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/

Usage guide of Matplotlib, at https://matplotlib.org/tutorials/introductory/usage.html