The "Accidental Manager" is perhaps ubiquitous now more than ever, but the concept has been around for a long time. The Peter Principle, by Laurence J. Peter, introduced the concept that people successful in their role are promoted until they reach a level where they are no longer competent, and that was published back in 1969!

This idea was further popularized by the Dilbert cartoons, in which the Dilbert Principle mocks the notion that the least competent people are given more managerial responsibilities and power, which is often misused. Quite simply, the "Accidental Manager" can be characterized by a person who reluctantly, unknowingly, unintentionally, or inadvertently becomes a manager.

Perhaps the people management responsibility has defaulted to the "Accidental Manager" because the incumbent manager is too busy, or perhaps the organization has created the new position and has mandated that a person from the existing hierarchy and team takes on the post.

It is of course possible that the manager position has been removed altogether to reduce headcount, but all their responsibilities still need to be picked up by someone, or perhaps the organization has struggled to recruit for this position from the labor market, and "you're it" until they find someone better! There are many circumstances where an accidental manager is created.

In the organization's defense, from their perspective, succession and continuity are rarely easy. Taken to the extreme, the alternative would be to promote someone who is clearly struggling in their current role. Out of the two choices, it's logical to opt for the seemingly more reasonable option. So, if you are an accidental manager, take it as a compliment and confidence booster. It's in your organization's interest to set you up to succeed, and there are people who believe you are capable of becoming a manager.

Rewarding underperformance, as opposed to achievement, could be seen as a blow to the morale of others and a cultural disaster affecting the organization's core people values. It would be a realization of the Dilbert Principle! Ask yourself the following questions:

- You're a brilliant developer. Can you manage the team as well?

- You're a brilliant developer. Can you manage some projects, too?

So, what does all this mean to you, and how can you understand it and use it to your advantage? For argument's sake, let's say you are a brilliant developer, probably the best among your peers as recognized by the organization. In that case, there's a chance you could become an accidental manager if the circumstances arise, and perhaps you already are. Being an accidental manager can be interpreted as a purely negative thing, a lesser version of what you may think of as being a "real manager," but let's be clear - it is not!

Circumstances create the accidental manager, but they don't define the person in this position. The key to making this accidental journey a success is to embrace it and get the required training and support – as little or as much as you need, when you need it.

Recognizing that you may not know what you need is an important first step. It is also an ongoing management skill to learn as you develop, which we will discuss later in the book. So, part of the support structure you will need around you is someone who will constructively point out your blind spots.

Everybody has blind spots, so spot them early instead of ignoring them. In fact, the Johari Window, which you can see in Figure 1.3, allows you to think about your own strengths and weaknesses, your blind spots, and ways or people that can help detect them:

Figure 1.3: Johari Window

Source: https://www.successfulculture.com/build-more-self-awareness-stronger-culture-using-johari-window/

One key thing for all managers to avoid, but especially for accidental managers, is what technologist and writer Peter Gillard-Moss calls imposter syndrome. This is when an often newly promoted manager feels compelled to show that they know everything, even when they don't.

When imposter syndrome sets in for a manager, an array of negative behaviors and impacts can result, including becoming ever more insecure about your position of responsibility and alienating your own team because you're killing their motivation to collaborate and be creative. Not to mention that the manager is stressing themselves out by trying to stay on this treadmill, which only goes faster and faster, even if they're still going at the same speed. The most common way to be a victim of imposter syndrome is to believe that your superior technical ability and/or experience entitles you to be a manager and to lead.

A simple hack to avoid imposter syndrome is to recognize and admit that there will always be things you don't know and aren't even aware that you don't know! This is what makes the journey interesting, and you should never be in denial that there is still so much to learn, no matter how much you think you already know.

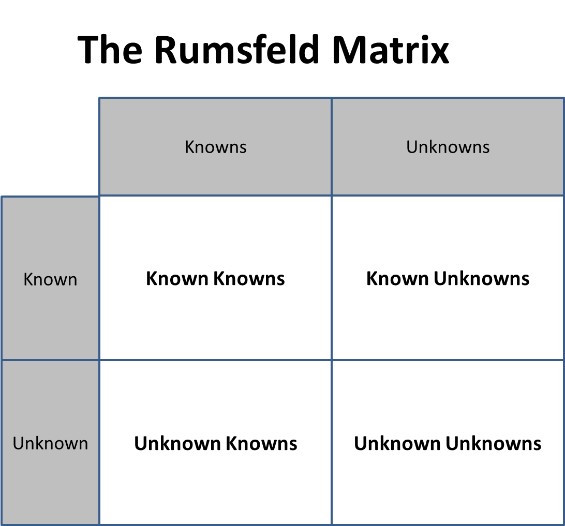

On the other hand, it is important to keep this in balance with what you do know. One of the key tools to achieve this is the Known/Unknown matrix, or the Rumsfeld Matrix, which was made famous by Donald Rumsfeld, the former U.S. Secretary of Defense. This chart can be a valuable tool to track your progress and ongoing development as a manager.

The first version you produce will give you an idea of where you need to focus your efforts on learning initially, and, as you repeat the exercise regularly, you can use it to assess your proportion of knowns and unknowns.

As you become more experienced and confident as a manager, you will trend toward more knowns versus unknowns. The idea is not to eliminate all unknowns, but to simply understand what they might be, while affirming and reaffirming the things you are knowledgeable and confident on. Here is an image of the Rumsfeld Matrix:

Figure 1.4: The Rumsfeld Matrix

As an accidental manager, you may not have had the time or opportunity to prepare for the new responsibilities to shape the role before being "it." You can, and should, use this to your advantage. As a newly bestowed accidental manager, you need to maximize the opportunity to ask open and unassuming questions. Tell people that while you don't know something, you want to learn, using open questions like these:

- Where can I get more information on this?

- What are the pros and cons of this process?

- Can you help us to improve this?

Ultimately, as you learn more, your proportion of unknowns will decrease, while the proportion of knowns will increase. As a result, you'll progress along the learning curve, which is no different from learning a new technology as a developer.

When you start, you are likely to have more unknowns than knowns, and you'll be asking more questions than answers. But don't – and never let yourself – be put off! You are still adding value by asking these questions, both to yourself and to the team and organization.

In fact, asking the right questions is often cited as the most important and powerful skill in senior management. This is often referred to as part of corporate governance. Think about the latest corporate scandals and crises in large-scale organizations, which are often traced back to a lack of adequate corporate governance. Those at the very top can fail to recognize the impending cliff edge that the organization is headed toward until it's too late.

To be reasonable, a manager is not expected to know absolutely everything that is happening at any one time. This reinforces the need to ask judicious questions at the right moment, and, in return, getting truthful and insightful answers back. Especially as an accidental manager, one of the key behaviors you should learn and demonstrate early on is the canny shrewdness to ask challenging questions. This has the power to make people respect you, even if your domain knowledge level is low.