Most developers and architects will be familiar with the concept of a pattern – a good solution to a recurring problem within an architectural domain described in a formalized and reusable way. Some classic examples include the following:

- Singleton: A software design pattern that limits the number of instances of a given type to one.

- Fire-and-forget: An asynchronous integration pattern that sends off a message from a computational context and proceeds without waiting for a response.

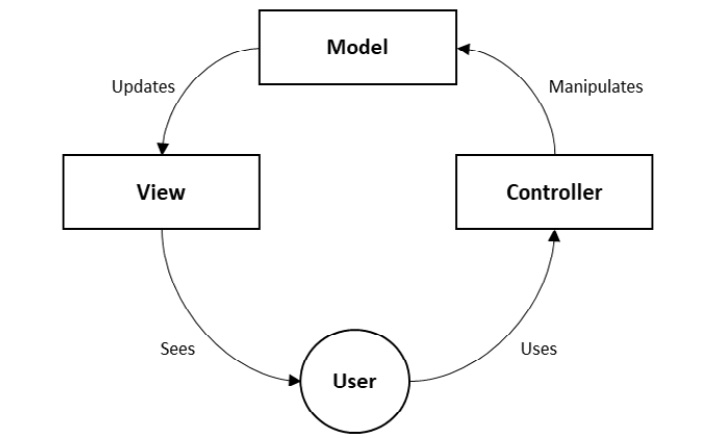

- Model-View-Controller (MVC): An architectural pattern that divides an application into three tiers with specifically defined responsibilities:

- First, a model maintains the state of the application and is responsible for any changes to data

- Second, a view shows a particular representation of that model to an end user via some interface

- Third, a controller implements the business logic that responds to events in the user interface or changes in the model and does the necessary mediation between the view and the model

This pattern is shown in the following diagram:

Figure 1.1 – MVC pattern diagram

Patterns such as these have been defined at many levels of abstraction and for many different platforms.

References

You can look at the following resources to get a good introduction to the various patterns that one can apply from a Salesforce perspective.

The integration patterns guide lists all the main patterns to use when designing Salesforce integrations: https://developer.salesforce.com/docs/atlas.en-us.integration_patterns_and_practices.meta/integration_patterns_and_practices/integ_pat_intro_overview.htm. In a Salesforce world, this may be the most commonly referenced set of patterns as they are ubiquitous for integration design.

The book Apex Design Patterns from Packt, by Anshul Verma and Jitendra Zaa, provides patterns at the software design level and the concrete code level for the Apex language.

The Salesforce Architects site, while new, contains a range of patterns across domains, from code-level specifics to reference architectures and solution kits to good patterns for selecting governance: https://architect.salesforce.com/design/#design-patterns.

The point is that we have lots of good patterns to choose from on the Salesforce platform, many that are provided by Salesforce themselves, others by the wider community. Many patterns that apply to other platforms are also relevant to us and we learn much by studying them.

But this is a book about anti-patterns, not patterns. So why am I starting with a discussion about patterns? It turns out that the two are nearly inseparable and originate in the same tradition. Understanding anti-patterns, therefore, begins with an understanding of what a pattern is. Indeed, one common form of anti-patterns is a design pattern that has been misapplied. We will explore this in the next section.

From pattern to anti-pattern

The design pattern movement in software architecture originates from the work of Christopher Alexander, an architect whose job was to design buildings rather than systems. In his work The Timeless Way of Building, he introduced a pattern template for physical architecture that consisted of a name, a problem statement, and a solution in a standardized format.

The rhetorical structure provided by the Alexandrian template was rapidly adopted by architects of a different kind, the ones that build software. They recognized the power of a standardized way to describe problem-solution sets for communicating good practice. With the publication of the classic Gang of Four book, Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, the use of patterns became mainstream within software development and remains so to this day.

The research on patterns inspired an incipient community of practitioners and researchers in software engineering to think about failure modes of software systems analogously to how design patterns were being used. This happened over an extended period of time, and it isn’t possible to point to anyone in the anti-patterns movement that can be seen as the genuinely foundational figure.

However, many research papers on the topic start with the definition given by Andrew Koening in the Journal of Object-Oriented Programming in 1995. This definition says that an anti-pattern is very similar to a pattern and can be confused for one. However, using it does not lead to a solution, but instead has negative consequences.

That definition captures much of the essence and can be usefully combined with the following thoughts from Jim Coplien, another early pioneer. He thought that good patterns in and of themselves were not sufficient to define a successful system. You also have to be able to show that anti-patterns are absent.

In a nutshell, then, an anti-pattern is a pattern that occurs in unsuccessful software systems or projects that can look superficially like a good solution but in practice gets you into trouble. Some common anti-patterns that have been around for ages and are still relevant include the following:

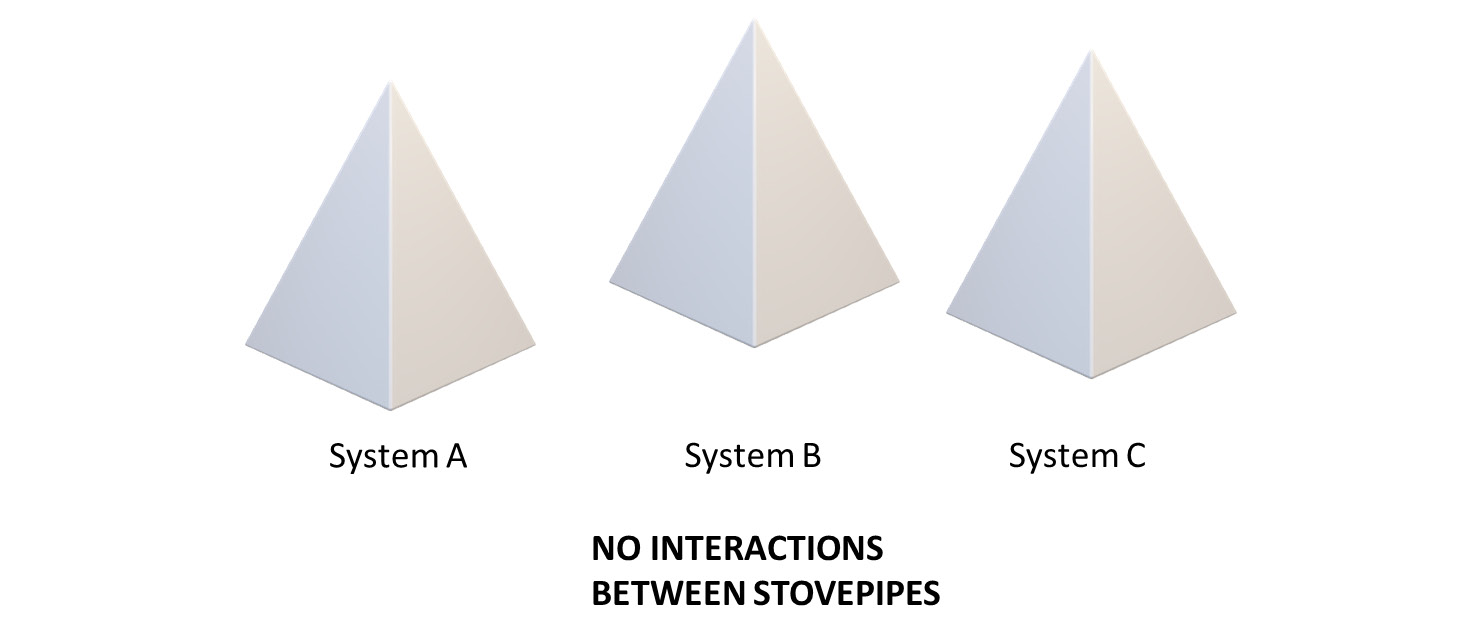

- Stovepipe: A system or module that is effectively impossible to change because of how its interfaces are designed. See the following diagram for an illustration:

Figure 1.2 – The Stovepipe anti-pattern

- Blob: A design where a single class effectively encapsulates all the business logic and functionality, leading to major maintenance headaches.

- Intensive coupling: A design that uses an excessively large number of methods from another class or module in implementing a feature, leading to a deep dependency that is hard to understand or change.

We’ll dig into all these anti-patterns from a Salesforce perspective in later chapters, underscoring the unfortunate fact that Salesforce, while a great platform, is still a software system prone to the kind of mistakes that have plagued software systems for decades. If this were not the case, then, of course, there’d be no need for this book or, for that matter, for Salesforce architects.

Having discussed the historical origins of anti-patterns, we will now discuss how they arise in the real world.

Where do anti-patterns come from?

Anti-patterns tend to arise again and again because the circumstances that drive technology projects into trouble are at least somewhat predictable. Equally predictable are the responses of people put into those situations and as people in tough spots frequently make the same bad decisions, we get systematic patterns to study.

Generally speaking, the most important thing to remember about anti-patterns is that they seem like a good idea at the time. They aren’t simply bad practices that someone should know better than to apply. You can make a reasoned argument that they should lead to good or at least acceptable outcomes when applied.

Sometimes the decision to apply an anti-pattern is down to inexperience, and sometimes it is down to desperation. But as often as not, it is down to experienced professionals convincing themselves that in this case, doing what they’re doing is actually the right call or that this situation really is different.

We will try to reflect this diversity of origins in the examples we show throughout this book. However, to do this, we first need to show how we will present the examples in a consistent way to enable learning.

An anti-pattern template

One of the key characteristics of both patterns and anti-patterns is that they are written using a recognizable template. Many templates have been suggested over the course of the years, some more elaborate than others.

The template we will use in this book contains the bare bones that recur in nearly all existing anti-pattern templates. However, we do not include a great number of optional elements. Most additional elements that are included in other templates serve to ease categorization or cross-referenceability. Those are highly desirable elements to have when creating a searchable catalog of patterns or anti-patterns but are less useful in a printed book. Therefore, we omit them and instead include the following elements:

- Name: An easy-to-remember moniker for the pattern that serves to identify it uniquely and help discourse among architects.

- Type: In this book, we categorize our anti-patterns by the domain from the Certified Technical Architect (CTA) review board examination that they are relevant to. This is both to help people on the CTA journey, but also because this is a familiar typology for Salesforce architects.

- Example: We will introduce each anti-pattern by giving an example of how it might occur. The examples will be fictional but grounded in real-world events. This will frame the anti-pattern and give you an immediate understanding of the issues involved before delving deep into the nuts and bolts.

- Problem: This section describes more formally the problem or problems that the anti-pattern purports to solve. These are the real issues that the anti-pattern is meant to be a solution for, although using it in practice will turn out to be a bad idea.

- Proposed solution: How the anti-pattern claims to solve the problem described in the previous section and how that can be tempting to believe given certain circumstances.

- Results: In the results section, we outline what results you can expect from applying the anti-pattern along with its main variations. We go into the detail of why this is a bad solution, although it might look good at the outset.

- Better solutions: The final section in the template will tell you what to do instead when faced with the problem that is the basis for the anti-pattern. Not all problems have easy solutions, but you can generally do better than applying an anti-pattern.

Now that we have an understanding of what anti-patterns are and how they are going to be structured in this book, we will move on to explaining how you, as an architect, can improve your skills by using them to learn.

Free Chapter

Free Chapter