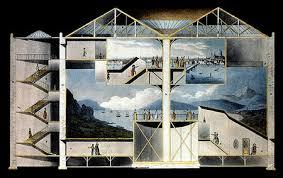

Along the way, artists began to experiment with large-scale paintings, that were so large they would eclipse the viewer's entire field of view, enhancing the illusion that one was not simply in the theater or gallery, but on location. The paintings would be curved in a semi-circle to enhance the effect, the first of which may have been created in 1791 in England by Robert Barker. They proved so financially successful that over 120 different Panorama installations were reported between 1793 and 1863 in London alone. This wide field-of-view solution used to draw audiences would be repeated by Hollywood in the 1950s with Cinerama, a projection system that required three synchronized cameras and three synchronized projectors to create an ultra-wide field of view. This was again improved on by Circle Vision 360 and IMAX over the years:

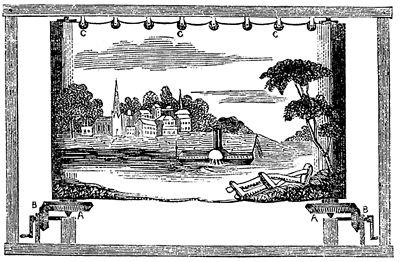

For a brief period of time, these large-scale paintings were taken even a step further with two enhancements. The first was to shorten the field of view to a narrower fixed point, but to make the image very long—hundreds of meters long, in fact. This immense painting would be slowly unrolled to an audience, often through a window to add an extra layer of depth, typically and with a narrated tour guide, thus giving the illusion that they were looking out of a steamboat window, floating down the Mississippi (or the Nile) as their guide lectured about the flora and fauna that drifted by.

As impressive as this technology was, it had first been used centuries earlier by the Chinese, though on a smaller scale:

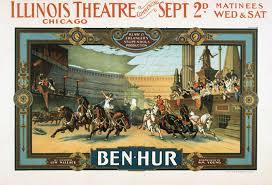

A version of this mechanism was used in the 1899 Broadway production of Ben-Hur, which ran for 21 years and sold over 20 million tickets. One of the advertising posters is shown here. The actual result was a little different:

A giant screen of the Roman coliseum would scroll behind two chariots, pulled by live horse while fans blew dust, giving the impression of being on the chariot track in the middle of the race. This technique would be used later in rear-screen projections for film special effects, and even to help land a man on the moon, as we shall see:

The next step was to make the painting rotate a full 360 degrees and place the viewer in the center. Later versions would add 3D sculptures, then animated lights and positional scripted audio, to further enhance the experience and blur the line between realism and 2D painting. Several of these can still be seen in the US, including the Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.