Now that you have learned about the purpose of TypeScript, it's time to get our hands dirty and start writing some code.

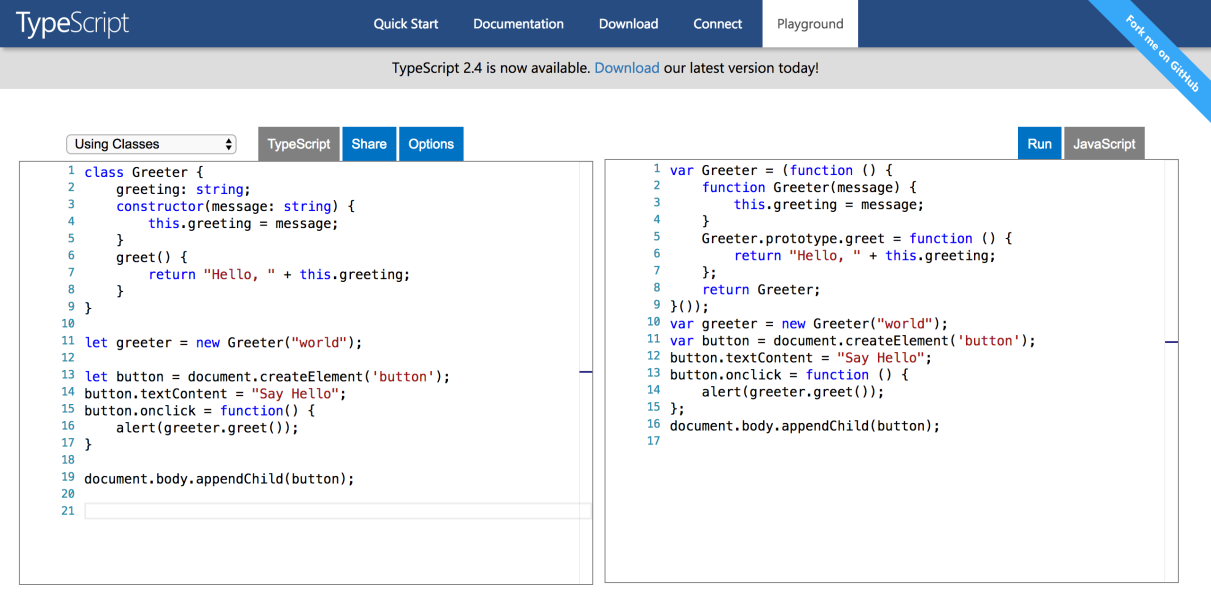

Before you can start learning how to use some of the basic TypeScript building blocks, you will need to set up your development environment. The easiest and fastest way to start writing some TypeScript code is to use the online editor, available on the official TypeScript website at https://www.typescriptlang.org/play/index.html:

The preceding screenshot shows the appearance of the TypeScript playground. If you visit the playground, you will be able to use the text editor on the left-hand side of the screen to write TypeScript code. The code will then be automatically compiled into JavaScript. The output code will be inserted in the text editor located on the right-hand side of the screen. If your TypeScript code is invalid, the JavaScript code on the right-hand side will not be updated.

Alternatively, if you prefer to be able to work offline, you can download and install the TypeScript compiler. If you work with a Visual Studio version older than Visual Studio 2015, you will need to download the official TypeScript extension from https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/. If you are working with a version of Visual Studio released after the 2015 version (or Visual Studio Code), you will not need to install the extension, as these versions includes TypeScript support by default.

You can also use TypeScript from the command-line interface by downloading it as an npm module. Don't worry if you are not familiar with npm. For now, you only need to know that it stands for node package manager and is the default Node.js package manager. Node.js is an open source, cross-platform JavaScript runtime environment for executing JavaScript code server-side. To be able to use npm, you will need to install Node.js in your development environment. You will be able to find the Node.js installation files on the official website at https://nodejs.org/.

Once you have installed Node.js in your development environment, you will be able to run the following command in a console or Terminal:

npm install -g typescript

sudo npm install -g typescript

Create a new file named test.ts, and add the following code to it:

let myNumberVariable: number = 1; console.log(myNumberVariable);

Save the file into a directory of your choice and open a command-line interface. Navigate to the directory in which you saved the file and execute the following command:

tsc test.ts

If everything goes well, you will find a file named test.js in the same directory in which the test.ts file is located. Now you know how to compile your TypeScript code into JavaScript code.

You can execute the output JavaScript code using Node.js:

node test.js

Now that we know how to compile and execute TypeScript source code, we can start learning about some of the TypeScript features.