So how does BizTalk Server actually work? At its core, BizTalk Server is an event-processing engine based on a conventional publish-subscribe pattern. Wikipedia defines the publish-subscribe pattern as:

"An asynchronous messaging paradigm where senders (publishers) of messages are not programmed to send their messages to specific receivers (subscribers). Rather, published messages are characterized into classes, without knowledge of what (if any) subscribers there may be. Subscribers express interest in one or more classes, and only receive messages that are of interest, without knowledge of what (if any) publishers there are."

Note

This pattern enforces a natural loose coupling and provides more scalability than an engine that requires a tight connection between receivers and senders. In the first release of BizTalk Server, the product did have tightly coupled messaging components, but thankfully, the engine was completely redesigned for BizTalk Server 2004.

Once a message is received by a BizTalk adapter, it runs through any necessary preprocessing (such as decoding and validations) in BizTalk pipelines before being subjected to data transformation via BizTalk maps, and finally being published to a central database called the MessageBox. Then, the parties that have a corresponding subscription for that message can consume it as they see fit. While introducing a bit of unavoidable latency, the MessageBox database makes up for that by providing us with durability, reliability, and scalability. For instance, if one of our subscriber systems is offline for maintenance, outbound messages are not lost, but rather the MessageBox ensures that the messages are queued until the subscriber is ready to receive them. Worried about a large flood of inbound messages that steal processing threads away from other BizTalk activities? No problem! The MessageBox ensures that each and every message finds its way to its targeted subscriber, even if it must wait until the flood of inbound messages subsides.

There are really two ways to look at the way BizTalk is structured. The first is the traditional EAI view, which sees BizTalk receiving messages and routes them to the next system for consumption. The flow is very linear and BizTalk is seen as a broker between two applications, shown as follows:

However, the other way to consider BizTalk, and the focus of this book, is as a Service Bus, with numerous input/output channels that process messages in a very dynamic way. That is, instead of visualizing the data flow as a straight path through BizTalk to a destination system, consider BizTalk exposing services as on-ramps to a variety of destinations. Messages published to BizTalk Server may fan out to dozens of subscribers, who have no interest in what the publishing application actually was. Instead of thinking about BizTalk as a simple connector of systems, think of it as a message bus that coordinates a symphony of events between endpoints.

This concept is an exciting way to exploit BizTalk's engine in this modern world of service orientation. In the following figure, I've shown how the central BizTalk bus has receiver services hanging from it, and has a multitude of distinct subscriber services that are activated by relevant messages reaching the bus:

Note

If the on-ramp concept is a bit abstract to understand, consider a simple analogy. In designing the transportation for a city, it would be foolish to create distinct roads between each and every destination. The design and maintenance of such a project would be lunacy. It would be smart to design a shared highway with on and off ramps, which enable people to use a common route to get to the numerous locations around town. As new destinations in the city emerge, the entire highway (or road system) doesn't need to undergo changes, but rather, only a new entrance/exit point needs to be appended to the existing shared infrastructure.

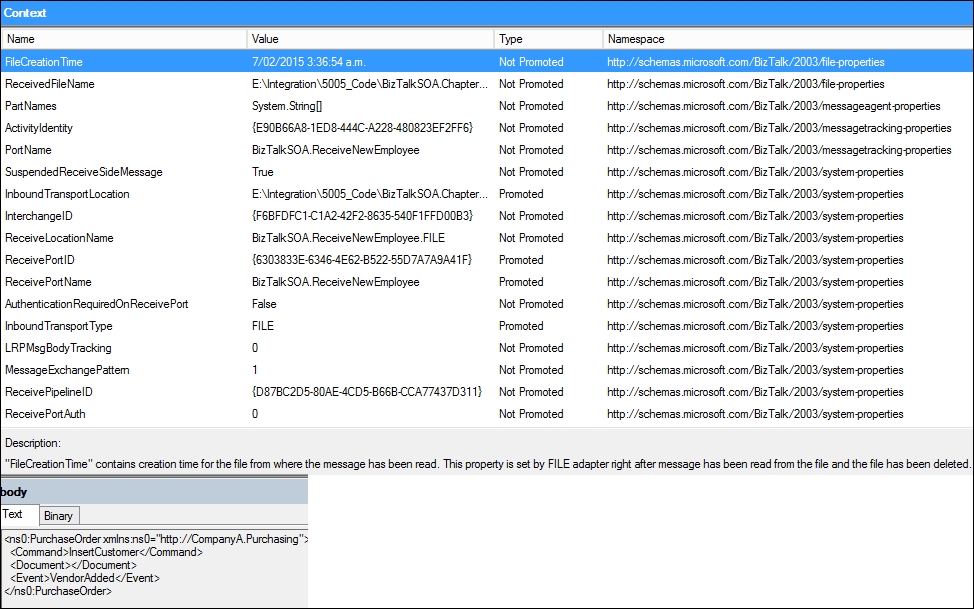

What exactly is a message anyway? A message is data processed through BizTalk Server's messaging engine, whether that data is transported as an XML document, a delimited flat file, or a Microsoft Word document. The message content may contain a command (for example, InsertCustomer), a document (for example, Invoice), or an event (for example, VendorAdded). A message has a set of properties associated with it. First and foremost, a message may have a type associated with it, which uniquely defines it within the messaging bus. The type is typically comprised of the XML namespace and the root node name (for example, http://CompanyA.Purchasing#PurchaseOrder). The message type is much like the class object in an object-oriented programming language; it uniquely identifies entities by their properties. The other critical attribute of a message in BizTalk Server is the property bag called the message context, as shown in the following screenshot:

The message context is a set of name/value properties that stay attached to the message as long as it remains within BizTalk Server. These context values include metadata about the transport used to publish the message and attributes of the message itself. Properties in the message context that are visible to the BizTalk engine, and therefore available for routing decisions, are called promoted properties.

How does a message actually get into BizTalk Server? A receive location is configured for the actual endpoint that receives messages. The receive location uses a particular adapter that knows how to absorb the inbound message. For instance, a receive location may be configured to use the FILE adapter, which polls a particular directory for XML messages. The receive location stores the file path to monitor, while the adapter provides transport connectivity. Upon receipt of a message, the adapter stamps a set of values into the message context. For the FILE adapter, values such as ReceivedFileName are added to that message's context property bag.

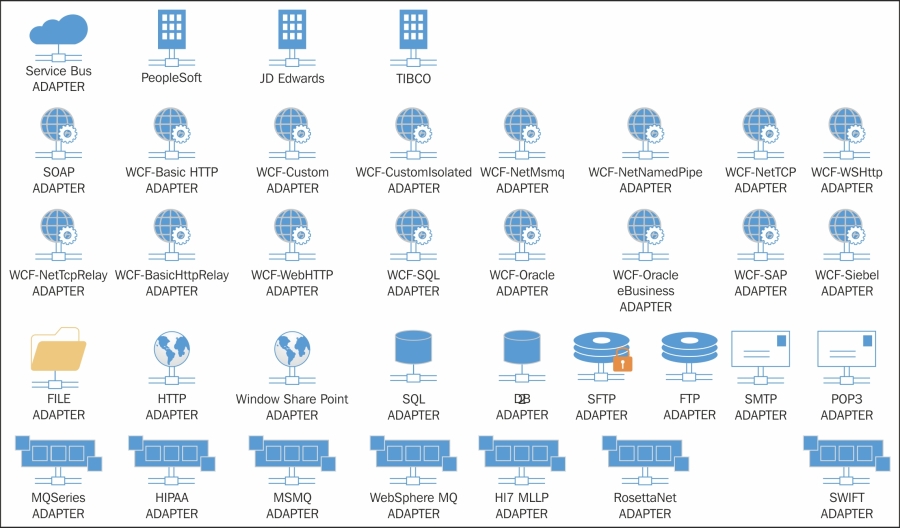

Note that BizTalk has both application adapters, such as SQL Server, Oracle, and SAP, as well as transport-level adapters, such as HTTP, MSMQ, and FILE. The key point is that the adapter configuration user experience is virtually identical regardless of the type of adapter chosen. Some of the adapters available are shown in the following figure:

Receive locations have a particular receive pipeline associated with them. A pipeline is a sequential set of optional operations that is performed on the message in preparation of being parsed and sent to the message box database by the BizTalk adapter. For instance, I would need a pipeline in order to decrypt, unzip, or validate the XML structure of my inbound message. One of the most critical roles of the pipeline is to identify the type of the inbound message and put the type into the message context as a promoted property. Custom pipelines can serve as preprocessing stages to make the message useful for processing. As discussed earlier, a message type is the unique characterization of a message. Think of a receive pipeline as performing all the preprocessing steps necessary for putting the message in to its most usable format.

A receive port contains one or more receive locations. Receive ports have XSLT maps associated with them that are applied to messages prior to publishing them to the MessageBox database. What value does a receive port offer? It acts as a grouping of receive locations where capabilities such as mapping and data tracking can be applied to all of the associated receive locations. It may also act as a container that allows us to publish a single entity to BizTalk Server regardless of how it came in, or what it looked like upon receipt. Let's say that my receive port contains three receive locations, which all receive slightly different "invoice" messages from three different external vendors. At the receive port level, I have three maps that take each unrelated message and maps it to a single, common format, before publishing it to BizTalk.

Now that we have a message cleaned up (by the pipeline) and in the final structure (via an XSLT map), it's published to the BizTalk Server MessageBox where message routing can begin. For our purposes, there are two types of subscribers that we care about. The first type of subscriber is a send port. A send port is conceptually the inverse of the receive location and is responsible for transporting messages out of the BizTalk "bus".

It has not only the adapter reference, adapter configuration settings, and pipeline (much like the receive location), but also the ability to apply XSLT maps to outbound messages. If a send port subscribes to a message, it first applies any XSLT map to the message, then processes it through a send pipeline, and finally uses the adapter to transmit the message out of BizTalk.

The other type of subscriber for a published message is a BizTalk orchestration. An orchestration is an executable business process that uses messages to complete operations in a workflow. We'll spend plenty of time working with orchestration subscribers throughout this book.