Authentication is one of two key security concepts that you must internalize when developing secure applications (the other being authorization). Authentication identifies who is attempting to request a resource. You may be familiar with authentication in your daily online and offline life, in very different contexts, as follows:

- Credential-based authentication: When you log in to your web-based email account, you most likely provide your username and password. The email provider matches your username with a known user in its database and verifies that your password matches what they have on record. These credentials are what the email system uses to validate that you are a valid user of the system. First, we'll use this type of authentication to secure sensitive areas of the JBCP calendar application. Technically speaking, the email system can check credentials not only in the database but anywhere, for example, a corporate directory server such as Microsoft Active Directory. A number of these types of integrations are covered throughout this book.

- Two-factor authentication: When you withdraw money from your bank's automated teller machine, you swipe your ID card and enter your personal identification number before you are allowed to retrieve cash or conduct other transactions. This type of authentication is similar to the username and password authentication, except that the username is encoded on the card's magnetic strip. The combination of the physical card and user-entered PIN allows the bank to ensure that you should have access to the account. The combination of a password and a physical device (your plastic ATM card) is a ubiquitous form of two-factor authentication. In a professional, security-conscious environment, it's common to see these types of devices in regular use for access to highly secure systems, especially dealing with finance or personally identifiable information. A hardware device, such as RSA SecurID, combines a time-based hardware device with server-based authentication software, making the environment extremely difficult to compromise.

- Hardware authentication: When you start your car in the morning, you slip your metal key into the ignition and turn it to get the car started. Although it may not feel similar to the other two examples, the correct match of the bumps on the key and the tumblers in the ignition switch function as a form of hardware authentication.

There are literally dozens of forms of authentication that can be applied to the problem of software and hardware security, each with their own pros and cons. We'll review some of these methods as they apply to Spring Security throughout the first half of this book. Our application lacks any type of authentication, which is why the audit included the risk of inadvertent privilege escalation.

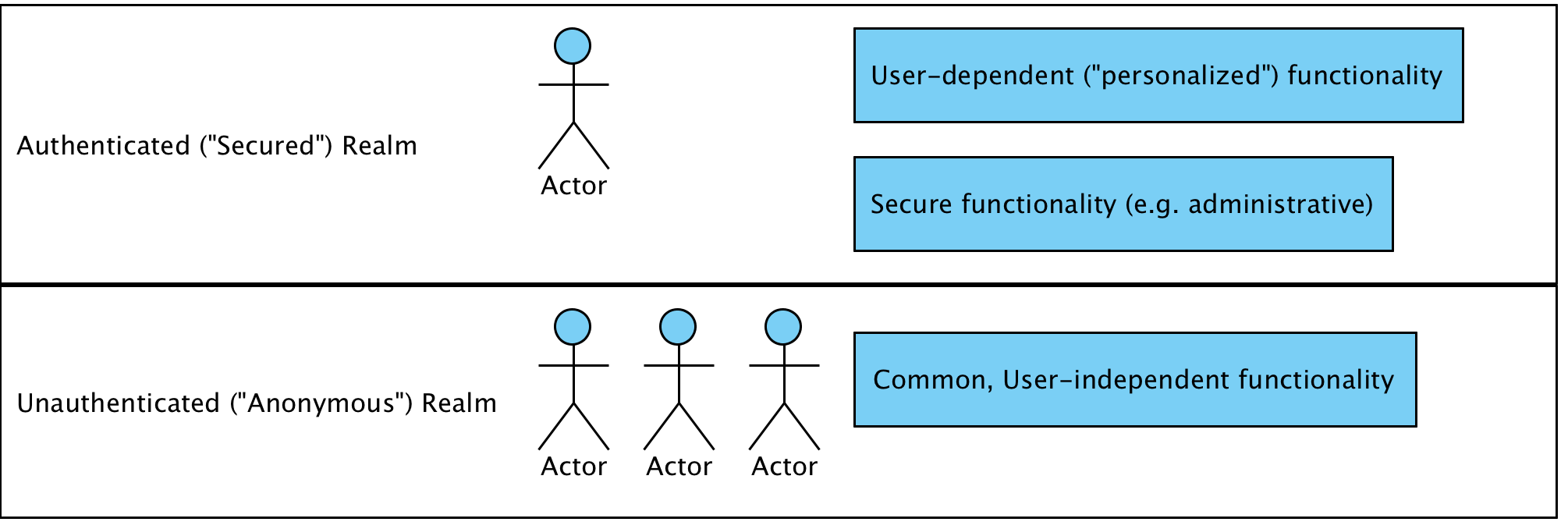

Typically, a software system will be divided into two high-level realms, such as unauthenticated (or anonymous) and authenticated, as shown in the following screenshot:

Application functionality in the anonymous realm is the functionality that is independent of a user's identity (think of a welcome page for an online application).

Anonymous areas do not do the following:

- Require a user to log in to the system or otherwise identify themselves to be usable

- Display sensitive information, such as names, addresses, credit cards, and orders

- Provide functionality to manipulate the overall state of the system or its data

Unauthenticated areas of the system are intended for use by everyone, even by users who we haven't specifically identified yet. However, it may be that additional functionality appears to identified users in these areas (for example, the ubiquitous Welcome {First Name} text). The selective displaying of content to authenticated users is fully supported through the use of the Spring Security tag library and is covered in Chapter 11, Fine-Grained Access Control.

We'll resolve this finding and implement form-based authentication using the automatic configuration capability of Spring Security in Chapter 2, Getting Started with Spring Security. Afterwards, we will explore various other means of performing authentication (which usually revolves around system integration with enterprise or other external authentication stores).