Why security is hard

In many organizations, implementing security is hard work. At a technical level, security is often seen as a blocker, at a tactical level, security considerations may change how the business operates, and at a strategic and political level, security often raises problems that many organizations prefer to ignore. This section will place security operations at the core of a security program and introduce the five types of cyber defense.

Security operations

This book takes the view that security operations are the heart of a security program. When organizations do their security operations well, they generate the necessary context to develop strategy, policies, and reporting, and gain the most benefit from audits.

The centrality of security operations is a somewhat unpopular view: much of what we see in security writing, focuses heavily on technology – which is the implementation side of security – or strategy, which focuses on the management and maturity of the program. By not considering security operations, the focus of too many organizations is still on prevention and controls. While prevention and controls are important, in this book I argue – based on experience – that they are the result of good security operations rather than the cause.

In a nutshell, security operations are an organization's capability to detect and respond to adversarial events on their systems and networks.

That is a mouthful, but we can unpack this a bit. Detection speaks to the capability of an organization to notice that something is wrong on their networks, preferably in an early stage of an attack, respond speaks to their capability to deal with such an event. Adversarial indicates that the event is caused by humans and has a specific component of intent.

In this book, I'll focus specifically on security operations and the ethos needed to create and sustain a security team that excels in security operations.

Therefore, I'll stay away from talking too much about either technology and strategy and instead focus heavily on tactics. Tactics – the specialty of security operations – is the nitty-gritty of how organizations respond to actual attacks, threats, vulnerabilities, and adversarial activity on their systems and networks.

If you think of strategy as the why of security, and the technology as the what, then tactics is the how – how do we realistically implement a risk program, how do we use that technology that has just been bought, and how do we secure an enterprise? These are the questions I will aim to answer in this book, and it is a critical connecting layer between technology and strategy that has not received the attention it deserves.

Cybersecurity, threats, and risk

Cybersecurity is traditionally approached from the viewpoint of business risk management. This creates a disconnect with security operations, and that fundamental disconnect makes security in many organizations harder than it needs to be.

To understand this better, we can look at how risk management usually approaches areas of risk. While the view of risk management I develop here is very simplified, it captures all the essentials. Risk management is typically based on a risk register, where risks are enumerated and given a priority of high, medium, or low (or a color-coded scale) based on both the exposure to the risk (the likelihood) and the impact (the consequence). In most cases, these assessments are subjective and dependent on the sector and context.

Risk management then relies on a matrix of controls to manage risk. Broadly speaking, risk treatment has four options: prevention, reduction, acceptance, or transfer. Prevention means that the organizations put in a device or measure that prevents the risk from materializing. Reduction means that some compensating control is developed that controls the risk, or at least make it visible in time.

Acceptance of risk means just that – the risk is accepted by the organization and no further action is undertaken to address it; consequences will have to be dealt with as they occur. This can happen, for instance, when a risk is too costly or cumbersome to address, or when the costs and effort associated with addressing it make no sense from the viewpoint of the risk accepted.

A transfer of risk occurs when the risks are borne by a third party, for instance in the case when an organization buys cyber insurance. We will have more to say on cyber insurance in Chapter 7, How Secure Are You? – Measuring Security Posture

Once this table is complete, risks are then prioritized, mitigations costed and budgeted, and the budgets for the highest risks are approved. Then it's rinse and repeat.

Measuring cybersecurity risk

While you might think that risk management is a typical business way of dealing with the risks posed by cybersecurity and is therefore easily understood by senior leaders in an organization, you would be wrong. In How to Measure Anything in Cybersecurity Risk, Wiley, 2016, Douglas Hubbard and Richard Seiersen argue passionately and in depth that this method of dealing with risk is a failure and does not work. While cybersecurity is indeed a business risk, we need to come up with a better method to communicate and treat risk. In Chapter 7, How Secure Are You? – Measuring Security Posture, we will return to the topic of how to make security relevant in a business context based on the model of security operations.

Security operations do not work this way. Security operations focus primarily on dealing with issues as they occur – that is, they focus on the here and now. Beyond the here and now, they focus on threats in the context of the business, and devise methods of detecting those threats.

To better understand the depth of the chasm that opens in this way, it helps to have a clear understanding of how organizations deal with cyber risk. Dealing with cyber risk from the perspective of a risk management framework leads an organization to put in passive defenses: things such as firewalls, antivirus, network controls, and access lists to form a defense in depth architecture. At worst, a strong focus on traditional risk can cause misspending on silver bullets: expensive security solutions that generally do much less than they promise, sometimes because the environment is not mature enough to make the most of the investment. Except for the silver bullet, passive defenses are all necessary in credible cyber defense, but they overlook large areas that organizations should also address when considering cyber defense.

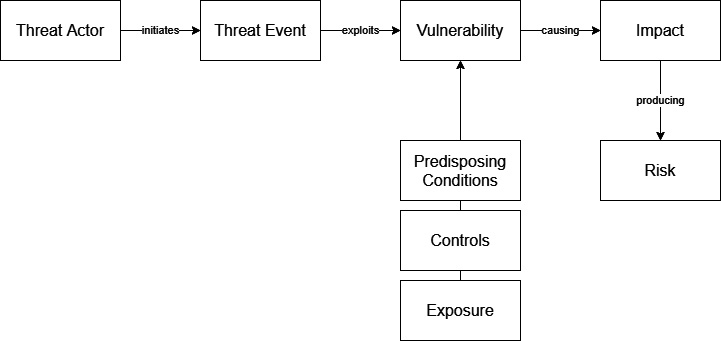

Figure 1.1 shows a risk treatment approach to threats that is often used in cybersecurity. Where a threat is identified, it is usually translated into risk, and then the risk treatment process defines whether a vulnerability exists and what the extent of it is (sometimes called the attack surface). Several controls look at how to reduce exposure, how to mitigate it (for example, by timely patching), and arrive at a residual risk that can be put on the heat map, or further reduced:

Figure 1.1 – Risk treatment of threats

This approach to threats focuses on passive defense. Thereby it misses out on important additional components of cybersecurity defense. Specifically, it misses out on what organizations may do (and, in my view, should do) in the areas of architecture, passive defense, active defense, intelligence, and perhaps even offense. These together make up the five types of cyber defense, which we discuss next.

Five types of cyber defense

As Rob Lee points out in The Sliding Scale of Cyber Security (2015) (https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/ActiveDefense/sliding-scale-cyber-security-36240), passive defense is only one of the five available modes of defense that organizations should consider when designing a cyber risk program. The five options sit on a spectrum, ranging from architecture, through passive defense to active defense, intelligence, and offense.

This spectrum can be read as follows:

- Architecture focuses on the design of systems so that they are as secure as possible. As part of architecture, we consider possible threats to the system and how the system can be made resilient against those threats. One of the most important aspects of architecture is threat modeling. We will discuss architecture in Chapter 5, Defensible Architecture.

- Passive defense focuses on the defense in depth and control framework that implements several systems (such as firewalls). These systems are added as preventive capabilities to the architecture to ensure that the system is robust against common attacks without constant human intervention. Packet Filters, for instance, allow traffic on ports and/or protocols only and will drop any packet that does not conform to its rules without human intervention.

- Active defense focuses specifically on threats and their contexts as they manifest themselves to us as defenders and is one of the key activities of agile security operations. Active defenders pick up what passive defenses miss. Active defense builds and maintains context and focus on active threats, based on a superior understanding of the environment. We will return to active defense in Chapter 6, Active Defense.

- Intelligence is the knowledge that an organization has about the tactics, techniques, and procedures of its adversaries. We will return to intelligence in Chapter 10, Implementing Agile Threat Intelligence.

- Offense focuses on the legal actions that a defender can take to disrupt or degrade an attacker's infrastructure. This may, for instance, include takedown actions where an attacker's infrastructure is removed from the internet by an authorized body.

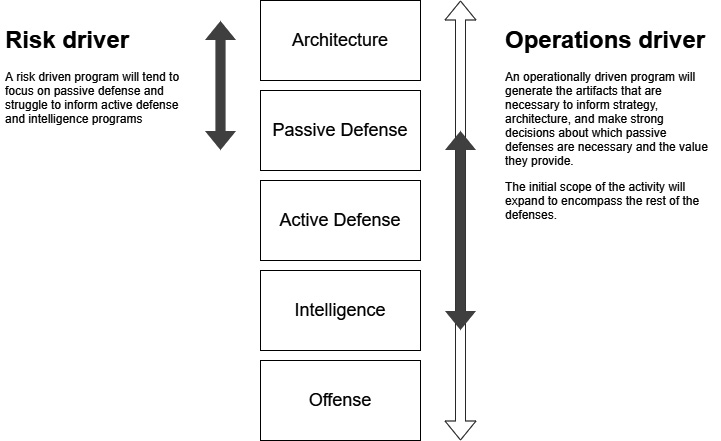

Figure 1.2 gives a representation of the five defense modes and the respective focus of risk-driven and operations-driven security programs. Well-managed operationally driven programs will tend to expand to encompass the five modes of defense, whereas risk-driven programs will tend to focus on architecture and passive defense:

Figure 1.2 – A representation of the five defense modes and the respective focus of risk-driven and operations-driven security programs

Risk management and security operations therefore operate from radically differing but also complementing perspectives and assumptions about how to best secure an organization.

This book is written from the conviction that starting with security operations, security risk management can be done much better than is usually the case. An operationally driven program changes the conversation from driving down an externally defined program to a fact-based discussion on what happens in this business.

It is, from that perspective, surprising that many organizations that do have extensive security programs and policy frameworks are weak when it comes to security operations.

The security 1%

In an interesting blog post (https://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2020/10/security-and-one-percent-thought.html), Richard Bejtlich points out that the people having somewhat credible detection and response capability form part of the security 1%. He focuses on membership in first.org and then performs a quick estimate of the percentage of organizations that would be able to mount a credible defense when they are attacked. The conclusion is that only around 1% of organizations would have detection and response capabilities and are not running just planning and resistance/prevention functions. While this is a back-of-the-envelope calculation, it does underscore the need to improve security operations across the board. The problem of the security 1% also leads to several other problems, especially the question of whether advanced penetration testing tools and IOCs should be made as widely available as they are: they are nearly useless to the security 99% but may lead to improvements in the capability of attackers, making the overall security situation worse.

The focus on security operations does not mean that governance, risk, and compliance are unimportant. The main takeaway from this section is that the focus on security operations as a central activity alters the point where organizations should start first: governance, risk, and compliance is not a strong starting point for a security program in the initial stage – it is better to focus on developing operations that inform the governance program, and develop the governance, risk, and compliance program from what the security operations discover.

All the preceding points hinge on the assumption that an operations-driven security program is managed well. In Chapter 7, How Secure Are You? – Measuring Security Posture, we will return to the topic of governance, risk, and compliance in detail, and outline how a well-managed program can base itself on its operations.