The ASP.NET Core revolution

To summarize what has happened in the ASP.NET world within the last decade is not an easy task; in short, we can say that we’ve undoubtedly witnessed the most important series of changes in .NET Framework since the year it came to life. This was a revolution that changed the whole Microsoft approach to software development in almost every way. To properly understand what happened in those years, it would be useful to identify some distinctive key frames within a slow, yet constant, journey that allowed a company known (and somewhat loathed) for its proprietary software, licenses, and patents to become a driving force for open source development worldwide.

The first relevant step, at least in my humble opinion, was taken on April 3, 2014, at the annual Microsoft Build conference, which took place at the Moscone Center (West) in San Francisco. It was there, during a memorable keynote speech, that Anders Hejlsberg – father of Delphi and lead architect of C# – publicly released the first version of the .NET Compiler Platform, known as Roslyn, as an open source project.

It was also there that Scott Guthrie, executive vice president of the Microsoft Cloud and AI group, announced the official launch of the .NET Foundation, a non-profit organization aimed at improving open source software development and collaborative work within the .NET ecosystem.

From that pivotal day, the .NET development team published a constant flow of Microsoft open source projects on the GitHub platform, including Entity Framework Core (May 2014), TypeScript (October 2014), .NET Core (October 2014), CoreFX (November 2014), CoreCLR and RyuJIT (January 2015), MSBuild (March 2015), the .NET Core CLI (October 2015), Visual Studio Code (November 2015), .NET Standard (September 2016), and so on.

ASP.NET Core 1.x

The most important achievement brought by these efforts toward open source development was the public release of ASP.NET Core 1.0, which came out in Q3 2016. It was a complete reimplementation of the ASP.NET framework that we had known since January 2002 and that had evolved, without significant changes in its core architecture, up to version 4.6.2 (August 2016). The brand-new framework united all the previous web application technologies, such as MVC, Web API, and web pages, into a single programming module, formerly known as MVC6. The new framework introduced a fully featured, cross-platform component, also known as .NET Core, shipped with the whole set of open source tools mentioned previously, namely, a compiler platform (Roslyn), a cross-platform runtime (CoreCLR), and an improved x64 Just-In-Time compiler (RyuJIT).

Some of you might remember that ASP.NET Core was originally called ASP.NET 5. As a matter of fact, ASP.NET 5 was no less than the original name of ASP.NET Core until mid-2016, when the Microsoft developer team chose to rename it to emphasize the fact that it was a complete rewrite. The reasons for that, along with the Microsoft vision about the new product, are further explained in the following Scott Hanselman blog post that anticipated the changes on January 16, 2016: http://www.hanselman.com/blog/ASPNET5IsDeadIntroducingASPNETCore10AndNETCore10.aspx.

For those who don’t know, Scott Hanselman has been the outreach and community manager for .NET/ASP.NET/IIS/Azure and Visual Studio since 2007. Additional information regarding the perspective switch is also available in the following article by Jeffrey T. Fritz, program manager for Microsoft and a NuGet team leader: https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/webdev/2016/02/01/an-update-on-asp-net-core-and-net-core/.

As for Web API 2, it was a dedicated framework for building HTTP services that returned pure JSON or XML data instead of web pages. Initially born as an alternative to the MVC platform, it has been merged with the latter into the new, general-purpose web application framework known as MVC6, which is now shipped as a separate module of ASP.NET Core.

The 1.0 final release was shortly followed by ASP.NET Core 1.1 (Q4 2016), which brought some new features and performance enhancements, and also addressed many bugs and compatibility issues affecting the earlier release.

These new features include the ability to configure middleware as filters (by adding them to the MVC pipeline rather than the HTTP request pipeline); a built-in, host-independent URL rewrite module, made available through the dedicated Microsoft.AspNetCore.Rewrite NuGet package; view components as tag helpers; view compilation at runtime instead of on-demand; .NET native compression and caching middleware modules; and so on.

For a detailed list of all the new features, improvements, and bug fixes in ASP.NET Core 1.1, check out the following links:

ASP.NET Core 2.x

Another major step was taken with ASP.NET Core 2.0, which came out in Q2 2017 as a preview and then in Q3 2017 for the final release. The new version featured a wide number of significant interface improvements, mostly aimed at standardizing the shared APIs among .NET Framework, .NET Core, and .NET Standard to make them backward-compatible with .NET Framework. Thanks to these efforts, moving existing .NET Framework projects to .NET Core and/or .NET Standard became a lot easier than before, giving many traditional developers a chance to try and adapt to the new paradigm without losing their existing know-how.

Again, the major version was shortly followed by an improved and refined one: ASP.NET Core 2.1. This was officially released on May 30, 2018, and introduced a series of additional security and performance improvements, as well as a bunch of new features, including SignalR, an open source library that simplifies adding real-time web functionality to .NET Core apps; Razor class libraries; a significant improvement in the Razor SDK that allows developers to build views and pages into reusable class libraries, and/or library projects that could be shipped as NuGet packages; the Identity UI library and scaffolding, to add identity to any app and customize it to meet your needs; HTTPS support enabled by default; built-in General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) support using privacy-oriented APIs and templates that give users control over their personal data and cookie consent; updated SPA templates for Angular and ReactJS client-side frameworks; and much more.

For a detailed list of all the new features, improvements, and bug fixes in ASP.NET Core 2.1, check out the following links:

Wait a minute: did we just say Angular? Yeah, that’s right. As a matter of fact, since its initial release, ASP.NET Core has been specifically designed to seamlessly integrate with popular client-side frameworks such as ReactJS and Angular. It is precisely for this reason that books such as this exist. The major difference introduced in ASP.NET Core 2.1 is that the default Angular and ReactJS templates have been updated to use the standard project structures and build systems for each framework (the Angular CLI and NPX’s create-react-app command) instead of relying on task runners such as Grunt or Gulp, module builders such as webpack, or toolchains such as Babel, which were widely used in the past, although they were quite difficult to install and configure.

Being able to eliminate the need for these tools was a major achievement, which has played a decisive role in revamping the .NET Core usage and growth rate among the developer communities since 2017. If you take a look at the two previous installments of this book – ASP.NET Core and Angular 2, published in mid-2016, and ASP.NET Core 2 and Angular 5, out in late 2017 – and compare their first chapter with this one, you will see the huge difference between having to manually use Gulp, Grunt, or webpack, and relying on the integrated framework-native tools. This is a substantial reduction in complexity that would greatly benefit any developer, especially those less accustomed to working with those tools.

Six months after the release of the 2.1 version, the .NET Foundation came out with a further improvement: ASP.NET Core 2.2 was released on December 4, 2018, with several fixes and new features, including an improved endpoint routing system for better dispatching of requests, updated templates featuring Bootstrap 4 and Angular 6 support, and a new health checks service to monitor the status of deployment environments and their underlying infrastructures, including container orchestration systems such as Kubernetes, built-in HTTP/2 support in Kestrel, and a new SignalR Java client to ease the usage of SignalR within Android apps.

For a detailed list of all the new features, improvements, and bug fixes in ASP.NET Core 2.2, check out the following links:

ASP.NET Core 3.x

ASP.NET Core 3 was released in September 2019 and came with another bunch of performance and security improvements and new features, such as Windows desktop application support (Windows only) with advanced importing capabilities for Windows Forms and Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) applications; C# 8 support; .NET Platform-dependent intrinsic access through a new set of built-in APIs that could bring significant performance improvements in certain scenarios; single-file executable support via the dotnet publish command using the <PublishSingleFile> XML element in project configuration or through the /p:PublishSingleFile command-line parameter; new built-in JSON support featuring high performance and low allocation that’s arguably two to three times faster than the JSON.NET third-party library (which became a de facto standard in most ASP.NET web projects); TLS 1.3 and OpenSSL 1.1.1 support in Linux; some important security improvements in the System.Security.Cryptography namespace, including AES-GCM and AES-CCM cipher support; and so on.

A lot of work has also been done to improve the performance and reliability of the framework when used in a containerized environment. The ASP.NET Core development team put a lot of effort into improving the .NET Core Docker experience on .NET Core 3.0. More specifically, this is the first release featuring substantive runtime changes to make CoreCLR more efficient, honor Docker resource limits better (such as memory and CPU) by default, and offer more configuration tweaks. Among the various improvements, we could mention improved memory and GC heap usage by default, and PowerShell Core, a cross-platform version of the famous automation and configuration tool, which is now shipped with the .NET Core SDK Docker container images.

.NET Core 3 also introduced Blazor, a free and open source web framework that enables developers to create web apps using C# and HTML.

Last but not least, it’s worth noting that the new .NET Core SDK is much smaller than the previous installments, mostly thanks to the fact that the development team removed a huge set of unnecessary artifacts included in the various NuGet packages that were used to assemble the previous SDKs (including ASP.NET Core 2.2) from the final build. The size improvements are huge for Linux and macOS versions, while less noticeable on Windows because that SDK also contains the new WPF and Windows Forms set of platform-specific libraries.

For a detailed list of all the new features, improvements, and bug fixes in ASP.NET Core 3.0, check out the following links:

- Release notes: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/core/whats-new/dotnet-core-3-0

- ASP.NET Core 3.0 releases page: https://github.com/dotnet/core/tree/master/release-notes/3.0

ASP.NET Core 3.1, which is the most recent stable version at the time of writing, was released on December 3, 2019.

The changes in the latest version are mostly focused on Windows desktop development, with the definitive removal of a number of legacy Windows Forms controls (DataGrid, ToolBar, ContextMenu, Menu, MainMenu, and MenuItem) and added support for creating C++/CLI components (on Windows only).

Most of the ASP.NET Core updates were fixes related to Blazor, such as preventing default actions for events and stopping event propagation in Blazor apps, partial class support for Razor components, and additional Tag Helper Component features; however, much like the other .1 releases, the primary goal of .NET Core 3.1 was to refine and improve the features already delivered in the previous version, with more than 150 performance and stability issues fixed.

A detailed list of the new features, improvements, and bug fixes introduced with ASP.NET Core 3.1 is available at the following URL:

.NET 5

Just when everyone thought that Microsoft had finally taken a clear path with the naming convention of its upcoming frameworks, the Microsoft developer community was shaken again on May 6, 2019, by the following post by Richard Lander, Program Manager of the .NET team, which appeared on the Microsoft Developer Blog: https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/introducing-net-5/.

The post got an immediate backup from another article that came out the same day written by Scott Hunter, Program Management Director of the .NET ecosystem: https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/net-core-is-the-future-of-net/.

The two posts were meant to share the same big news to the readers: .NET Framework 4.x and .NET Core 3.x would converge in the next major installment of .NET Core, which would skip a major version number to properly encapsulate both installments.

The new unified platform would be called .NET 5 and would include everything that had been released so far with uniform capabilities and behaviors: .NET Runtime, JIT, AOT, GC, BCL (Base Class Library), C#, VB.NET, F#, ASP.NET, Entity Framework, ML.NET, WinForms, WPF, and Xamarin.

Microsoft said they wanted to eventually drop the term “Core” from the framework name because .NET 5 would be the main implementation of .NET going forward, thus replacing .NET Framework and .NET Core; however, for the time being, the ASP.NET Core ecosystem is still retaining the name “Core” to avoid confusing it with ASP.NET MVC 5; Entity Framework Core will also keep the name “Core” to avoid confusing it with Entity Framework 5 and 6. For all of these reasons, in this book, we’ll keep using “ASP.NET Core” (or .NET Core) and “Entity Framework Core” (or “EF Core”) as well.

From Microsoft’s point of view, the reasons behind this bold choice were rather obvious:

- Produce a single .NET runtime and framework that can be used everywhere and that has uniform runtime behaviors and developer experiences

- Expand the capabilities of .NET by taking the best of .NET Core, .NET Framework, Xamarin, and Mono

- Build that product out of a single code base that internal (Microsoft) and external (community) developers can work on and expand together and that improves all scenarios

The new name could reasonably generate some confusion among those developers who still remember the short timeframe (early to mid-2016) in which ASP.NET Core v1 was still called ASP.NET 5 before its final release. Luckily enough, that “working title” was ditched by the Microsoft developer team and the .NET community before it could leave noticeable traces on the web.

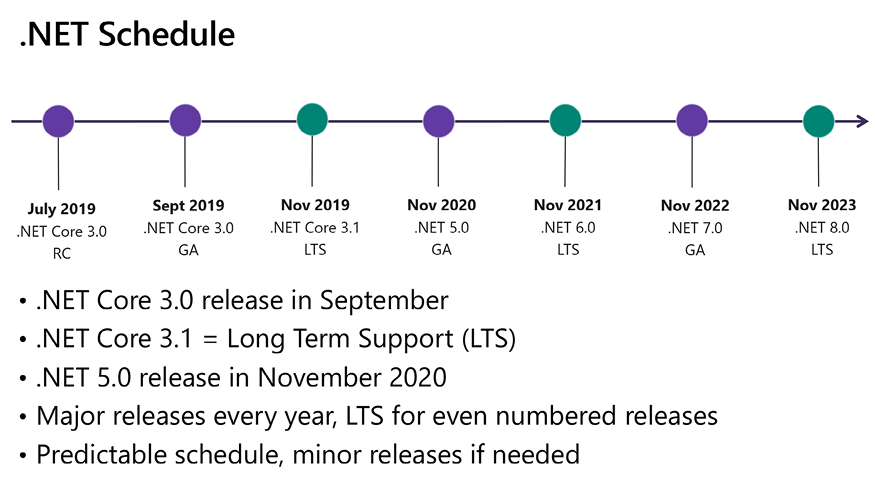

.NET 5 was released on General Availability in November 2020, a couple of months after its first Release Candidate, thus respecting the updated .NET schedule that aims to ship a new major version of .NET once a year, every November:

Figure 1.1: .NET schedule

In addition to the new name, the .NET 5 framework brought a lot of interesting changes, such as:

- Performance improvements and measurement tools, summarized in this great analysis performed by Stephen Toub (.NET Partner Software Engineer) using the new Benchmark.NET tools: https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/performance-improvements-in-net-5/.

- Half Type, a binary floating point that occupies only 16 bits and that can help to save a good amount of storage space where the computed result does not need to be stored with full precision. For additional info, take a look at this post by Prashanth Govindarajan (Senior Engineering Manager at LinkedIn): https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/introducing-the-half-type/.

- Assembly trimming, a compiler-level option to trim unused assemblies as part of publishing self-contained applications when using the self-contained deployment option, as explained by Sam Spencer (.NET Core team Program Manager) in this post: https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/app-trimming-in-net-5/.

- Various improvements in the new System.Text.Json API, including the ability to ignore default values for value-type properties when serializing (for better serialization performance) and to better deal with circular references.

- C# 9 and F# 5 language support, with a bunch of new features such as Init Only Setters (that allows the creation of immutable objects), function pointers, static anonymous functions, target-typed conditional expressions, covariant return types, and module initializers.

And a lot of other new features and improvements besides.

A detailed list of the new features and improvements and a comprehensive explanation of the reasons behind the release of ASP.NET 5 are available at the following URL:

- Release notes: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/core/dotnet-five

- For additional info about the C# 9.0 new features, take a look at the following URL: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/whats-new/csharp-9.

.NET 6

.NET 6 came out on November 8, 2021, a year after .NET 5, as expected by the .NET schedule. The most notable improvement in this version is the introduction of the Multi-platform Application UI, also known as MAUI: a modern UI toolkit built on top of Xamarin, specifically created to eventually replace Xamarin and become the .NET standard for creating multi-platform applications that can run on Android, iOS, macOS, and Windows from a single code base.

The main difference between MAUI and Xamarin is that the new approach now ships as a core workload, shares the same base class library as other workloads (such as Blazor), and adopts the most recent SDK Style project system introduced with .NET 5, thus allowing a consistent tooling and coding experience for all .NET developers.

In addition to MAUI, .NET 6 brings a lot of new features and improvements, such as:

- C# 10 language support, with some new features such as null parameter checking, required properties, field keyword, file-scoped namespaces, top-level statements, async main, target-typed new expressions, and more.

- Implicit using directives, a feature that instructs the compiler to automatically import a set of

usingstatements based on the project type, without the need to explicitly include them in each file. - New project templates, which are much cleaner and simpler since they do implement (and demonstrate) most of the language improvements brought by C# version 9 and 10 (including those we’ve just mentioned).

- Package Validation tooling, an option that allows developers to validate that their packages are consistent and well-formed during package development.

- SDK workloads, a feature that leverages the concepts of “workloads” introduced with .NET Core to allow developers to install only necessary SDK components, skipping the parts they don’t need: in other words, it’s basically a “package manager” for the SDKs.

- Inner-loop performance improvements, a family of tweaks dedicated to the performance optimization of the various tools and workflows used by developers (such as CLI, runtime, and MSBuild), thereby aiming to improve their coding and building experience. The most important of them is the Hot Reload, a feature that allows the project’s source code to be modified while the application is running, without the need to manually pause or hit a breakpoint.

For a comprehensive list of the new C# 10 features, check out the following URL: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/whats-new/csharp-10.

This concludes our journey through the recent history of ASP.NET. In the next section, we’ll move our focus to the Angular ecosystem, which experienced a rather similar turn of events.