Chapter 3. Query Manager and Query Statements

In the previous chapter, you learned about two basic tools, Query Generator and Query Wizard. Meanwhile, you also learned about system queries so that you can create or use queries with these tools. However, those tools have certain limitations.

The most inconvenient limitation is that only a fixed set of tables is available to you with these tools. For example, the table list does not show all tables in the database. When the queries become complicated, these tools may not work for you.

You must be eager to know how to create queries freely without those restrictions. Do you have other ways of creating queries when you need to create them in complex logic? The answer is definitely: "Yes". This is the topic of this chapter.

This chapter illustrates the most important business intelligence tool for SAP Business One: Query Manager. You will learn how to manage your queries by creating, saving, and deleting them directly from the Query Manager. At the same time, you will learn how to organize your queries into categories. The detailed query statements, keywords, and functions will be presented to you as well.

In the first section, you will learn everything related to the Query Manager such as User Interface, including each button. The query categories for saved query will also be discussed. The next section will show you the most commonly used basic statements for queries one by one. All statements are fully explained. They cover the most frequently used statements. The last section covers the query functions, including the most commonly used functions or expressions.

Query manager user interface

The following screenshot shows you how to access this tool from the SAP Business One menu:

Just like the other query tools, Query Manager can be accessed through the first menu item under Tools | Queries.

You can also access it directly from the toolbar. The Query Manager icon can be found on the toolbar between the Form Settings and Message/Alert icons. This icon is shown in the previous screenshot on the left side of Query Manager.

In the Query Manager window, you can:

- Display all existing queries

- Create and save user queries

- Delete user queries

- Manage query categories

Query Manager is used for query management. All queries can be saved, edited, or deleted by using the Query Manager tool. It does not matter if the query is created by tools like Query Generator/Query Wizard, or by users directly from the query result windows.

Display all existing queries

This is the simplest function for the Query Manager. You can find all your saved queries or system queries through the Query Manager User interface.

The first text block on the top of the Query Manager can display the query name you have selected or allow you to type a query name for a new query before you save it.

The next text block below the query name can display the query category you have selected or allow you to type a query category name for a new query category before you save it through the Manage Category function.

The big window under these two boxes is the place to display all query categories and the query names for the expanded categories you have selected.

The first screenshot shows the system query names:

The second example shows the query categories plus the query names under expanded query categories:

You may notice that there are two different icons in front of each query category: the Down Arrow icon next to the General category and the Right Arrow icon next to System as well as other categories. The Down Arrow icons stand for the query categories that are expanded to display the query names under the categories. The Right Arrow icons refer to the query categories that are not expanded. When you click on the icon, the status will change from expanded to non-expanded or vice versa. To find a query under a specific category, you just need to click on the icon in front of the query category to expand it.

You can display any queries in two ways:

- The first way is from the Query Manager window directly. You can find the required query name and double-click on the name or you can click OK when you select a specific query name. The selected query will be displayed on the query result window with either method.

- The second way is bypassing the Query Manager window. You can also find the query name directly from Tools | Queries | User Queries. One click is good enough to bring up the query result window with this method.

The second method presents a limitation. If the query name is too long, it might be cut off when you display their names directly from the Tools menu. Or if you have special characters, it may not display them fully either. It is advisable to use shorter names for queries whenever possible. Avoid using special characters whenever possible.

Tip

When you name a query, it is better not to name them similar to each other. You may have the misfortune wherein, all names are not easily distinguishable if the first 40 characters are the same.

Creating and saving user queries

Creating user queries can be done directly after you run any queries in order to bring up the query result window. The query you want to run can either be from query tools directly or selected from the Query Manager.

When you open the query result window by either of the methods mentioned earlier, you might be able to edit or create a query from scratch, if you have the right authorization. In case you don't have the user privilege, check with the Superuser in your company.

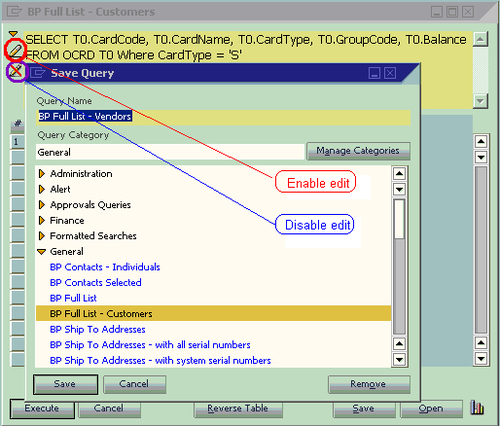

Once you have got proper user rights, you will be able to find two icons on the left screen beside the query script. They look like a pencil or a pencil with a red line cross. From the previous screenshot, you can find that the first icon is used for enabling edit queries and the second icon is the opposite, that is, to disable the editing ability. When you click on the pencil icon, you will have the power to write any queries to retrieve data from any tables in the database.

Unlike the other query tools, you have to write every single statement, keyword, column name, table name, function, and parameter on your own. The freedom to write query as you wish requires that you have both high level SQL query knowledge and SAP Business One database structure knowledge. If you find it is difficult, you need to go back to the previous chapter. Spend your time with the tools until you are ready.

To save your query, you just need to follow these steps:

- Click on Save. The Save Query window will show up.

- Select any categories from the list.

- Type in a proper query name.

- Click on Save under the bottom of the window.

Your query will be saved immediately with the previously mentioned steps.

The Save Query window is similar to the Query Manager window. Any query categories or query names displayed in the Query Manager window, will be displayed in the Save Query window too.

The following example shows that the existing query, BP Full List—Customer, has been edited. The new query can be saved by selecting the category General and selecting a query name to modify it to. The new name BP Full List—Vendors has been entered. After clicking on Save, this new query is saved under the General category. You can just type in the name if the name is not very long.

Note

Warning: Although you can write some DML queries such as UPDATE, DELETE, or INSERT in the query result windows, those DML queries have to be restricted to only your User Defined Tables (UDT). Even User Defined Field (UDF) in the system tables is not allowed to be updated by the SQL Query directly. You face great risk of losing your SAP support in case of any corruptions in your database, if you have directly updated system tables.

If you need to create a query from scratch without bringing up other queries, you can create an empty query such as SELECT '' and save it by a name Blank or Empty. If you run this query, you will see nothing in the query result but empty space that allows you to create a brand new query.

It is simple to delete a user query. You don't need to open the query to run it, but delete it from the Query Manager window directly. After you have selected the Query Manager from the menu or through the icon, you can select the query you want to delete. Click on the Remove button, and a warning message will popup to confirm that you want to delete the query. If you have not reached this point through a wrong mouse click, you can click on Yes to proceed. The query will be deleted from the database.

There is an alternative way to delete queries. That is to bring up the Save Query window by clicking Save under the query result window. Instead of saving queries, you may select any user queries to delete. Clicking on the Remove button is all you need to do.

After deleting queries, you can click on Cancel to return to the query result window.

Note

Be careful when you delete your query. There is no Undo function like some other applications. Once the query is deleted, there is no way to retrieve it unless you restore your entire database! A practical remedy is to copy and save all queries to a text document after you have created them. It will save you time whenever you find the queries have to be revised or deleted.

Managing query categories

Categories are the folders for queries. They include categories for system queries and categories for user queries. You always get a default category called General when you have a new database. There is nothing else beside these system and general categories in the beginning. It is dependent on an administration user to create and maintain your queries with any categories you like.

If you only have few queries, categories may not be that important to you. However, this will change as soon as you have more saved queries. Good category management can save you tremendous time. You can maintain the categories with the same structure as the SAP Business One menu system. Any queries can be found quickly in this way.

Categories are similar to directories or folders in an operating system, with one exception. This is not a trivial exception. There is only one level for categories under the Query Manager. You don't have the option to create multi-level categories.

Tip

Due to the limitations of having only one level category, your plan to create categories should avoid any overlap structure. If your categories have not clearly divided the scope of your queries, you may face a dilemma in saving your new query to a proper category. When you try to find the saved queries in the future, it may actually increase your troubles in getting the right queries, instead of saving you time.

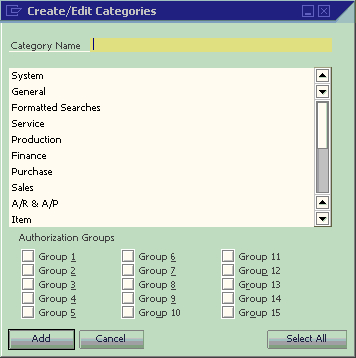

To manage categories, you can click Manage Category beside the second text box. After you click the button, a window with a title Create/Edit Categories will pop up like in the following screenshot:

When this window pops up, it is always in Add mode. You can add a new category by typing any letters in the text box close to the top of window. Then click ADD. The new category will be added right away.

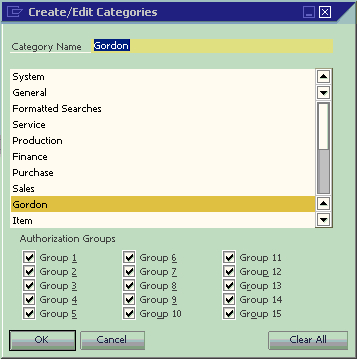

If you are not satisfied with the category name, it is very easy to edit it. Just select a category name when you are in the Add mode. The Add button will change to an Update button instantly, like the example in the following screenshot. A/R & A/P category is selected to be a candidate for update.

Note

User rights for category maintenance should be left to the person who has full administration right. Only Superusers must handle this function. Detailed discussion can be found in Chapter 5 for query security.

You can type in your preferred category name at this time. In the example, Gordon is typed in. When you click Update, the category name changes to Gordon instead of A/R &

A/P.

The query names under the same category will not be affected when you are editing category names. Actually, this is the category ID to be used by the system. This category ID is not changed during your category name update.

After you click Update, the window is changed to find mode. The button is changed again from Update to OK. You can still select any categories just like in the Add mode. However, the button will not change to Update this time. It still shows OK.

To add another new category, you have to change the window mode to Add mode. This can be done through the menu item Data | Add, keyboard shortcut

Ctrl+A or the icon on the toolbar.

The last button to be discussed is the Select All button. This button allows you to select all Authorization Groups. If you want to assign your query category to more than half of the authorization groups, it will be easier to click on this button first. Then you can deselect any groups. If you just assign to less than half of the groups, you can check them one by one. It will save you time compared with unchecking many boxes after Select All.

Whenever you have not selected all groups, the Select All button will be available. As soon as all groups are selected, the button will change to Clear All. The authorization groups are used for query report user authorizations. The details for query report user authorizations will be discussed in Chapter 5.

SQL queries comprise a statement, keyword, function, expression, and parameters. To see how commonly used query statements work, you can have a look at the following query example that includes most of the statements and some of the functions. The query contents and meaning of these query results will be discussed in the next chapter:

This query can be used to return the top five customers for sales in any period based on the date range you selected. It includes most of the statements that are going to be discussed in this chapter.

Let us go through those statements or functions in Bold from the sample query one by one:

SELECT—first statement to retrieve data

It is quite obvious from the meaning of the word that SELECT is used to display or retrieve data from certain data sources.

The SELECT statement is used to return data from a set of values or database tables.

The result is stored in a result table, called the result-set.

SELECT is one of the most commonly used Data Manipulation Language (DML) commands. It seems very simple. However, something important needs to be explained for this statement:

- The scope of the value that can be retrieved

- The numbers of columns to be included

- Column name descriptions

- Keywords followed to this statement

The scope of the value that can be retrieved

Here is a return value list that SELECT can be used for:

- A single value

- A group of values

- Return a single database table column

- Return a group of database table columns

- Return complete database table columns

- Used in a subquery

The simplest SELECT query would be just to get a constant or text without any additional statements. An example would be:

These queries will display Yes or 10 in one column when executed.

You may also use this statement to get a group of values. For example:

This query will display Yes, 10, This is an example in three columns named Yes/No, No., and Content when you execute it.

Some special uses of this statement to display a single value or group of values will be discussed in other chapters when we introduce more specific topics.

Please note the comma used above. Following the SELECT statement, each comma will define a new column to be displayed.

Tip

Do not forget to delete the last comma in a SELECT statement. This simple mistake is one of the most frequent problems for a query. It is mainly due to the fact that we are often used to copying columns in our queries, which include the comma, and forget to remove the last one before testing the query.

Return a single database table column

Similar to the single value SELECT, we can use it for a database table column. Here is an example:

This simple example will retrieve your company name from table OADM.

The formal query should be this:

It is an important step to include Alias (T0) and Database Owner (dbo) for the table in the query. It will ensure the query's consistency and efficiency. This topic will be discussed in the FROM clause in more detail.

Return a group of database table columns

There is no big difference with the previous example. We can use the same principle to select multiple database table columns. For instance:

This example will retrieve not only your company name, but also your company's address, country, and phone number from table OADM.

The formal query should be as follows:

Return complete database table columns

This is the simplest query to return all column values from table. That is:

This example will retrieve every single column from table OADM. There is no need to assign alias to the query because this kind of query is usually a one-time only query. Here, * is a wildcard that represents everything in the table.

Note

Be careful when running SELECT * from a huge table such as JDT1. It may affect your system's performance! If you are not sure about the table size, it is safer for you to always include the WHERE clause with reasonable restrictions. Or you can run SELECT COUNT(*) FROM the table you want to query first. If the number is high, do not run it without a condition clause.

SELECT can be used in a subquery within SELECT column(s). The topic of using SELECT for subqueries will be discussed in the last chapter of the book, since it needs above average experience level to use it sufficiently.

The numbers of columns to be included

How many columns are suitable for a query? I don't think there are any standard answers. In my experience, I can only suggest to you: the shorter, the better.

Some people have the tendency to include all information in one report. This kind of request may even come from certain executives of the company's management.

One simple test would be a fair criterion. Can you fit the query result within the query result window? If you can, great; that would be a proper number of columns. If not, then I would strongly suggest you double check every column to see if you can cut one or more of them out.

If it is a query for alert, it needs even more special care. The column numbers in any alert queries have to be trimmed to the minimum. Otherwise, you may only get part of the result due to the query result size limitation. You will get more explanation for this issue in the chapter for alert queries.

If you are requested to create super long and wide queries, explain the consequences to the person in charge. Sometimes, they can change their mind depending on the way you communicate with them. In my experience, if a print out report cannot be handled within the width of a page, it might make the report difficult to read. Show the result to a non-technical person. It is easily understandable when you can bring the first hand output to the report readers.

Column names usually come directly from column descriptions, if you have not reassigned them in the query. You can, however, change them to make the query result more useful for special cases. Some people use this method to translate the description into their local language. Some people use it to make the column description more clear.

For some of the value-only columns or formula columns it is mandatory to assign descriptions, otherwise the column headings would be empty. This not only looks unprofessional, but you will also have no way to export the query results to Excel for those columns without the description.

You can use single or double quotation marks for the description. If the description has only one word, you can even omit the quotation mark. The syntax is shown next:

You can omit AS, so that you just keep [ColumnName] 'Description Here'. However, whenever possible, you should keep the AS to make the query script more consistent.

Clauses can follow this statement

Not many clauses can directly follow a SELECT statement. The short list we discuss here is this:

These two clauses will be discussed one by one as follows.

DISTINCT—duplicated records can be removed

A DISTINCT clause is used for getting rid of duplicated records to return only distinct (different) values.

The syntax of this clause is:

column_name and table_name are self explanatory. They represent column name and table name respectively. There will be no additional denotation for these two clauses in this book. A DISTINCT clause is always the first one after the SELECT statement. It is optional. When you specify Distinct in the query, it will not allow any identical rows in the query result. All lines are unique from each other.

Some users claim this clause may still allow duplicate rows. This can never be true. The fact is: although most of the values are the same between two lines, the query results always include at least one column, which contains the different values. Those columns have to be taken out in order to benefit from this clause. You cannot get both the DISTINCT working and some columns which have different values within the scope you selected.

Tip

There are criticisms of this clause because it adds burden to the SQL Server. Be careful while using it if the result-set is huge. You can reduce the amount of the data returned by restricting the query scope within a specific date range.

TOP—number of lines returned by ranking

A TOP clause is used to specify the maximum number of records to return in a query result-set. It is usually used together with the Order By clause at the end of the query.

The syntax of the clause is as follows:

The query result can be the top 10 sales orders, for example. In this case, descending order must be used for the document amounts. Or you may get the top 20 percent purchase invoices, if you specify the TOP by percentage. When you use percentage, you need to write

20 percent instead of 20% after SELECT TOP.

The WITH TIES option specifies the additional rows that need to be returned from the base result set with the same value in the ORDER BY columns appearing at the end of the TOP n (PERCENT) rows. TOP...WITH TIES can be specified only if an ORDER BY clause is specified.

Tip

TOP can be very useful on large tables with thousands of records. Returning a large number of records may have an impact on database performance. If you just need part of the result, give the top clause a try.

Microsoft suggests SELECT TOP (n) with parentheses. It is better to follow the suggestion to be safe for the query results.

FROM—data resource can be assigned

It is very clear that FROM means where to find the data. A FROM clause is actually not a standalone statement since it must be used with SELECT. Most queries need this clause because to only assign a fixed value or a group of values would not be very useful. However, this is one of the most often misused parts of SQL queries. More discussion is needed on this clause.

A FROM clause can be followed by the data sources mentioned next:

- A single table

- A group of linked tables

- Multiple tables separated by commas

Tip

If you have read through Chapter 1, SAP Business One Query Users and Query Basic, you should understand the concept of Table and Table Relationships. If you directly jumped here bypassing that previous chapter, you may need to go back to check.

This is the simplest query including a FROM statement. A simple example:

This will only touch one table—OUDP. This table is for a department. You can get the Department Code, Department Name, and the Description from the query result.

The better format would be:

Now, it is time to explain why those additional T0 and dbo are necessary here.

Actually, it may not make any difference if we only deal with this particular query and this query is only run by one user. However, that is not generally true. In most cases, we often have more than one table and more than one user to run the same query.

T0 here stands for an Alias of OUDP table. It is the standard convention and most frequently used alias. T means table. 0 is a sequence number. You can have T0, T1, T2, …until Tn. If you have 10 tables in the query, n would be equal to 9 for alias. This naming convention is convenient to use. You just need to name them in sequential numbers.

The syntax for table alias looks like this:

An alias table name can be anything, but usually it is the shortest possible one.

If a query is not created by query tools, it is not mandatory for alias to take the Tn sequence. You may just use A, B, C, …… to have one letter shorter than the standard way, or make them easier to remember. However, it is advisable that you follow the norm. It can save you time for maintaining your query in the long run.

Tip

When you have more than 10 tables in the query, an A, B, C, …… sequence would be better than the normal T0, T1, T2, …… convention because T10 and above need more spaces.

The function for alias is mainly for saving resources. If no alias is defined, you have to enter the full table names for every single column in the query. Be careful when you are using alias; you should use alias exclusively throughout your query. You are not allowed to mix them with the actual table name. In other words, you may only use alias or the actual table name, but you are not allowed to use them both in the same query.

The other added word dbo means Database Owner. This is a special database user. This user has implied permissions to perform all activities in the database. All tables of SAP Business One have the owner of dbo. It is useful to add dbo in front of a table name when you have more than one user running the query, but this is beyond the scope of the book. I will try to use the simplest method to give you a rough idea.

Query running needs an execution plan. A query execution plan (or query plan) outlines how the SQL Server query optimizer (query optimizer is too complicated to explain here, you just need to know it is a tool built into SQL server) actually ran (or will run) a specific query. There are typically a large number of alternate ways to execute a given query, with widely varying performance. When a query is submitted to the database, the query optimizer evaluates some of the different, correct possible plans for executing the query and returns what it considers the best alternative. This information is very valuable when it comes to finding out why a specific query is running slowly.

The hard fact is: no one can control this plan manually at runtime. Once a plan is created, it is reusable for the same user to run the query. If you are not entering dbo in front of the table name, the query will check every user who runs the query. A new plan may be added for every new user because the owner is not included in the query body. That might cause too much unnecessary burden to the database.

Tip

To save time and increase your system performance, dbo is highly recommended in front of table names for every query unless they are only for temporary use. These three letters mean database performance gain. Do not ignore, but add them to your query!

This is the category that most queries will be included in. One example may not be enough to show this clearly. You have two query examples to show. The first one is as follows:

This query links ADOC (Document History) and ORIN (Credit Memo Headers) tables to show the credit memo document number, document type, user information, and the change log user code for the credit memo. A detailed explanation can be found in the next chapter.

The second query example is as follows:

This query links five tables OCRD (Business Partners), ORCT (Incoming Payment Headers), RCT2 (Incoming Payments—Invoices), OSLP (Sales Employees), and OINV (Invoice Headers) together. It shows customers' payment with invoice details. Again, the business case explanation is available in the next chapter.

Among the five links in the query, there are two different kinds of links. One is INNER JOIN. The other is LEFT JOIN; more explanation of these joins can be found later in the chapter.

Tip

Again, one special case needs to be pointed out here. If your table is a User Defined Table (UDT), do not forget that @ is the first letter of your table name.

Multiple tables separated by commas

When you link tables together, SQL Server just treats them as a view, or it acts as one big table. However, there is another way to add your tables into the query without linking them first. The syntax is similar to comma delimited columns. You simply need to enter a comma in between tables. In this case, table linking has to be done under the WHERE conditions.

Technically, the way of linking tables without joining is the most ideal method because you can get the minimum records out with the least database operations, if you are very good at database structure. However, like the difference between manual and automatic cameras, most people prefer automatic cameras because it is very convenient, especially if you do not have extensive training or extraordinary experience, and the ideal manual control may not help you get a better picture!

I always refuse to create queries without joining the tables first. Comma-separated table query is too dangerous. If you have the wrong conditions defined in the WHERE clause, you may end up with countless loops. In the worst case scenario, it may lock your system up. On the contrary, if you link all tables together, the worst case scenario would be no results because of a bad link or bad conditions.

In other words, if you want to add all tables' linking conditions under the WHERE clause, you are giving yourself an unnecessary burden in making sure they are correct. Those verifications have to be done manually.

Whenever possible, you are better to avoid using comma separated table queries. In most cases, it may use more resources and put you at a higher risk of system instability.

JOIN—addition table or tables can be linked

You have learned the FROM statement. With this statement, you know that more than one table can be put into one query.

In most cases, those additional tables should be linked together. The reason we need to link tables before the WHERE clause has been discussed in the previous paragraph. To link those extra tables, JOIN is used to combine rows from multiple tables.

A join is performed whenever two or more tables are listed in the FROM clause of a SQL statement without using a comma to separate them. Joined tables must include at least one common column in both tables that contain comparable data. Column names across tables don't have to be the same. But if we have the same name columns to join with correct relation, use them first.

There are different types of JOIN statements to be discussed, listed as follows:

- Inner join

- Outer joins

- Self-join

One of the special join types is omitted from the list. This is called the Cross Join. This type of join can list all possible combinations of your linked tables. You may end up with 90,000 lines of huge output even if you have only 300 records in each table. I have no idea who can benefit from this Cross Join. They must be very special.

First, let's look at the most commonly used one.

An INNER JOIN is also called a Simple Join. It is the simplest table join. INNER JOIN is the default link type to join tables. You may even omit INNER to leave only JOIN. When you see JOIN without any words in front, it means INNER JOIN. In order to distinguish other types of JOIN, omission is not encouraged unless your query length is an issue that requires you to reduce your query to the minimum size.

An INNER JOIN syntax looks like the following:

In an INNER JOIN statement, the link is defined by the keyword ON with common columns from each table to retrieve the matching records from those tables. To link two or more tables correctly, the linking columns are very important. INNER JOIN will select all rows from linked tables as long as there is a match between the columns you are matching on. If you forget the keyword ON in the joined table list, you will get an error message right away when you try to run the query.

The best way to link tables is by using the Key Columns such as the primary key or the foreign key. That is because Key Columns are usually indexed. That makes links easier and faster. In case there is no such columns' pair to link, care must be taken to select the best efficient common columns between tables. When you have more than one way to link, you can consider the shorter columns first.

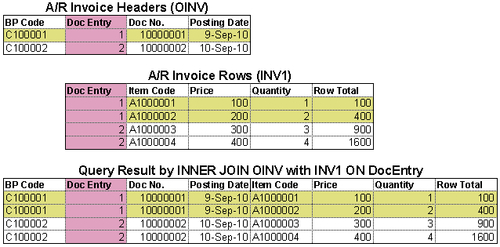

The previous example shows a real query about how an inner join works.

The query script is:

Two tables, OINV (A/R invoice headers) and INV1 (A/R invoice rows), are joined by DocEntry columns. This DocEntry column is actually not included in the query result. It is only for illustration purposes for easier understanding. From the previous example, you can see how INNER JOIN works. For DocEntry 1 and 2, two rows each are formed by the query. The query result shows four lines in total.

You should avoid linking by lengthy text only columns. To match those columns, not only system performance becomes an issue, but also no ideal query results might be shown. In general, if the column length is over 30 characters, the link efficiency will be reduced dramatically.

Keep in mind, an inner join will effectively filter your query result by linking columns. If there are no common values between linked columns, those records are going to be dropped out. If you find that the query result does not meet your requirements, some other types of joins can be used instead.

Some may call OUTER JOIN a complex join. Actually, it may not be that complicated at all and is only a little bit more complicated than INNER JOIN. You do not need to worry about the complexity. When you find the true meaning of OUTER JOIN, it is similar and comparable with INNER JOIN.

There are three types of Outer Joins:

- Left Outer Join

- Right Outer Join

- Full Outer Join

We will examine each type as follows.

A LEFT OUTER JOIN is one of the most used outer joins in queries. Outer here is optional. It can be omitted so that you just need LEFT JOIN. There is no added benefit to using the full name of LEFT OUTER JOIN. Unless a query is automatically created, you should keep using only LEFT JOIN.

A LEFT JOIN clause syntax looks like the following:

In the previous syntax, the first table table_name0 T0 is the LEFT table, while table_name1 T1 is the right table. LEFT JOIN means all records in the left table will be returned, regardless of the right table linking condition. If the match cannot be found in T1 table, it simply returns Null value for any columns coming from T1 table.

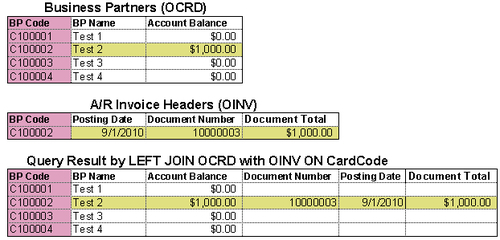

A LEFT JOIN is very useful when you need to display all data records from one table but also want to know some secondary table data without restricting the query results. You will find more examples in the next chapter. If you are still not very clear about this LEFT JOIN clause, I hope the following example can help you:

The previous example shows a real query about how LEFT JOIN works.

The query script is as follows:

From the example, you can get a clear view. If you can only find one BP Code C100002 in the right table (OINV), you will get only one line with full information. All other lines will still show left table columns though.

One thing is important for a LEFT JOIN: do not use secondary Left Join if possible. Suppose you put more than one level of LEFT JOIN; the query result may become less clear.

A Right Outer Join is not used as often as a LEFT JOIN in a query. OUTER here is also optional. It can be omitted so that you just need RIGHT JOIN.

A RIGHT JOIN clause syntax looks like the following:

In the previous syntax, the second table table_name1 T1 is the right table while table_name0 T0 is the left table. A RIGHT JOIN means all records in the right table will be returned, regardless of the left table linking condition. If the match cannot be found in T0 table, it simply returns Null value for any columns coming from the T0 table.

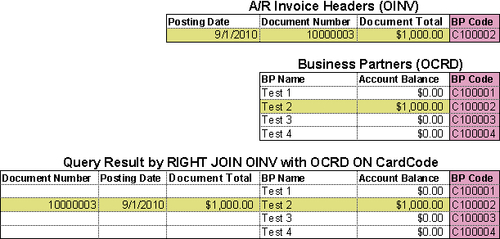

Most people would be more interested in the first table than the second table. That is why not so many people use this RIGHT JOIN. Here is an example for you:

The query script is as follows:

Unless you are used to reading from right to left, I bet no user prefers this result instead of the LEFT JOIN.

A Full Outer Join syntax looks like the following:

A Full Outer Join will return all rows from both tables, regardless of matching conditions. It is one of the most dangerous clauses for SELECT queries too. Try to avoid this kind of join wherever you have other options.

There is no example query for this kind of join because it may only be useful in very special cases.

For people who like to use a Full Outer Join, you should always check what alternatives you have. If only Full Outer Join can solve your issue, some big problems might be hidden. Check them out!

A Self-Join is a special join in which a table is joined to itself. Self-Joins are used to compare values in a column with other values in the same column in the same table. It can be used for certain special needs such as obtaining running counts or running totals in a SQL query. It is often used in subqueries.

To write a query that includes a Self-Join, select from the same table listed twice with different aliases, set up the comparison, or eliminate cases where a particular value would be equal to itself.

A Self-Join is mostly an INNER JOIN. However, it can also be an OUTER JOIN. It is all dependent on your needs.

To my knowledge, this join is only a particular type of INNER JOIN or OUTER JOIN. The classification makes it outstanding only because it is too special.

You will get some example queries of Self-Join in later chapters.

WHERE—query conditions to be defined

It is very clear that the WHERE clause is to define query conditions. By using the WHERE clause, you may extract only those records that fulfill a specified criterion.

The WHERE clause is optional. However, it is a good idea to make it mandatory for your own sake to keep your query results safer. When you create your query without a WHERE clause, all records will be retrieved no matter how big the table is. It is highly recommended that you put the WHERE clause for all of your query scripts before you test to run them. This can save you much more time if you just enter these few letters.

If the WHERE clause exists in a query, it always follows the FROM clause. Its syntax is as follows:

In the previous syntax, expression stands for a column name, a constant, a function, a variable, or a subquery. An operator can be set from the following list:

If a column used in the WHERE clause is one of the character data types, the value must be enclosed in single quotes. In contrast, if the column used in the WHERE clause is of a numeric data type, the value should not be enclosed. The numeric values enclosed in quotes will always return 0.

To make the WHERE clause more efficient, it is better to avoid using Not Equal (<> /!=) wherever possible. Some of the other conditions with NOT also need to be used with care.

Five operators include >, <, =, >=, and <= symbols are very common for comparisons. They are not needed for the purpose of this book. Therefore they are omitted from the examples. Only three special comparisons will be discussed next.

BETWEEN—ranges to be defined from lower to higher end

A BETWEEN operator is to specify a range to test.

The syntax for a BETWEEN operator is:

All arguments are discussed as follows:

- Value1 is the value to be tested in the range defined by Value2 and Value3.

- NOT specifies that the result of the predicate be negated. It is optional.

- Value1 is any valid value with the same data type as Values.

- Value3 is any valid value that is greater than Value2 with the same data type.

- AND is mandatory and acts as a placeholder that indicates Value1 should be within the range indicated by Value2 and Value3.

- This clause is equivalent to Value1 >= Value2 and Value1 <= Value3.

- When you use BETWEEN, it means that the start value and end value are included. If you need to specify an exclusive range, you have to use the greater than (>) and less than (<) operators instead.

There is a condition in the first query example in this chapter before discussing the statement:

Actually, it is equivalent to the following:

The query result is exactly the same. I have chosen to use the longer expression only because the system prompt for the first one is better and clear.

Tip

Be careful; if any input to the BETWEEN or NOT BETWEEN predicate is null, the result is UNKNOWN. When you do not get the desired result, check if there is Null involved. If you are not sure about the data having NULL or not, you better not use BETWEEN at all.

IN/EXISTS—the value list that may satisfy the condition

IN or NOT IN is an operator to compare a value with an existing value list that has more than one value. You are allowed to have only one value in the list. However, that should be by equal operator. It is not logical to define only one value in the list. An IN operator can be used to determine whether a specified value matches or does not match any values in a list. The list can be a result of a subquery. This subquery must have only one column to return. In order for two sides to be comparable, both sides must have matched data types.

This operator is similar to the OR condition but is much shorter. With the OR condition, you not only have to repeat the similar conditions one by one, but you also need parentheses if there are other co-existing conditions.

In the list to be compared, duplicate values are allowed. You do not need to specify the DISTINCT keyword if the same values are the same. After all, you are comparing the left side value to the right side value list. The result will be the same no matter how many times the same values present in the list are compared with.

Any null values returned by a subquery or a list that are to be compared using IN or NOT IN will return UNKNOWN. It can produce unexpected results. Get rid of the Null value for the list wherever possible.

EXISTS or NOT EXISTS is also an operator to compare a value with a list. The list is only a result of a subquery. This subquery can have more than one column to return. In order for two sides to be comparable, both sides must have matched data types.

IN and EXISTS are almost the same, only that IN allows both fixed list and subquery. The only other exception is the way they treat Null values. If the subquery contains Null value, EXISTS will perform better than IN. This is because EXISTS only cares if the value exists in the query result. It doesn't care if there is Null value or not.

The bottom line is: whenever using these operators, predict if you may get Null values. Choose a proper one based on the prediction.

LIKE—similar records can be found

A LIKE operator allows you to do a search based on a pattern rather than specifying exactly what is desired (as in IN) or spell out a range (as in BETWEEN). LIKE determines whether a value to be tested matches a specified pattern. A pattern can include wildcard characters. During this matching, wildcard characters play flexible roles to allow partly unmatched values to go through.

Using wildcard characters makes the LIKE operator more flexible than using the = or != string comparison operators. In case any one of the values is not of the character string data type, the SQL Server Database Engine converts them to character string data type if possible.

A LIKE operator syntax is as follows:

Two arguments are as follows:

- Value is any valid value of character string data type.

- Pattern is the specific string of characters to search for in the Value, and can include the following valid wildcard characters. Pattern can be a maximum of 8,000 bytes.

Most of the LIKE operators include % and/or _ wildcard characters. % can be put in the front, in the middle, or at the end. If you can find a certain condition such as A LIKE 'xy%' instead of A LIKE '%xy', the query result would be faster.

Although NOT is an optional keyword for LIKE, you should try to avoid it in any way possible. It is not an effective way to compare a value with any patterns.

GROUP BY—summarizing the data according to the list

A GROUP BY clause is very useful if you need to aggregate your data based on certain columns. It is optional and must follow the FROM and WHERE clauses.

If you remember the first query before discussing statements, you have:

GROUP BY specifies T0.ShortName i.e. Business Partner column would be the base for summarizing debit and credit amounts for each Business Partner.

Whenever you use the GROUP BY clause, it is mandatory to include all your columns under this clause unless they are aggregated columns.

The following example shows a simple query:

The query script is simple:

In the previous example, neither the DocNum nor the DocTotal columns can be included in the query. Otherwise, the group will not work for each customer.

HAVING—conditions to be defined in summary report

A HAVING clause is normally used with a GROUP BY clause. This clause is optional. It is equivalent to a WHERE clause under the main query body. It specifies that a SELECT statement should only return rows where aggregate values meet the specified conditions. This clause was added to the SQL language after the main clause had already been defined because the WHERE keyword could not be used with aggregate functions.

If you remember the first query before discussing, you have:

It can be found under the GROUP BY clause in the query. This means the query result will only include those records if the aggregate summary function's result of T0.Debit minus T0.Credit is greater than zero. In case there are Null values, they will be replaced with zero from all occurrences before summary operation.

ORDER BY—report result can be by your preferred order

An ORDER BY clause is very simple when you need to sort your query result based on certain columns. This clause is always the last clause to be used in the query. If you have UNION or UNION ALL to combine more than one query, this clause may only be added to the end of the entire query.

There are two types of orders: One is ascending and the other is descending. Descending can be abbreviated to DESC in the end. Ascending can be abbreviated to ASC. If DESC is not included, the default ORDER BY will be ascending. Since ascending is the default order, it is usually omitted from the query.

An ORDER BY clause can have more than one column. The rule for query result is: the order first applies to the first column in the left. Then will be the second column, the third column, and so on.

Remember, not all types of columns are orderable. Some image columns, memo columns, etc. cannot be ordered.

If you remember the first query before the discussion statement, the last statement is as follows:

It means the query result will be ordered by descending order according to the summary of T0.Debit minus T0.Credit. If there are Null values, they will be replaced with zero for all occurrences.

UNION/UNION ALL—to put two or more queries together

The UNION clause combines the results of two or more SQL queries into one query result set. To use this clause, the number and order of columns from those queries must be the same with compatible data types. Any duplicate records are automatically removed by the UNION clause. It works like DISTINCT.

One thing you need to be aware of: UNION results do not care about the order of the rows. Rows from the first query may appear before, after, or mixed with rows from the following one. If you need a specific order, the ORDER BY clause must be used.

The UNION ALL clause is almost the same as the UNION clause, except it allows duplicated records.

UNION ALL may be much faster than plain UNION due to fewer checks in the query process. Whenever duplication is not a concern, or duplication is needed, UNION ALL should be used first.

A UNION or UNION ALL query is usually longer than a normal query because it is at least double the lines of query scripts. The example query that includes this clause will be shown in later chapters.

SELECT—first statement to retrieve data

It is quite obvious from the meaning of the word that SELECT is used to display or retrieve data from certain data sources.

The SELECT statement is used to return data from a set of values or database tables.

The result is stored in a result table, called the result-set.

SELECT is one of the most commonly used Data Manipulation Language (DML) commands. It seems very simple. However, something important needs to be explained for this statement:

- The scope of the value that can be retrieved

- The numbers of columns to be included

- Column name descriptions

- Keywords followed to this statement

The scope of the value that can be retrieved

Here is a return value list that SELECT can be used for:

- A single value

- A group of values

- Return a single database table column

- Return a group of database table columns

- Return complete database table columns

- Used in a subquery

The simplest SELECT query would be just to get a constant or text without any additional statements. An example would be:

These queries will display Yes or 10 in one column when executed.

You may also use this statement to get a group of values. For example:

This query will display Yes, 10, This is an example in three columns named Yes/No, No., and Content when you execute it.

Some special uses of this statement to display a single value or group of values will be discussed in other chapters when we introduce more specific topics.

Please note the comma used above. Following the SELECT statement, each comma will define a new column to be displayed.

Tip

Do not forget to delete the last comma in a SELECT statement. This simple mistake is one of the most frequent problems for a query. It is mainly due to the fact that we are often used to copying columns in our queries, which include the comma, and forget to remove the last one before testing the query.

Return a single database table column

Similar to the single value SELECT, we can use it for a database table column. Here is an example:

This simple example will retrieve your company name from table OADM.

The formal query should be this:

It is an important step to include Alias (T0) and Database Owner (dbo) for the table in the query. It will ensure the query's consistency and efficiency. This topic will be discussed in the FROM clause in more detail.

Return a group of database table columns

There is no big difference with the previous example. We can use the same principle to select multiple database table columns. For instance:

This example will retrieve not only your company name, but also your company's address, country, and phone number from table OADM.

The formal query should be as follows:

Return complete database table columns

This is the simplest query to return all column values from table. That is:

This example will retrieve every single column from table OADM. There is no need to assign alias to the query because this kind of query is usually a one-time only query. Here, * is a wildcard that represents everything in the table.

Note

Be careful when running SELECT * from a huge table such as JDT1. It may affect your system's performance! If you are not sure about the table size, it is safer for you to always include the WHERE clause with reasonable restrictions. Or you can run SELECT COUNT(*) FROM the table you want to query first. If the number is high, do not run it without a condition clause.

SELECT can be used in a subquery within SELECT column(s). The topic of using SELECT for subqueries will be discussed in the last chapter of the book, since it needs above average experience level to use it sufficiently.

The numbers of columns to be included

How many columns are suitable for a query? I don't think there are any standard answers. In my experience, I can only suggest to you: the shorter, the better.

Some people have the tendency to include all information in one report. This kind of request may even come from certain executives of the company's management.

One simple test would be a fair criterion. Can you fit the query result within the query result window? If you can, great; that would be a proper number of columns. If not, then I would strongly suggest you double check every column to see if you can cut one or more of them out.

If it is a query for alert, it needs even more special care. The column numbers in any alert queries have to be trimmed to the minimum. Otherwise, you may only get part of the result due to the query result size limitation. You will get more explanation for this issue in the chapter for alert queries.

If you are requested to create super long and wide queries, explain the consequences to the person in charge. Sometimes, they can change their mind depending on the way you communicate with them. In my experience, if a print out report cannot be handled within the width of a page, it might make the report difficult to read. Show the result to a non-technical person. It is easily understandable when you can bring the first hand output to the report readers.

Column names usually come directly from column descriptions, if you have not reassigned them in the query. You can, however, change them to make the query result more useful for special cases. Some people use this method to translate the description into their local language. Some people use it to make the column description more clear.

For some of the value-only columns or formula columns it is mandatory to assign descriptions, otherwise the column headings would be empty. This not only looks unprofessional, but you will also have no way to export the query results to Excel for those columns without the description.

You can use single or double quotation marks for the description. If the description has only one word, you can even omit the quotation mark. The syntax is shown next:

You can omit AS, so that you just keep [ColumnName] 'Description Here'. However, whenever possible, you should keep the AS to make the query script more consistent.

Clauses can follow this statement

Not many clauses can directly follow a SELECT statement. The short list we discuss here is this:

These two clauses will be discussed one by one as follows.

DISTINCT—duplicated records can be removed

A DISTINCT clause is used for getting rid of duplicated records to return only distinct (different) values.

The syntax of this clause is:

column_name and table_name are self explanatory. They represent column name and table name respectively. There will be no additional denotation for these two clauses in this book. A DISTINCT clause is always the first one after the SELECT statement. It is optional. When you specify Distinct in the query, it will not allow any identical rows in the query result. All lines are unique from each other.

Some users claim this clause may still allow duplicate rows. This can never be true. The fact is: although most of the values are the same between two lines, the query results always include at least one column, which contains the different values. Those columns have to be taken out in order to benefit from this clause. You cannot get both the DISTINCT working and some columns which have different values within the scope you selected.

Tip

There are criticisms of this clause because it adds burden to the SQL Server. Be careful while using it if the result-set is huge. You can reduce the amount of the data returned by restricting the query scope within a specific date range.

TOP—number of lines returned by ranking

A TOP clause is used to specify the maximum number of records to return in a query result-set. It is usually used together with the Order By clause at the end of the query.

The syntax of the clause is as follows:

The query result can be the top 10 sales orders, for example. In this case, descending order must be used for the document amounts. Or you may get the top 20 percent purchase invoices, if you specify the TOP by percentage. When you use percentage, you need to write

20 percent instead of 20% after SELECT TOP.

The WITH TIES option specifies the additional rows that need to be returned from the base result set with the same value in the ORDER BY columns appearing at the end of the TOP n (PERCENT) rows. TOP...WITH TIES can be specified only if an ORDER BY clause is specified.

Tip

TOP can be very useful on large tables with thousands of records. Returning a large number of records may have an impact on database performance. If you just need part of the result, give the top clause a try.

Microsoft suggests SELECT TOP (n) with parentheses. It is better to follow the suggestion to be safe for the query results.

FROM—data resource can be assigned

It is very clear that FROM means where to find the data. A FROM clause is actually not a standalone statement since it must be used with SELECT. Most queries need this clause because to only assign a fixed value or a group of values would not be very useful. However, this is one of the most often misused parts of SQL queries. More discussion is needed on this clause.

A FROM clause can be followed by the data sources mentioned next:

- A single table

- A group of linked tables

- Multiple tables separated by commas

Tip

If you have read through Chapter 1, SAP Business One Query Users and Query Basic, you should understand the concept of Table and Table Relationships. If you directly jumped here bypassing that previous chapter, you may need to go back to check.

This is the simplest query including a FROM statement. A simple example:

This will only touch one table—OUDP. This table is for a department. You can get the Department Code, Department Name, and the Description from the query result.

The better format would be:

Now, it is time to explain why those additional T0 and dbo are necessary here.

Actually, it may not make any difference if we only deal with this particular query and this query is only run by one user. However, that is not generally true. In most cases, we often have more than one table and more than one user to run the same query.

T0 here stands for an Alias of OUDP table. It is the standard convention and most frequently used alias. T means table. 0 is a sequence number. You can have T0, T1, T2, …until Tn. If you have 10 tables in the query, n would be equal to 9 for alias. This naming convention is convenient to use. You just need to name them in sequential numbers.

The syntax for table alias looks like this:

An alias table name can be anything, but usually it is the shortest possible one.

If a query is not created by query tools, it is not mandatory for alias to take the Tn sequence. You may just use A, B, C, …… to have one letter shorter than the standard way, or make them easier to remember. However, it is advisable that you follow the norm. It can save you time for maintaining your query in the long run.

Tip

When you have more than 10 tables in the query, an A, B, C, …… sequence would be better than the normal T0, T1, T2, …… convention because T10 and above need more spaces.

The function for alias is mainly for saving resources. If no alias is defined, you have to enter the full table names for every single column in the query. Be careful when you are using alias; you should use alias exclusively throughout your query. You are not allowed to mix them with the actual table name. In other words, you may only use alias or the actual table name, but you are not allowed to use them both in the same query.

The other added word dbo means Database Owner. This is a special database user. This user has implied permissions to perform all activities in the database. All tables of SAP Business One have the owner of dbo. It is useful to add dbo in front of a table name when you have more than one user running the query, but this is beyond the scope of the book. I will try to use the simplest method to give you a rough idea.

Query running needs an execution plan. A query execution plan (or query plan) outlines how the SQL Server query optimizer (query optimizer is too complicated to explain here, you just need to know it is a tool built into SQL server) actually ran (or will run) a specific query. There are typically a large number of alternate ways to execute a given query, with widely varying performance. When a query is submitted to the database, the query optimizer evaluates some of the different, correct possible plans for executing the query and returns what it considers the best alternative. This information is very valuable when it comes to finding out why a specific query is running slowly.

The hard fact is: no one can control this plan manually at runtime. Once a plan is created, it is reusable for the same user to run the query. If you are not entering dbo in front of the table name, the query will check every user who runs the query. A new plan may be added for every new user because the owner is not included in the query body. That might cause too much unnecessary burden to the database.

Tip

To save time and increase your system performance, dbo is highly recommended in front of table names for every query unless they are only for temporary use. These three letters mean database performance gain. Do not ignore, but add them to your query!

This is the category that most queries will be included in. One example may not be enough to show this clearly. You have two query examples to show. The first one is as follows:

This query links ADOC (Document History) and ORIN (Credit Memo Headers) tables to show the credit memo document number, document type, user information, and the change log user code for the credit memo. A detailed explanation can be found in the next chapter.

The second query example is as follows:

This query links five tables OCRD (Business Partners), ORCT (Incoming Payment Headers), RCT2 (Incoming Payments—Invoices), OSLP (Sales Employees), and OINV (Invoice Headers) together. It shows customers' payment with invoice details. Again, the business case explanation is available in the next chapter.

Among the five links in the query, there are two different kinds of links. One is INNER JOIN. The other is LEFT JOIN; more explanation of these joins can be found later in the chapter.

Tip

Again, one special case needs to be pointed out here. If your table is a User Defined Table (UDT), do not forget that @ is the first letter of your table name.

Multiple tables separated by commas

When you link tables together, SQL Server just treats them as a view, or it acts as one big table. However, there is another way to add your tables into the query without linking them first. The syntax is similar to comma delimited columns. You simply need to enter a comma in between tables. In this case, table linking has to be done under the WHERE conditions.

Technically, the way of linking tables without joining is the most ideal method because you can get the minimum records out with the least database operations, if you are very good at database structure. However, like the difference between manual and automatic cameras, most people prefer automatic cameras because it is very convenient, especially if you do not have extensive training or extraordinary experience, and the ideal manual control may not help you get a better picture!

I always refuse to create queries without joining the tables first. Comma-separated table query is too dangerous. If you have the wrong conditions defined in the WHERE clause, you may end up with countless loops. In the worst case scenario, it may lock your system up. On the contrary, if you link all tables together, the worst case scenario would be no results because of a bad link or bad conditions.

In other words, if you want to add all tables' linking conditions under the WHERE clause, you are giving yourself an unnecessary burden in making sure they are correct. Those verifications have to be done manually.

Whenever possible, you are better to avoid using comma separated table queries. In most cases, it may use more resources and put you at a higher risk of system instability.

JOIN—addition table or tables can be linked

You have learned the FROM statement. With this statement, you know that more than one table can be put into one query.

In most cases, those additional tables should be linked together. The reason we need to link tables before the WHERE clause has been discussed in the previous paragraph. To link those extra tables, JOIN is used to combine rows from multiple tables.

A join is performed whenever two or more tables are listed in the FROM clause of a SQL statement without using a comma to separate them. Joined tables must include at least one common column in both tables that contain comparable data. Column names across tables don't have to be the same. But if we have the same name columns to join with correct relation, use them first.

There are different types of JOIN statements to be discussed, listed as follows:

- Inner join

- Outer joins

- Self-join

One of the special join types is omitted from the list. This is called the Cross Join. This type of join can list all possible combinations of your linked tables. You may end up with 90,000 lines of huge output even if you have only 300 records in each table. I have no idea who can benefit from this Cross Join. They must be very special.

First, let's look at the most commonly used one.

An INNER JOIN is also called a Simple Join. It is the simplest table join. INNER JOIN is the default link type to join tables. You may even omit INNER to leave only JOIN. When you see JOIN without any words in front, it means INNER JOIN. In order to distinguish other types of JOIN, omission is not encouraged unless your query length is an issue that requires you to reduce your query to the minimum size.

An INNER JOIN syntax looks like the following:

In an INNER JOIN statement, the link is defined by the keyword ON with common columns from each table to retrieve the matching records from those tables. To link two or more tables correctly, the linking columns are very important. INNER JOIN will select all rows from linked tables as long as there is a match between the columns you are matching on. If you forget the keyword ON in the joined table list, you will get an error message right away when you try to run the query.

The best way to link tables is by using the Key Columns such as the primary key or the foreign key. That is because Key Columns are usually indexed. That makes links easier and faster. In case there is no such columns' pair to link, care must be taken to select the best efficient common columns between tables. When you have more than one way to link, you can consider the shorter columns first.

The previous example shows a real query about how an inner join works.

The query script is:

Two tables, OINV (A/R invoice headers) and INV1 (A/R invoice rows), are joined by DocEntry columns. This DocEntry column is actually not included in the query result. It is only for illustration purposes for easier understanding. From the previous example, you can see how INNER JOIN works. For DocEntry 1 and 2, two rows each are formed by the query. The query result shows four lines in total.

You should avoid linking by lengthy text only columns. To match those columns, not only system performance becomes an issue, but also no ideal query results might be shown. In general, if the column length is over 30 characters, the link efficiency will be reduced dramatically.

Keep in mind, an inner join will effectively filter your query result by linking columns. If there are no common values between linked columns, those records are going to be dropped out. If you find that the query result does not meet your requirements, some other types of joins can be used instead.

Some may call OUTER JOIN a complex join. Actually, it may not be that complicated at all and is only a little bit more complicated than INNER JOIN. You do not need to worry about the complexity. When you find the true meaning of OUTER JOIN, it is similar and comparable with INNER JOIN.

There are three types of Outer Joins:

- Left Outer Join

- Right Outer Join

- Full Outer Join

We will examine each type as follows.

A LEFT OUTER JOIN is one of the most used outer joins in queries. Outer here is optional. It can be omitted so that you just need LEFT JOIN. There is no added benefit to using the full name of LEFT OUTER JOIN. Unless a query is automatically created, you should keep using only LEFT JOIN.

A LEFT JOIN clause syntax looks like the following:

In the previous syntax, the first table table_name0 T0 is the LEFT table, while table_name1 T1 is the right table. LEFT JOIN means all records in the left table will be returned, regardless of the right table linking condition. If the match cannot be found in T1 table, it simply returns Null value for any columns coming from T1 table.

A LEFT JOIN is very useful when you need to display all data records from one table but also want to know some secondary table data without restricting the query results. You will find more examples in the next chapter. If you are still not very clear about this LEFT JOIN clause, I hope the following example can help you:

The previous example shows a real query about how LEFT JOIN works.

The query script is as follows:

From the example, you can get a clear view. If you can only find one BP Code C100002 in the right table (OINV), you will get only one line with full information. All other lines will still show left table columns though.

One thing is important for a LEFT JOIN: do not use secondary Left Join if possible. Suppose you put more than one level of LEFT JOIN; the query result may become less clear.

A Right Outer Join is not used as often as a LEFT JOIN in a query. OUTER here is also optional. It can be omitted so that you just need RIGHT JOIN.

A RIGHT JOIN clause syntax looks like the following:

In the previous syntax, the second table table_name1 T1 is the right table while table_name0 T0 is the left table. A RIGHT JOIN means all records in the right table will be returned, regardless of the left table linking condition. If the match cannot be found in T0 table, it simply returns Null value for any columns coming from the T0 table.

Most people would be more interested in the first table than the second table. That is why not so many people use this RIGHT JOIN. Here is an example for you:

The query script is as follows:

Unless you are used to reading from right to left, I bet no user prefers this result instead of the LEFT JOIN.

A Full Outer Join syntax looks like the following:

A Full Outer Join will return all rows from both tables, regardless of matching conditions. It is one of the most dangerous clauses for SELECT queries too. Try to avoid this kind of join wherever you have other options.

There is no example query for this kind of join because it may only be useful in very special cases.

For people who like to use a Full Outer Join, you should always check what alternatives you have. If only Full Outer Join can solve your issue, some big problems might be hidden. Check them out!

A Self-Join is a special join in which a table is joined to itself. Self-Joins are used to compare values in a column with other values in the same column in the same table. It can be used for certain special needs such as obtaining running counts or running totals in a SQL query. It is often used in subqueries.

To write a query that includes a Self-Join, select from the same table listed twice with different aliases, set up the comparison, or eliminate cases where a particular value would be equal to itself.

A Self-Join is mostly an INNER JOIN. However, it can also be an OUTER JOIN. It is all dependent on your needs.

To my knowledge, this join is only a particular type of INNER JOIN or OUTER JOIN. The classification makes it outstanding only because it is too special.

You will get some example queries of Self-Join in later chapters.

WHERE—query conditions to be defined

It is very clear that the WHERE clause is to define query conditions. By using the WHERE clause, you may extract only those records that fulfill a specified criterion.

The WHERE clause is optional. However, it is a good idea to make it mandatory for your own sake to keep your query results safer. When you create your query without a WHERE clause, all records will be retrieved no matter how big the table is. It is highly recommended that you put the WHERE clause for all of your query scripts before you test to run them. This can save you much more time if you just enter these few letters.

If the WHERE clause exists in a query, it always follows the FROM clause. Its syntax is as follows:

In the previous syntax, expression stands for a column name, a constant, a function, a variable, or a subquery. An operator can be set from the following list:

If a column used in the WHERE clause is one of the character data types, the value must be enclosed in single quotes. In contrast, if the column used in the WHERE clause is of a numeric data type, the value should not be enclosed. The numeric values enclosed in quotes will always return 0.

To make the WHERE clause more efficient, it is better to avoid using Not Equal (<> /!=) wherever possible. Some of the other conditions with NOT also need to be used with care.

Five operators include >, <, =, >=, and <= symbols are very common for comparisons. They are not needed for the purpose of this book. Therefore they are omitted from the examples. Only three special comparisons will be discussed next.

BETWEEN—ranges to be defined from lower to higher end

A BETWEEN operator is to specify a range to test.

The syntax for a BETWEEN operator is:

All arguments are discussed as follows:

- Value1 is the value to be tested in the range defined by Value2 and Value3.

- NOT specifies that the result of the predicate be negated. It is optional.

- Value1 is any valid value with the same data type as Values.

- Value3 is any valid value that is greater than Value2 with the same data type.

- AND is mandatory and acts as a placeholder that indicates Value1 should be within the range indicated by Value2 and Value3.

- This clause is equivalent to Value1 >= Value2 and Value1 <= Value3.

- When you use BETWEEN, it means that the start value and end value are included. If you need to specify an exclusive range, you have to use the greater than (>) and less than (<) operators instead.

There is a condition in the first query example in this chapter before discussing the statement:

Actually, it is equivalent to the following:

The query result is exactly the same. I have chosen to use the longer expression only because the system prompt for the first one is better and clear.

Tip

Be careful; if any input to the BETWEEN or NOT BETWEEN predicate is null, the result is UNKNOWN. When you do not get the desired result, check if there is Null involved. If you are not sure about the data having NULL or not, you better not use BETWEEN at all.

IN/EXISTS—the value list that may satisfy the condition

IN or NOT IN is an operator to compare a value with an existing value list that has more than one value. You are allowed to have only one value in the list. However, that should be by equal operator. It is not logical to define only one value in the list. An IN operator can be used to determine whether a specified value matches or does not match any values in a list. The list can be a result of a subquery. This subquery must have only one column to return. In order for two sides to be comparable, both sides must have matched data types.

This operator is similar to the OR condition but is much shorter. With the OR condition, you not only have to repeat the similar conditions one by one, but you also need parentheses if there are other co-existing conditions.

In the list to be compared, duplicate values are allowed. You do not need to specify the DISTINCT keyword if the same values are the same. After all, you are comparing the left side value to the right side value list. The result will be the same no matter how many times the same values present in the list are compared with.

Any null values returned by a subquery or a list that are to be compared using IN or NOT IN will return UNKNOWN. It can produce unexpected results. Get rid of the Null value for the list wherever possible.

EXISTS or NOT EXISTS is also an operator to compare a value with a list. The list is only a result of a subquery. This subquery can have more than one column to return. In order for two sides to be comparable, both sides must have matched data types.

IN and EXISTS are almost the same, only that IN allows both fixed list and subquery. The only other exception is the way they treat Null values. If the subquery contains Null value, EXISTS will perform better than IN. This is because EXISTS only cares if the value exists in the query result. It doesn't care if there is Null value or not.

The bottom line is: whenever using these operators, predict if you may get Null values. Choose a proper one based on the prediction.

LIKE—similar records can be found