-

Book Overview & Buying

-

Table Of Contents

MongoDB Fundamentals

By :

MongoDB Fundamentals

By:

Overview of this book

Free Chapter

Free Chapter

Sign In

Start Free Trial

Sign In

Start Free Trial

You have learned how MongoDB stores JSON-like documents. You have also seen various documents and read the information stored within them and seen how flexible these documents are to store different types of data structures, irrespective of the complexity of your data.

In this section, you will learn about the various data types supported by MongoDB's BSON documents. Using the right data types in your documents is very important as correct data types help you use the database features more effectively, avoid data corruption, and improve data usability. MongoDB supports all the data types from JSON and BSON. Let's look at each in detail, with examples.

A string is a basic data type used to represent text-based fields in a document. It is a plain sequence of characters. In MongoDB, the string fields are UTF-8 encoded, and thus they support most international characters. The MongoDB drivers for various programming languages convert the string fields to UTF-8 while reading or writing data from a collection.

A string with plain-text characters appears as follows:

{

"name" : "Tom Walter"

}

A string with random characters and whitespaces will appear as follows:

{

"random_txt" : "a ! *& ) ( f s f @#$ s"

}

In JSON, a value that is wrapped in double quotes is considered a string. Consider the following example in which a valid number and date are wrapped in double quotes, both forming a string:

{

"number_txt" : "112.1"

}

{

"date_txt" : "1929-12-31"

}

An interesting fact about MongoDB string fields is that they support search capabilities with regular expressions. This means you can search for documents by providing the full value of a text field or by providing only part of the string value using regular expressions.

A number is JSON's basic data type. A JSON document does not specify whether a number is an integer, a float, or long:

{

"number_of_employees": 50342

}

{

"pi": 3.14159265359

}

However, MongoDB supports the following types of numbers:

double: 64-bit floating pointint: 32-bit signed integerlong: 64-bit unsigned integerdecimal: 128-bit floating point – which is IEE 754-compliantWhen you are working with a programming language, you don't have to worry about these data types. You can simply program using the language's native data types. The MongoDB drivers for respective languages take care of encoding the language-specific numbers to one of the previously listed data types.

If you are working on the mongo shell, you get three wrappers to handle: integer, long, and decimal. The Mongo shell is based on JavaScript, and thus all the documents are represented in JSON format. By default, it treats any number as a 64-bit floating point. However, if you want to explicitly use the other types, you can use the following wrappers.

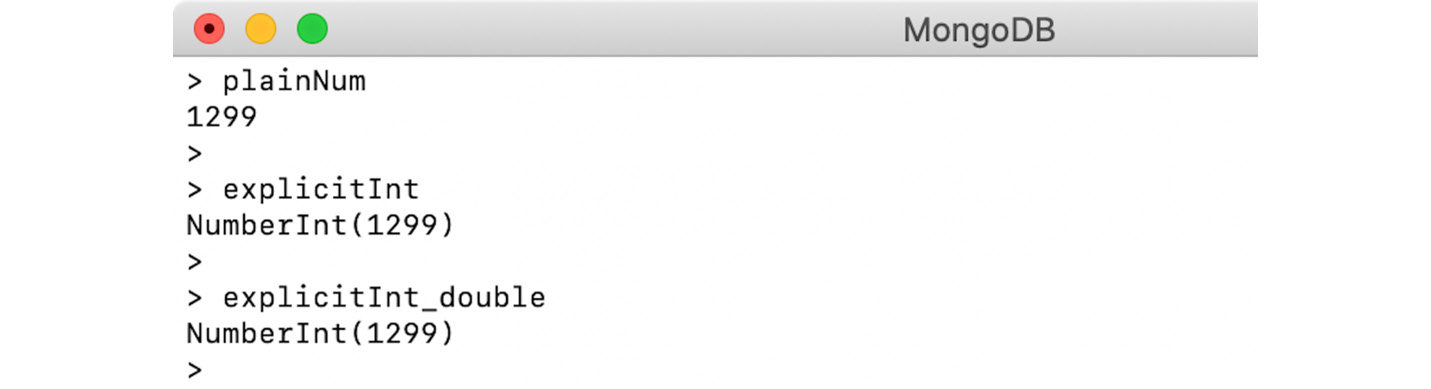

NumberInt: The NumberInt constructor can be used if you want the number to be saved as a 32-bit integer and not as a 64-bit float:

> var plainNum = 1299

> var explicitInt = NumberInt("1299")

> var explicitInt_double = NumberInt(1299)

plainNum, is initialized with a sequence of digits without mentioning any explicit data type. Therefore, by default, it will be treated as a 64-bit floating-point number (also known as a double).explicitInt, however, is initialized with an integer-type constructor and a string representation of a number, and so MongoDB reads the number in an argument as a 32-bit integer.explicitInt_double initialization, the number provided in the constructor argument doesn't have double quotes. Therefore, it will be treated as a 64-bit float—that is, a double—and used to form a 32-bit integer. But as the provided number fits in the integer range, no change is seen.

Figure 2.4: Output for the plainNum, explicitInt, and explicitInt_double

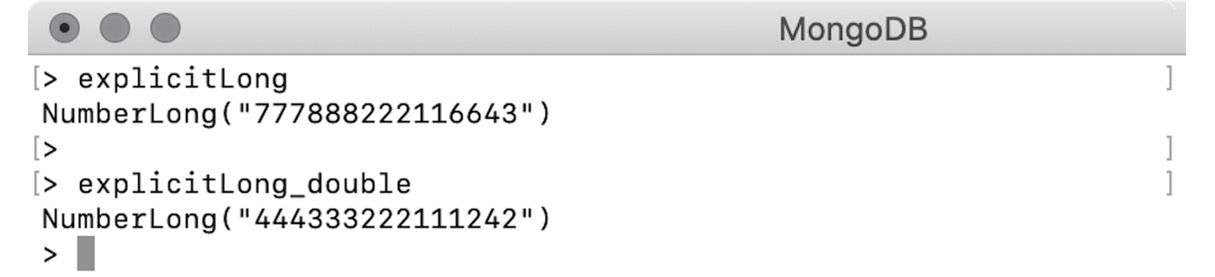

NumberLong: NumberLong wrappers are similar to NumberInt. The only difference is that they are stored as 64-bit integers. Let's try it on the shell:

> var explicitLong = NumberLong("777888222116643")

> var explicitLong_double = NumberLong(444333222111242)

Let's print the documents in the shell:

Figure 2.5: MongoDB shell output

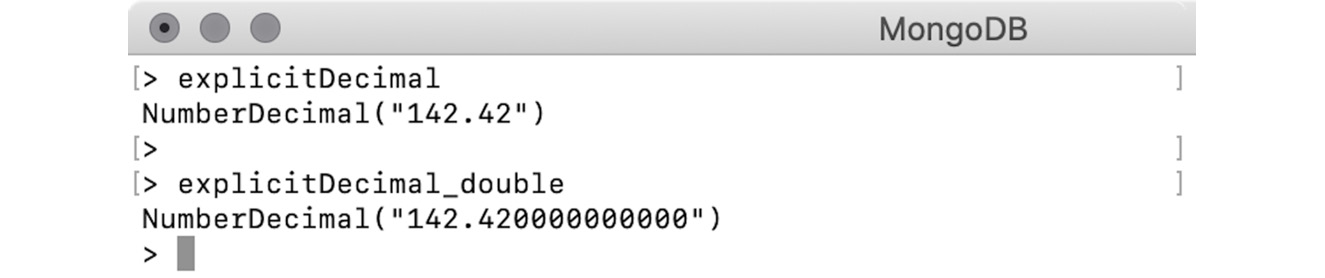

NumberDecimal: This wrapper stores the given number as a 128-bit IEEE 754 decimal format. The NumberDecimal constructor accepts both a string and a double representation of the number:

> var explicitDecimal = NumberDecimal("142.42")

> var explicitDecimal_double = NumberDecimal(142.42)

We are passing a string representation of a decimal number to explicitDecimal. However, explicitDecimal_double is created using a double. When we print the results, they appear slightly differently:

Figure 2.6: Output for explicitDecimal and explicitDecimal_double

The second number has been appended with trailing zeros. This is because of the internal parsing of the numbers. When we pass a double value to NumberDecimal, the argument is parsed to BSON's double, which is then converted to a 128-bit decimal with a precision of 15 digits.

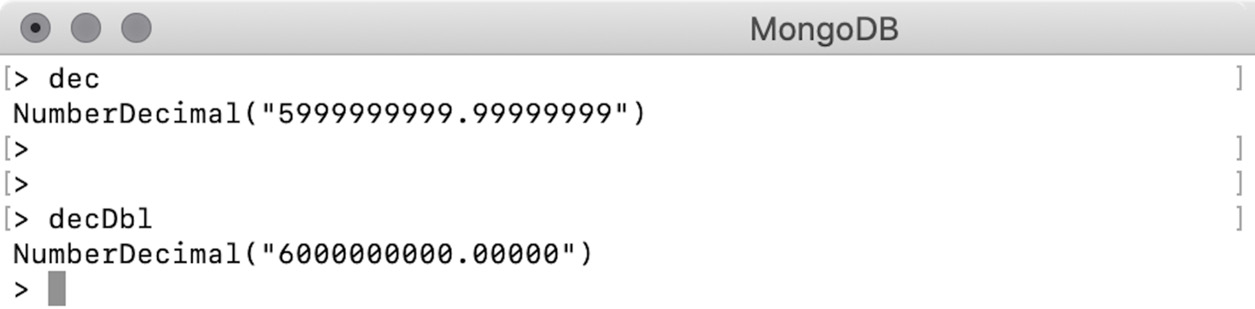

During this conversion, the decimal numbers are rounded off and may lose precision. Let's look at the following example:

> var dec = NumberDecimal("5999999999.99999999")

> var decDbl = NumberDecimal(5999999999.99999999)

Let's print the numbers and inspect the output:

Figure 2.7: Output for dec and decDbl

It is evident that when a double is passed to NumberDecimal, there is a chance of a loss of precision. Therefore, it is important to always use string-based constructors when using NumberDecimal.

The Boolean data type is used to represent whether something is true or false. Therefore, the value of a valid Boolean field is either true or false:

{

"isMongoDBHard": false

}

{

"amIEnjoying": true

}

The values do not have double quotes. If you wrap them in double quotes, they will be treated as strings.

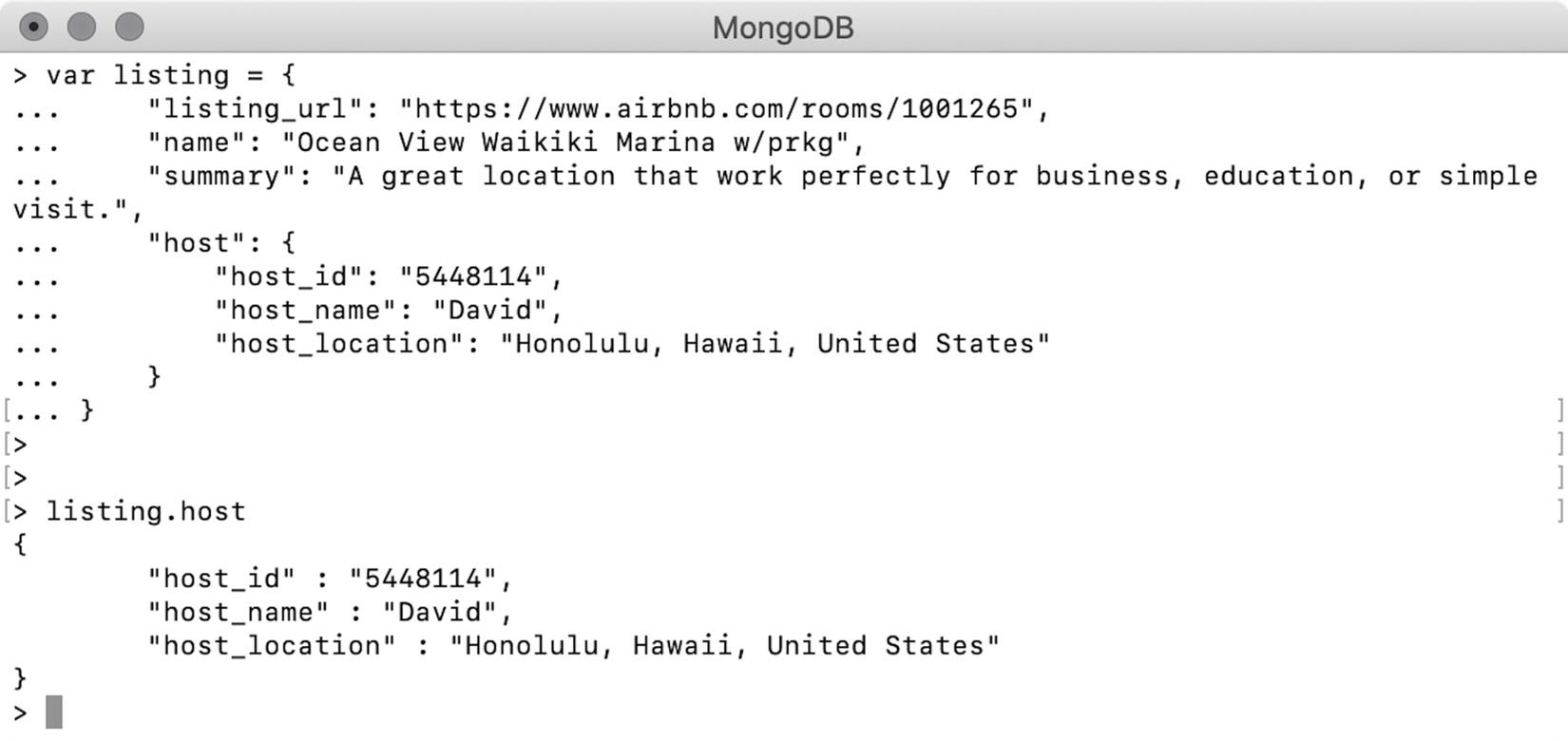

The object fields are used to represent nested or embedded documents—that is, a field whose value is another valid JSON document.

Let's take a look at the following example from the airbnb dataset:

{

"listing_url": "https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/1001265",

"name": "Ocean View Waikiki Marina w/prkg",

"summary": "A great location that work perfectly for business, education, or simple visit.",

"host":{

"host_id": "5448114",

"host_name": "David",

"host_location": "Honolulu, Hawaii, United States"

}

}

The value of the host field is another valid JSON. MongoDB uses a dot notation (.) to access the embedded objects. To access an embedded document, we will create a variable of the listing on the mongo shell:

> var listing = {

"listing_url": "https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/1001265",

"name": "Ocean View Waikiki Marina w/prkg",

"summary": "A great location that work perfectly for business, education, or simple visit.",

"host": {

"host_id": "5448114",

"host_name": "David",

"host_location": "Honolulu, Hawaii, United States"

}

}

To print only the host details, use the dot notation (.) to get the embedded object, as follows:

Figure 2.8: Output for the embedded object

Using a similar notation, you can also access a specific field of the embedded document as follows:

> listing.host.host_name David

Embedded documents can have further documents within them. Having embedded documents makes a MongoDB document a piece of self-contained information. To record the same information in an RDBMS database, you will have to create the listing and the host as two separate tables with a foreign key reference in between, and join the data from both tables to get a piece of information.

Along with embedded documents, MongoDB also supports links between the documents of two different collections, which resembles having foreign key references.

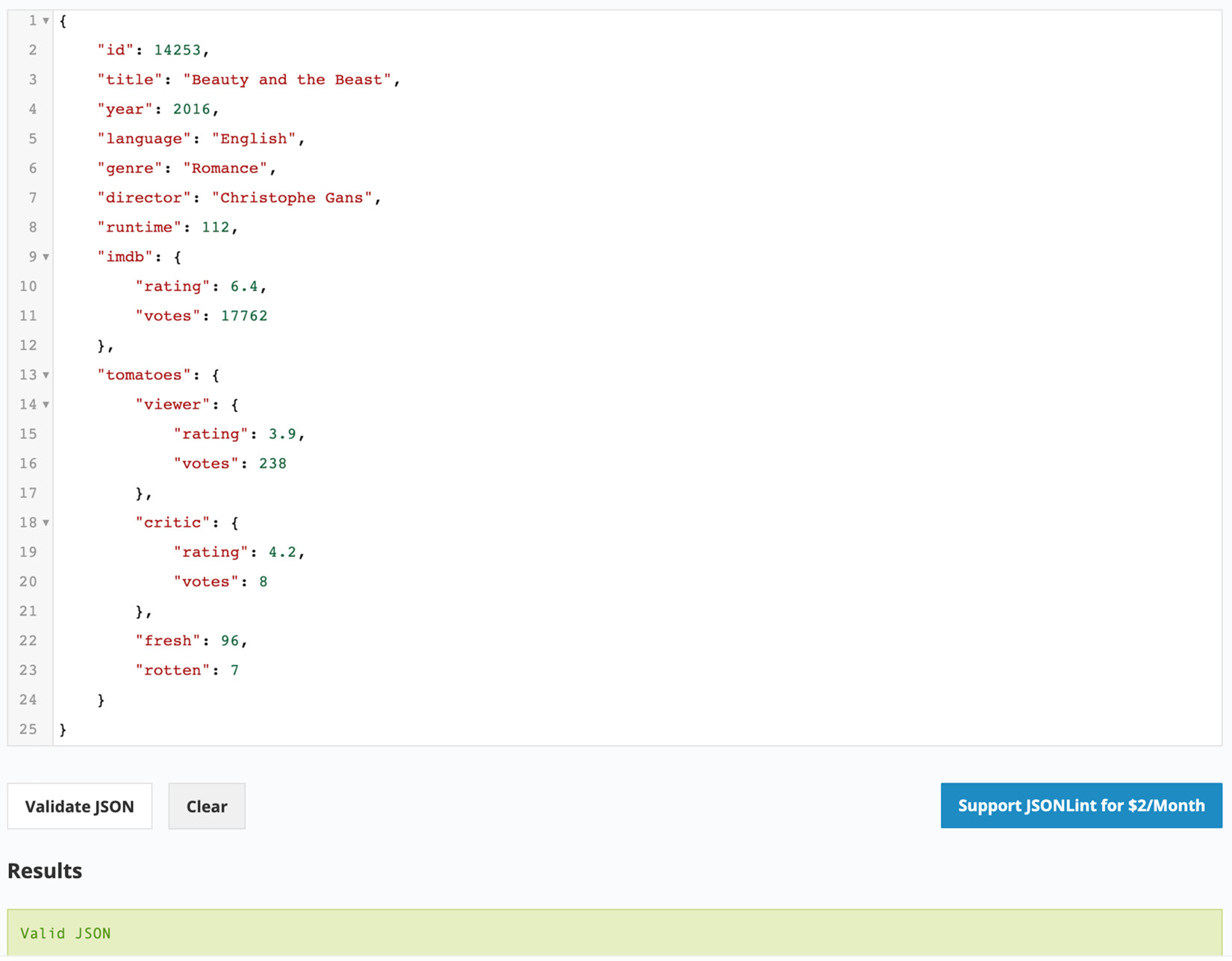

Your organization is happy with the movie representation so far. Now they have come up with a requirement to include the IMDb ratings and the number of votes that derived the rating. They also want to incorporate Tomatometer ratings, which include the user ratings and critics ratings along with fresh and rotten scores. Your task is to modify the document to update the imdb field to include the number of votes and add a new field called tomatoes, which contains the Rotten Tomato ratings.

Recall the JSON document of a sample movie record that you created in Exercise 2.01, Creating Your Own JSON Document:

{

"id": 14253,

"title": "Beauty and the Beast",

"year": 2016,

"language": "English",

"imdb_rating": 6.4,

"genre": "Romance",

"director": "Christophe Gans",

"runtime": 112

}

The following steps will help modify the IMDb ratings:

imdb_rating field indicates the IMDb rating score, so add an additional field to represent the vote count. However, both fields are closely related to each other and will always be used together. Therefore, group them together in a single document:{

"rating": 6.4,

"votes": "17762"

}imdb_rating field with the one you just created:{

"id" : 14253,

"Title" : "Beauty and the Beast",

"year" : 2016,

"language" : "English",

"genre" : "Romance",

"director" : "Christophe Gans",

"runtime" : 112,

"imdb" :

{

"rating": 6.4,

"votes": "17762"

}

}This imdb field with its value of an embedded object represents the IMDb ratings. Now, add the Tomatometer ratings.

Viewer Ratings and Critics Ratings will have a rating field and a votes field. Write these two documents separately:// Viewer Ratings

{

"rating" : 3.9,

"votes" : 238

}

// Critic Ratings

{

"rating" : 4.2,

"votes" : 8

}{

"viewer" : {

"rating" : 3.9,

"votes" : 238

},

"critic" : {

"rating" : 4.2,

"votes" : 8

}

}fresh and rotten scores as per the description:{

"viewer" : {

"rating" : 3.9,

"votes" : 238

},

"critic" : {

"rating" : 4.2,

"votes" : 8

},

"fresh" : 96,

"rotten" : 7

}The following output represents the Tomatometer ratings with the new tomatoes field in our movie record:

{

"id" : 14253,

"Title" : "Beauty and the Beast",

"year" : 2016,

"language" : "English",

"genre" : "Romance",

"director" : "Christophe Gans",

"runtime" : 112,

"imdb" : {

"rating": 6.4,

"votes": "17762"

},

"tomatoes" : {

"viewer" : {

"rating" : 3.9,

"votes" : 238

},

"critic" : {

"rating" : 4.2,

"votes" : 8

},

"fresh" : 96,

"rotten" : 7

}

}Validate JSON to validate the code:

Figure 2.9: Validation of the JSON document

Your movie record is now updated with detailed IMBb ratings and the new tomatoes rating. In this exercise, you practiced creating two nested documents to represent IMDb ratings and Tomatometer ratings. Now that we have covered nested or embedded objects, let's learn about arrays.

A field with an array type has a collection of zero or more values. In MongoDB, there is no limit to how many elements an array can contain or how many arrays a document can have. However, the overall document size should not exceed 16 MB. Consider the following example array containing four numbers:

> var doc = {

first_array: [

4,

3,

2,

1

]

}

Each element in an array can be accessed using its index position. While accessing an element on a specific index position, the index number is enclosed in square brackets. Let's print the third element in the array:

> doc.first_array[3] 1

Note

Indexes are always zero-based. The index position 3 denotes the fourth element in the array.

Using the index position, you can also add new elements to an existing array, as in the following example:

> doc.first_array[4] = 99

Upon printing the array, you will see that the fifth element has been added correctly, which contains the index position, 4:

> doc.first_array [ 4, 3, 2, 1, 99 ]

Just like objects having embedded objects, arrays can also have embedded arrays. The following syntax adds an embedded array into the sixth element:

> doc.first_array[5] = [11, 12] [ 11, 12 ]

If you print the array, you will see the embedded array as follows:

> doc.first_array [ 4, 3, 2, 1, 99, [11, 12]] >

Now, you can use the square notation, [], to access the elements of a specific index in the embedded array, as follows:

> doc.first_array[5][1] 12

The array can contain any MongoDB valid data type fields. This can be seen in the following snippet:

// array of strings

[ "this", "is", "a", "text" ]

// array of doubles

[ 1.1, 3.2, 553.54 ]

// array of Json objects

[ { "a" : 1 }, { "a" : 2, "b" : 3 }, { "c" : 1 } ]

// array of mixed elements

[ 12, "text", 4.35, [ 3, 2 ], { "type" : "object" } ]

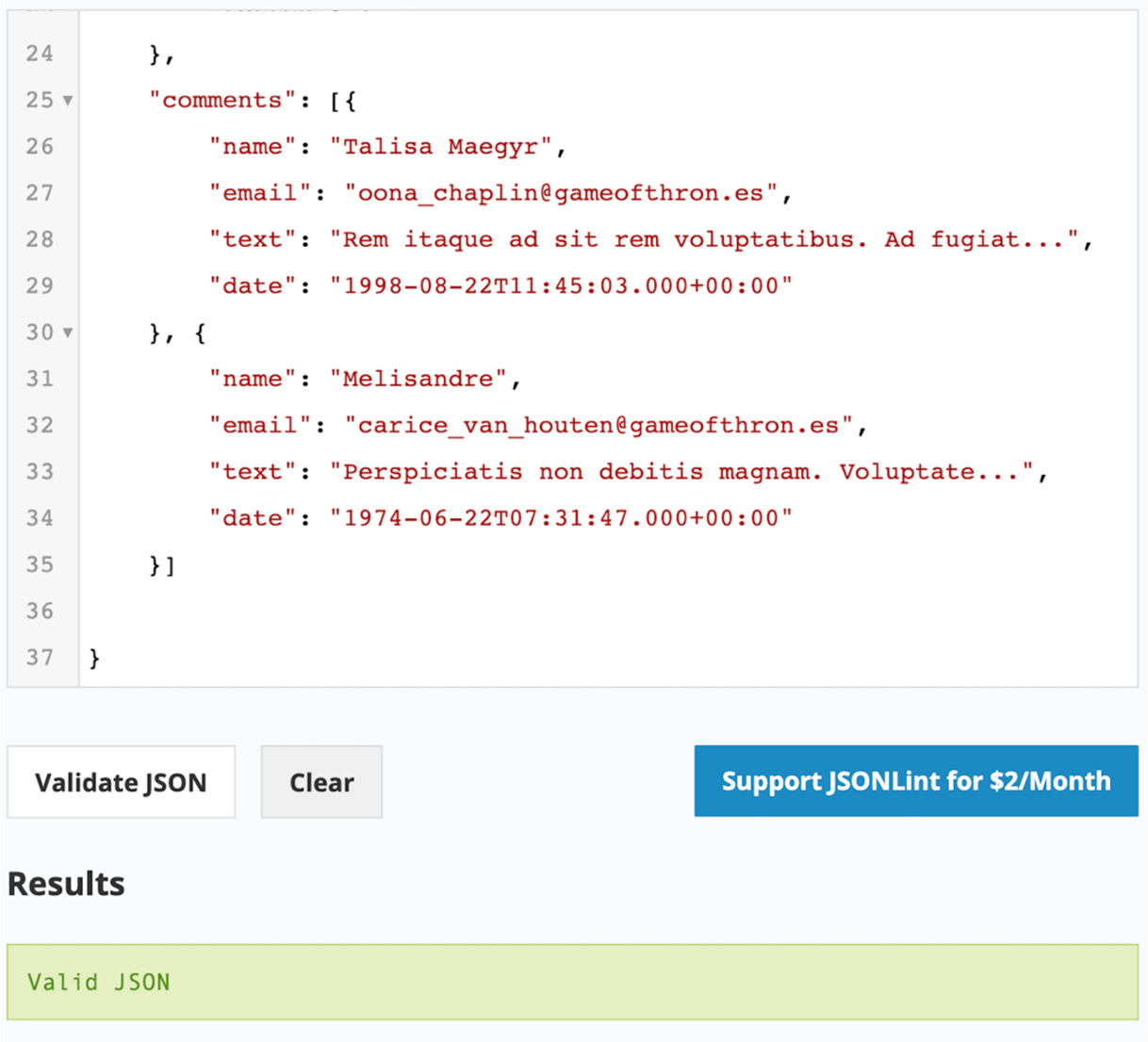

In order to add comment details for each movie, your organization wants you to include full text of the comment along with user details such as name, email, and date. Your task is to prepare two dummy comments and add them to the existing movie record. In Exercise 2.02, Creating Nested Objects, you developed a movie record in a document format, which looks as follows:

{

"id" : 14253,

"Title" : "Beauty and the Beast",

"year" : 2016,

"language" : "English",

"genre" : "Romance",

"director" : "Christophe Gans",

"runtime" : 112,

"imdb" : {

"rating": 6.4,

"votes": "17762"

},

"tomatoes" : {

"viewer" : {

"rating" : 3.9,

"votes" : 238

},

"critic" : {

"rating" : 4.2,

"votes" : 8

},

"fresh" : 96,

"rotten" : 7

}

}

Build upon this document to add additional information by executing the following steps:

// Comment #1 Name = Talisa Maegyr Email = [email protected] Text = Rem itaque ad sit rem voluptatibus. Ad fugiat... Date = 1998-08-22T11:45:03.000+00:00 // Comment #2 Name = Melisandre Email = [email protected] Text = Perspiciatis non debitis magnam. Voluptate... Date = 1974-06-22T07:31:47.000+00:00

Note

The comment text has been truncated to fit it on a single line.

// Comment #1

{

"name" : "Talisa Maegyr",

"email" : "[email protected]",

"text" : "Rem itaque ad sit rem voluptatibus. Ad fugiat...",

"date" : "1998-08-22T11:45:03.000+00:00"

}

// Comment #2

{

"name" : "Melisandre",

"email" : "[email protected]",

"text" : "Perspiciatis non debitis magnam. Voluptate...",

"date" : "1974-06-22T07:31:47.000+00:00"

}There are two comments in two separate documents, and you can easily fit them in the movie record as comment_1 and comment_2. However, as the number of comments will increase, it will be difficult to count their number. To overcome this, we will use an array, which implicitly assigns an index position to each element.

[

{

"name": "Talisa Maegyr",

"email": "[email protected]",

"text": "Rem itaque ad sit rem voluptatibus. Ad fugiat...",

"date": "1998-08-22T11:45:03.000+00:00"

},

{

"name": "Melisandre",

"email": "[email protected]",

"text": "Perspiciatis non debitis magnam. Voluptate...",

"date": "1974-06-22T07:31:47.000+00:00"

}

]An array gives you the opportunity to add as many comments as you want. Also, because of the implicit indexes, you are free to access any comment via its dedicated index position. Once you add this array in the movie record, the output will appear as follows:

{

"id": 14253,

"Title": "Beauty and the Beast",

"year": 2016,

"language": "English",

"genre": "Romance",

"director": "Christophe Gans",

"runtime": 112,

"imdb": {

"rating": 6.4,

"votes": "17762"

},

"tomatoes": {

"viewer": {

"rating": 3.9,

"votes": 238

},

"critic": {

"rating": 4.2,

"votes": 8

},

"fresh": 96,

"rotten": 7

},

"comments": [{

"name": "Talisa Maegyr",

"email": "[email protected]",

"text": "Rem itaque ad sit rem voluptatibus. Ad fugiat...",

"date": "1998-08-22T11:45:03.000+00:00"

}, {

"name": "Melisandre",

"email": "[email protected]",

"text": "Perspiciatis non debitis magnam. Voluptate...",

"date": "1974-06-22T07:31:47.000+00:00"

}]

}Validate JSON to validate the code:

Figure 2.10: Validation of the JSON document

We can see that our movie record now has user comments. In this exercise, we have modified our movie record to practice creating array fields. Now it is time to move on to the next data type, null.

Null is a special data type in a document and denotes a field that does not contain a value. The null field can have only null as the value. You will print the object in the following example, which will result in the null value:

> var obj = null > > obj Null

Build upon the array we created in the Arrays section:

> doc.first_array [ 4, 3, 2, 1, 99, [11, 12]]

Now, create a new variable and initialize it to null by inserting the variable in the next index position:

> var nullField = null > doc.first_array[6] = nullField

Now, print this array to see the null field:

> doc.first_array [ 4, 3, 2, 1, 99, [11, 12], null]

Every document in a collection must have an _id that contains a unique value. This field acts as a primary key to these documents. The primary keys are used to uniquely identify the documents, and they are always indexed. The value of the _id field must be unique in a collection. When you work with any dataset, each dataset represents a different context, and based on the context, you can identify whether your data has a primary key. For example, if you are dealing with the users' data, the users' email addresses will always be unique and can be considered the most appropriate _id field. However, for some datasets that do not have a unique key, you can simply omit the _id field.

If you insert a document without an _id field, the MongoDB driver will autogenerate a unique ID and add it to the document. So, when you retrieve the inserted document, you will find _id is generated with a unique value of random text. When the _id field is automatically added by the driver, the value is generated using ObjectId.

The ObjectId value is designed to generate lightweight code that is unique across different machines. It generates a unique value of 12 bytes, where the first 4 bytes represent the timestamp, bytes 5 to 9 represent a random value, and the last 3 bytes are an incremental counter. Create and print an ObjectId value as follows:

> var uniqueID = new ObjectId()

Print uniqueID on the next line:

> uniqueID

ObjectId("5dv.8ff48dd98e621357bd50")

MongoDB supports a technique called sharding, where a dataset is distributed and stored on different machines. When a collection is sharded, its documents are physically located on different machines. Even so, ObjectId can ensure that the values will be unique in the collection across different machines. If the collection is sorted using the ObjectId field, the order will be based on the document creation time. However, the timestamp in ObjectId is based on the number of seconds to epoch time. Hence, documents inserted within the same second may appear in a random order. The getTimestamp() method on ObjectId tells us the document insertion time.

The JSON specifications do not support date types. All the dates in JSON documents are represented as plain strings. The string representations of dates are difficult to parse, compare, and manipulate. MongoDB's BSON format, however, supports Date types explicitly.

The MongoDB dates are stored in the form of milliseconds since the Unix epoch, which is January 1, 1970. To store the millisecond's representation of a date, MongoDB uses a 64-bit integer (long). Because of this, the date fields have a range of around +/-290 million years since the Unix epoch. One thing to note is that all dates are stored in UTC, and there is no time zone associated with them.

While working on the mongo shell, you can create Date instances using Date(), new Date(), or new ISODate():

Note

Dates created with a new Date() constructor or a new ISODate() constructor are always in UTC, and ones created with Date() will be in the local time zone. An example of this is given next.

var date = Date()// Sample output Sat Sept 03 1989 07:28:46 GMT-0500 (CDT)

When a Date() type is used to construct a date, it uses JavaScript's date representation, which is in the form of plain strings. These dates represent the date and time based on your current time zone. However, being in string formats, they are not useful for comparison or manipulation.

If you add the new keyword to the Date constructor, you get the BSON date that is wrapped in ISODate() as follows:

> var date = new Date()

// Sample output

ISODate("1989-09-03T10:11:23.357Z")

You can also use the ISODate() constructor directly to create date objects as follows:

> var isoDate = new ISODate()

// Sample output

ISODate("1989-09-03T11:13:26.442Z")

These dates can be manipulated, compared, and searched.

Note

As per the MongoDB documentation, not all drivers support 64-bit date encodings. However, all the drivers support encoding dates having the year ranging from 0 to 9999.

The timestamp is a 64-bit representation of date and time. Out of the 64 bits, the first 32 bits store the number of seconds since the Unix epoch time, which is January 1, 1970. The other 32 bits indicate an incrementing counter. The timestamp type is exclusively used by MongoDB for internal operations.

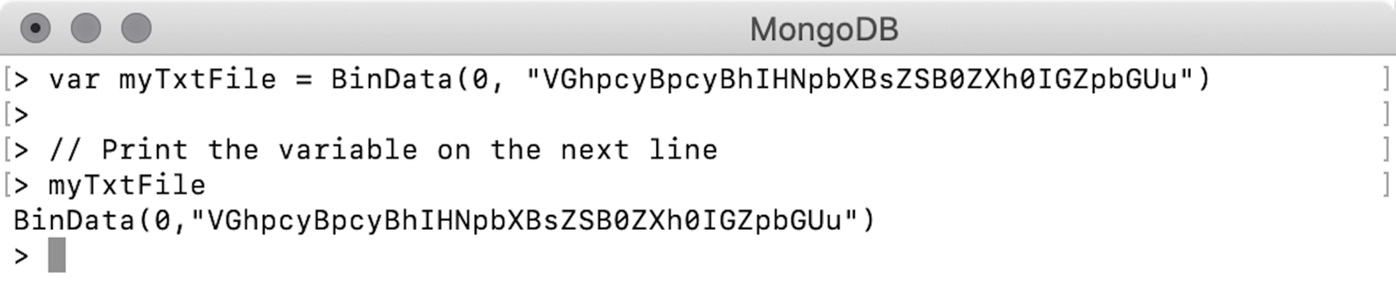

Binary data, also called BinData, is a BSON data type for storing data that exists in a binary format. This data type gives you the ability to store almost anything in the database, including files such as text, videos, music, and more. BinData can be mapped with a binary array in your programming language as follows:

Figure 2.11: Binary array

The first argument to BinData is a binary subtype to indicate the type of information stored. The zero value stands for plain binary data and can be used with text or media files. The second argument to BinData is a base64-encoded text file. You can use the binary data field in a document as follows:

{

"name" : "my_txt",

"extension" : "txt",

"content" : BinData(0,/

"VGhpcyBpcyBhIHNpbXBsZSB0ZXh0IGZpbGUu")

}

We will cover MongoDB's document size limit in the upcoming section.

Change the font size

Change margin width

Change background colour