For all of our visual programming examples, we will be typing them in pseudo-code for easier understanding. This code will not work, but it will give you an idea about the concepts of programming. So, let's use an example of moving something to the right. The code might look something like the following line of code:

This works, but we haven't set up a speed for the object. Right now, either the default speed will be the speed of the object and the object will move too fast for the human eye to see, or the compiler might get an error. If you misspell a word or make some kind of syntax error, the game might not run. So, we might have to update our code as follows:

Notice how there is a semicolon at the end of each line. The semicolon tells the computer to read the next line. However, if you look at the code, we haven't told the computer to check for a button being pressed. If we add that code, it might be something similar to the following code:

As per the preceding line of code, if the right arrow is pressed then the GameObject will move to the right. This is called an if statement, and all it does is check for a condition to be true. In this case, if the right arrow is pressed then the GameObject will move to the right; however, if the right arrow is not pressed then nothing will happen. Now, let's add the logic for the left arrow being pressed. The code is as follows:

We should mention at this point that there are only two lines of code in these if statements, but there can be many more. Imagine how gigantic the code base is for some of the games you play. Those games are much more complex. Sometimes, the logic for the right arrow being pressed can be more than a page of logic. Let's add some code that will make the GameObject move in four directions. The code is as follows:

This is a lot of code and we are not even making a complex game. So far, our game just has a GameObject moving up, down, left, and right. We have no projectiles, no antagonists, and no artificial intelligence. So, why a code like this? Well, it's only recently that non-coding languages have been around. If you have ever played a game, it was painstakingly coded. We should also point out that the preceding code is an abbreviated version to make it simpler. Depending on the language, moving something across the screen might take many more lines of code.

Working with visual programming languages

Visual programming languages do exactly the same thing that regular programming languages do, except that all of the logic is placed visually. This is more efficient for several reasons:

- You can layout information in different areas

- Logic that would take multiple lines of code can be in one dialog box

- You can visually see that your game is coming together

At this point, we should also mention that, in most game development environments, you have to do most of the work by typing commands. Having an editor where you visually assemble your game, even if it is just the level design, wasn't always the case. One of the best features of a visual programming language is that you can see everything and test everything much more easily than traditional game development environments.

In Construct 2, we have two main areas in which we work. The first area is called the layout, which is a visual representation of what the game will look like when a player plays it. In this area, we can perform the following actions:

- Drop in all of our game objects so that we can arrange them the way we like

- Set the look of the game

- Add the heads-up display (HUD) and other Graphic User Interface (GUI) elements

The following screenshot shows the layout with some game objects on it:

Each game object is a sprite. A sprite can have an image, an animation (multiple images), and a game logic attached to it. Your event sheet will look like the following screenshot:

The second area is the event sheet. An event sheet is where the game logic goes. This is where we would "code" the game in other environments (see the preceding image).

If we want to add some logic so that the game characters will move left and right, this is where we will add it. Right now, there is nothing in our event sheet; however, we can go and add something to demonstrate how we will "code" in the game logic.

To add an event, all you have to do is click on the Add event button. Another way of adding an event is to just double-click on the area underneath the Event sheet 1 tab, as shown in the following screenshot:

The Add event dialog box will provide you with all of the possible game objects and commands you can use in your game.

As you can see in the Layout1 window, all the game objects in the game are here. You will also see a system icon. This icon brings up the internal commands and functional commands that you can use.

If we want to select the sprite to move forward, we can simply select the sprite and give it a command. Remember, in other environments, you would have to type that in. If we want to make the sprite move left with the A button, we can simply select the A button and add some logic that would make the sprite move left, as shown in the following screenshot:

You will also notice that all of the game objects are properly named. It is very important to name all of your game objects appropriately. When your game has a few hundred game objects, it will become much easier to manage if your game objects are named properly.

Let's go ahead and select the sprite by double-clicking on it. Once you do this, you will be able to see a bunch of conditions. These conditions must be met before we give an action to perform. In the same way as the if statement we looked at a few pages ago, we need to make sure a condition is true; only then we can go ahead and add an action. The Add event window should look like the following screenshot:

Now, let's scroll down and select Is on-screen as shown in the following screenshot:

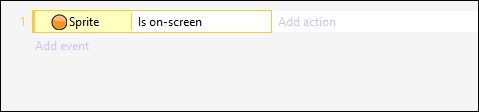

As you can see, once you select Is on-screen, the onscreen condition is added to the event sheet. You can also see that you can add an action and another event. We want the sprite to do something before we move on.

If you click on

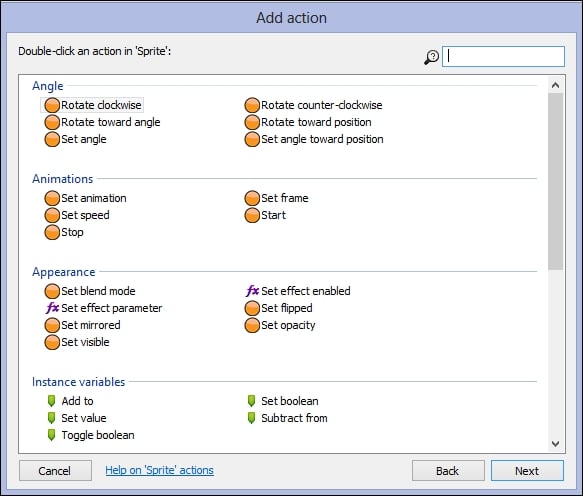

Add action, you will get a similar dialog box but with actions instead of conditions. Let's go ahead and click on the Sprite element and the following screen will pop up:

You will see actions that you can add to the sprite, as shown in the preceding screenshot. Take a moment to look at all of the actions and you can see how versatile Construct 2 really is.

Once you have finished looking, go ahead and click on Rotate clockwise. This will make the sprite rotate. You can enter in any number in the Degrees textbox:

Let's look at what we are telling the computer to do. While the condition of the sprite is onscreen, the action will be to rotate the sprite. If we were to run the game, the sprite will rotate. This may seem like it is really simple, but imagine if you had to code all of that by typing in commands. It would take a very long time. What we have just shown you is the power of visual programming languages. They take out most of the work needed to develop games. Instead, you can focus on creativity and design versus technicality.

Free Chapter

Free Chapter