Creating your first managed package

Packages and subsequent versions are created using Salesforce DX CLI commands. The steps to be performed are:

- Setting your package namespace

- Creating the package and assigning it to the namespace

- Adding components to the package

Not all aspects of the Salesforce Platform can be packaged. To help ensure you are fully aware of what is supported and what is not, Salesforce has created an interactive report known as the Salesforce Metadata Coverage report. This can be found here: https://developer.salesforce.com/docs/metadata-coverage.

These steps will be discussed in the following sections.

Setting and registering your package namespace

An important decision when creating a managed package is the namespace; this is a prefix applied to all your components (Custom Objects, Apex code, Lightning Components, and so on) and is used by developers in subscriber orgs to uniquely distinguish between your packaged components and others, even those from other packages. The namespace prefix is an important part of the branding of the application since it is implicitly attached to any Apex code or other components that you include in your package.

The namespace can be up to 15 characters, though I personally recommend that you keep it to less than this, as it becomes hard to remember and leads to frustrating typos if you make it too complicated. I would also avoid the underscore character. It is a good idea to have a naming convention if you are likely to create more managed packages in the future. The following is the format of an example naming convention:

[company acronym - 1 to 4 characters][package prefix 1 to 4 characters]

For example, if ACME was an ISV, the ACME Corporation’s Road Runner application might be named acmerr. You may want to skip prefixing with your company acronym when considering a namespace for an application package internal only to your business.

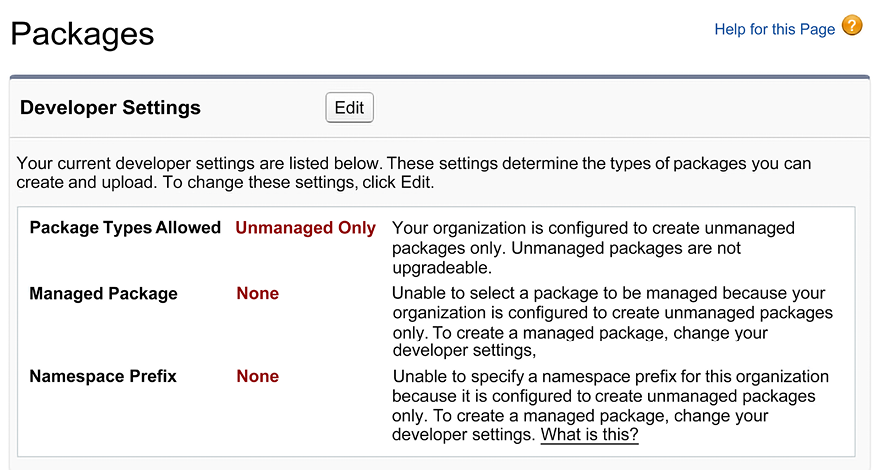

Log in to the namespace org discussed earlier in this chapter. Navigate to the Packages page (accessed under the Setup menu, under the Create submenu). Click on the Edit button to begin a short wizard to enter your desired namespace. This can only be done once and must be globally unique (meaning it cannot be set in any other org), much like a website domain name.

Assigning namespaces

For the purposes of following along with this book, please feel free to make up any namespace you desire; for example, fforce{yourinitials}. Do not use one that you may plan to use in the future, since once it has been assigned, it cannot be changed or reused.

The following screenshot shows the Packages page:

Figure 1.3: Packages page accessed from the Setup menu

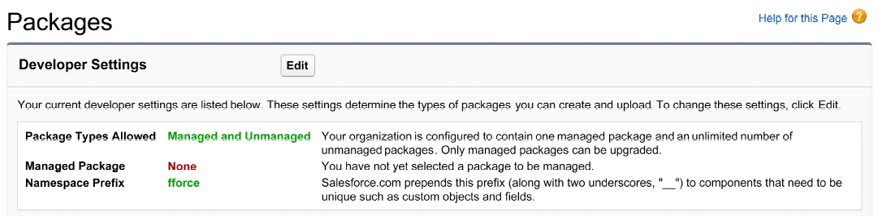

Once you have set the namespace, the preceding page should look like the following screenshot, with the difference being that it is now showing the namespace prefix that you have used and that managed packages can now also be created. You are now ready to create a managed package and assign it to the namespace:

Figure 1.4: Packages page after setting the namespace

You can now log out from the namespace org – it is no longer needed from this point on. Log in to your Dev Hub org and register your namespace with Salesforce DX. This allows you to create scratch orgs that use that namespace, allowing you to develop your application in a way that more closely represents its final form. Salesforce provides an excellent guide on registering your namespace at https://developer.salesforce.com/docs/atlas.en-us.sfdx_dev.meta/sfdx_dev/sfdx_dev_reg_namespace.htm.

Creating the package and assigning it to the namespace

Return to VSCode and edit your sfdx-project.json file to reference the namespace:

{

"packageDirectories": [

{

"path": "source/formulaforce",

"default": true

}

],

"namespace": "fforce",

"sfdcLoginUrl": "https://login.salesforce.com",

"sourceApiVersion": "56.0"

}

The sample code associated with each chapter of this book does not reference any namespace in the sfdx-project.json file. If you want to continue using your namespace after you have refreshed your project for a given chapter, you must repeat the preceding edit with your own namespace. It is generally good practice to develop using the namespace of your package as it is closer to the final installed state of your code and thus will ensure any bugs related to namespace handling are identified earlier.

To create your package and register it with your Dev Hub, run the following command:

sfdx force:package:create

--name "FormulaForce App"

--description "FormulaForce App"

--packagetype Managed

--path force-app

Once the command completes, review your sfdx-project.json file again; it should look like the example that follows. In the following example, the ID starting with 0Ho will vary:

{

"packageDirectories": [

{

"path": "source/formulaforce",

"default": true,

"package": "FormulaForce App",

"versionName": "ver 0.1"

"versionNumber": "0.1.0.NEXT",

"versionDescription": "FormulaForce"

}

],

"namespace": "fforce",

"sfdcLoginUrl": "https://login.salesforce.com",

"sourceApiVersion": "56.0",

"packageAliases": {

"FormulaForce App": "0Ho6A000000CaVxSAK"

}

}

Salesforce DX records your package and package version IDs here with aliases that you can edit or leave as the defaults. These aliases are easier to recall and understand at a glance when using other Salesforce CLI commands relating to packages. For example, the sfdx force:package:install CLI command supports an ID or an alias.

Adding components to the package

In this book, the contents of your project’s /source/formulaforce package directory folder will become the source of truth for the components that are included in each release of your package. The following layout shows what your application should look like in source file form so far:

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── config

│ └── project-scratch-def.json

├── sfdx-project.json

└── source

└── formulaforce

└── main

├── layouts

│ ├── Contestant__c-Contestant\ Layout.layout-meta.xml

│ ├── Driver__c-Driver\ Layout.layout-meta.xml

│ ├── Race__c-Race\ Layout.layout-meta.xml

│ └── Season__c-Season\ Layout.layout-meta.xml

└── objects

├── Contestant__c

│ ├── Contestant__c.object-meta.xml

│ └── fields

│ ├── Driver__c.field-meta.xml

│ └── Race__c.field-meta.xml

├── Driver__c

│ └── Driver__c.object-meta.xml

├── Race__c

│ ├── Race__c.object-meta.xml

│ └── fields

│ └── Season__c.field-meta.xml

└── Season__c

└── Season__c.object-meta.xml

You can consider creating multiple dependent packages from within one project by using different package directory folders for each package. Each package can share the same namespace or choose another. By default, code is not visible between packages unless you explicitly mark it as global, a concept discussed later in this book. To make code accessible only between your own packages (sharing the same namespace) and not your customers, use the @namespaceAccessible annotation rather than the global keyword. We will discuss dependent packages later in this chapter.

To create the first release of your package, run the following command (all on one line):

sfdx force:package:version:create

--package "FormulaForce App"

--definitionfile config/project-scratch-def.json

--wait 10 –– installationkeybypass

--codecoverage

Some things to note about the previous command line parameters are as follows:

- The

--packageparameter uses the package alias as defined in thesfdx-project.jsonfile to identify the package we are creating this version against. You can avoid using this attribute if you applydefault: trueto the package as defined in thesfdx-project.jsonfile. - The

--waitparameter ensures that you take advantage of the ability of the command to update yoursfdx-project.jsonfile with the ID of the package version. --installationkeypassis needed to ensure you agree to the fact that the package can be installed by anyone that has the ID. For your real applications, you may want to include a password if you feel there is a risk of this information being exposed.--codecoverageis needed to calculate the minimum of 75% code coverage in order to promote this package to release status. Even though there is no code in the package at this point, this flag is still required. If you are creating a package version only for beta testing purposes, this flag is not required, however, you will not be able to promote the package version to the Release status required to install the package in customers’ or your own production orgs. Beta and Release package types are discussed later in this chapter in more detail.

At this stage in the book, we have simply added some Custom Objects, so the process of creating the package should be completed reasonably quickly. Once the preceding command completes, your sfdx-project.json file should look like the following. Again, the IDs will vary from the ones shown here – each time you create a new version of your package, it will be recorded here:

{

"packageDirectories": [

{

"path": "source/formulaforce",

"package": "FormulaForce App",

"versionName": "ver 0.1",

"versionNumber": "0.1.0.NEXT",

"versionDescription": "FormulaForce App",

"default": true

}

],

"namespace": "fforce",

"sfdcLoginUrl": "https://login.salesforce.com",

"sourceApiVersion": "55.0",

"packageAliases": {

"FormulaForce App": "0Ho6A000000CaVxSAK",

"FormulaForce [email protected]": "04t6A0000038K3GQAU"

}

}

The NEXT keyword is used in the preceding versionNumber configuration to automatically assign a new version number each time a new package version is created.

Dependent packages

As their name suggests, dependent packages extend or add to the functionality delivered by the existing packages they are based on, though they cannot change the base package contents. They can extend one or more base packages, and you can even have several layers of extension packages, though you may want to keep an eye on how extensively you use this feature, as managing inter-package dependency can get quite complex, especially during development and deployment when using features such as Push Upgrade.

If you want to use dependent packages to control access to features of your application you want to sell as add-ons, for example, then you might want to consider the Feature Management feature. In this case, you would still package all of your application in one package but selectively hide parts of it through Feature Parameters.

Dependent packages are created in much the same way as the process you’ve just completed, except that you must define the dependent package in the sfdx-project.json file (shown as follows) and ensure the scratch org has those base packages installed in it before use. The following is an example sfdx-project.json file showing a package dependency for a new dependent package that is currently in development:

{

"packageDirectories": [

{

"path": "source/formulaforceaddons",

"package": "FormulaForce - Advanced Analytics Addon",

"default": true,

"dependencies": [

{

"package": "FormulaForce [email protected]"

}

]

}

],

"namespace": "fforce",

"sfdcLoginUrl": "https://login.salesforce.com",

"sourceApiVersion": "56.0",

"packageAliases": {

"FormulaForce [email protected]": "04t6A012003AB3GQAU"

}

}

The project containing the preceding example configuration only contains the dependent package components, since there is only one packageDirectories entry. In this case, the base package is developed in a separate project. However, as noted earlier, you can have multiple packages within a single Salesforce project. This does have the benefit of being able to work on both base and dependent packages together in one scratch org. However, it requires more careful management of the default package directory setting when performing synchronization operations. As shown later in this chapter, you can manually install any package in a scratch org, either via the browser with the package install URL or via the SFDX CLI. If a package takes a long time to install and configure, you may want to consider using the Scratch Org Snapshots feature, especially if you are building a CI/CD pipeline, as described later in this book, in Chapter 14, Source Control and Continuous Integration. Typically, a scratch org is empty when you create it; however, with this feature, you can have it include pre-installed base packages and related configuration or data.

As the code contained within dependent packages makes reference to other Custom Objects, Custom field, Apex code, and so on that are present in base packages, the platform tracks these dependencies and the version of the base package present at the time the reference was made. When an dependent package is installed, this dependency information ensures that the installation org has the correct version (minimum) of the base packages installed before permitting the installation of the dependent package to complete.

The preceding sections have described the package creation process, including the ability to create other dependent packages to allow you to deploy parts of your application that are applicable to only a subset of your customers, for example, for a given market. The following sections introduce concepts that require more understanding before you release your package to your target customers. Some of these things cannot be reverted.