What is a spotting session?

Given the same script, two different film directors would likely create quite different versions of a scene of a film. So, too, would two film composers likely score a scene differently. Both film directors and film composers bring their unique creativity to a project; however, collaboration and clear communication are essential to realizing a creative outcome in which the composer’s score seamlessly supports the film director’s vision. The film director and film composer must find a common artistic language to envision what a film needs. This often begins with what is called a spotting session.

Understanding spotting sessions

A spotting session is a meeting where the director and composer (though others can be involved too) determine and agree on what type of music will need to be composed and where the music will need to be placed within the movie timeline.

The composer’s task is to translate the emotional aspects of scenes into the music of the film score. This “translation,” though, must fit into the director’s overall vision. It can be counterproductive for the composer to make any decisions related to the score before they understand what the director is seeking. Without such understanding, the composer is shooting in the dark. This can lead to a lot of time spent on music that doesn’t support the director’s true vision and, therefore, is a waste of time. This is why the spotting session is so important.

Before the meeting

Before the meeting, the film editor and/or film director preselects existing music, called the temp track or temp music. This music gives them an idea of what they’re looking for or what the film may need before they meet with the film composer.

Temp music is not normally a film composer’s first choice because they have to emulate the audio examples to the point of nearly copying the temp track, instead of being able to create their own new and fresh score. This is an additional challenge for the film composer. What makes it more challenging is that the film composer needs to have the skill to follow the director’s request, retain the feel and the style of the temp music, and, at the same time, compose an original score.

The film composer will be sent a movie file with the temp track attached to it before the first spotting session. It is helpful to know your computer system so that you can ask the director or video editor to provide you with a movie file based on your computer system.

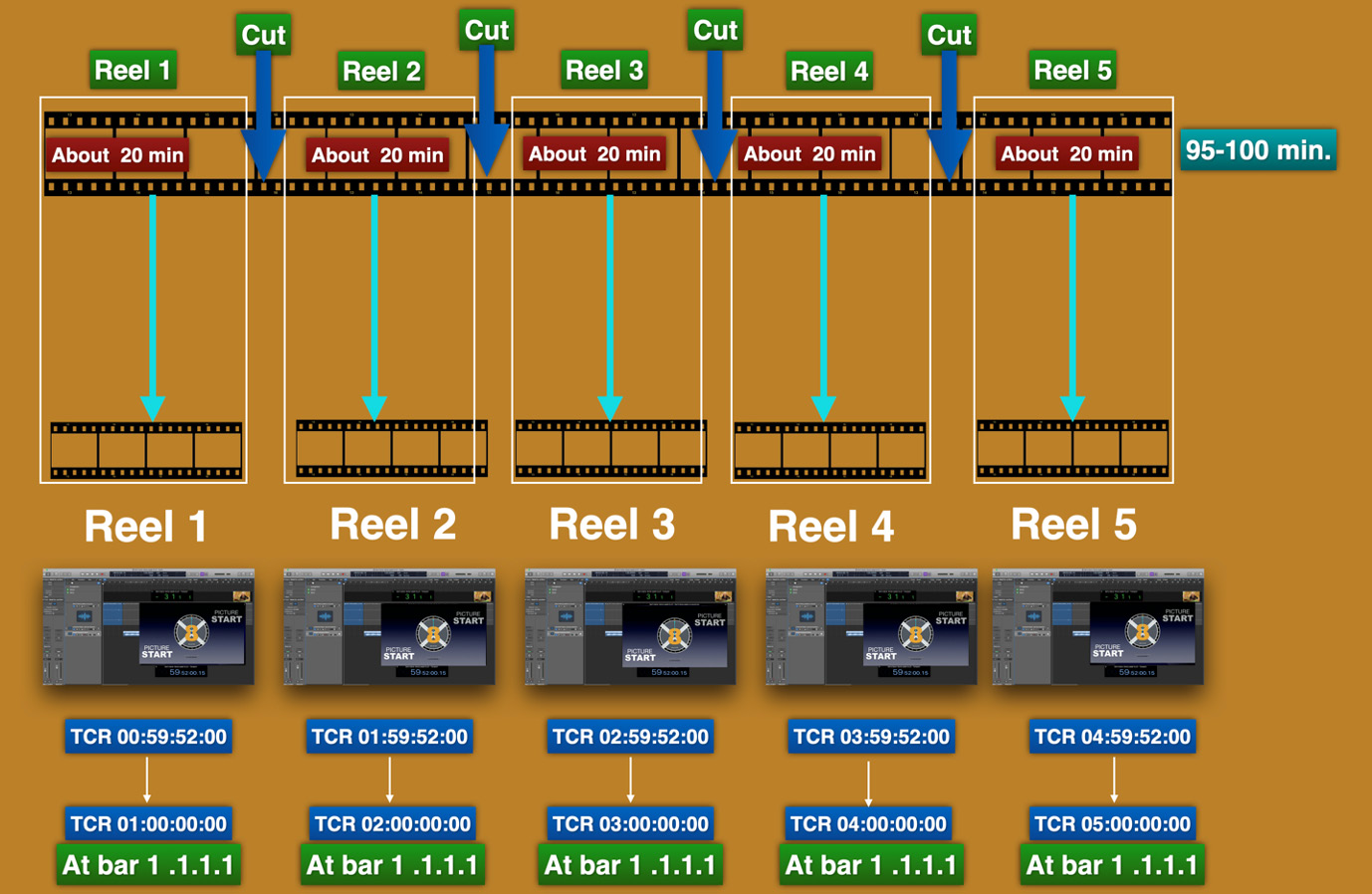

Since working in small movie chunks is more efficient, today, film directors and composers have found a way to work with one another by cutting the entire movie file into so-called reels. Take a look at the following diagram:

Figure 1.1: Film reels

So, if you are scoring 95-100 minutes of film, for example, you may want to ask the film director to cut the footage about every 20 minutes or so. The film director, however, makes the cuts based on the events and the story flow in the film, so they will not cut the reel in the middle of the story. In this example, you would end up with five reels in total.

In the case of a 60-minute film, you can request the director to cut the movie into 3 reels of 20 minutes each. You will work on one reel at a time. When you start composing to picture, you might end up with many different cues (or music pieces) inside the reel. Each cue might have a different revision until the director is completely satisfied with your score. Once the director is completely satisfied with each cue within the reel, including all the final revisions, and they’ve been approved, then you will move on to the next reel.

Next, we will examine how a film director or editor shares their notes on temp music and the directions that the film composer will need to follow.

Spotting notes

Spotting notes, also commonly known as cue sheets, are a list of important film cuts and descriptions that discuss the type of music that the film director is looking for. Cuts are also known as hit points, or spots where music needs to line up with important events in the film.

These spotting notes or cue sheets may or not be provided by the film director, depending on how the film company likes to work, but film composers will always have to make notes. If the film director doesn’t provide the written notes ahead of time, either way, the film composer will have to make notes during the spotting session meeting.

The following figure shows an example of some spotting notes:

Figure 1.2: Cue sheet example

This cue sheet example presents a general idea of what type of information should be included at a minimum (some cue sheets may be more elaborate or different based on what film company you are working with).

As we learned earlier, a feature film can be divided into, for example, five reels. In the preceding cue sheet example, in the Cue column, you can see a description of 1m1. Here, the first number represents the reel, m stands for music, and the second number represents the cue. So, 1m1 means reel one, music cue one; 1m2 means reel one, music cue two; and so forth.

The list of time codes in the Time Code In and Time Code Out columns is where the music should start and end for each cue. Time codes will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

For each music cue, you should know what the director’s intentions are. The fourth column, Music Description/Mood, describes what the music’s intended feel/mood should be at specific points in the film. Since most film directors are not familiar with music terminology, they will tell you what they want via emotions or feelings they want to evoke, or what style and genre of music they want. This is often discussed during the meeting.

During the meeting

During the spotting session, both the film composer and director watch the film together, go through the spotting notes, and talk about the film director’s vision for the film and the role that the music will play in it. This is an important time for you to ask as many questions as you need to understand the director’s vision and get the job done.

In the meeting, you will open a movie file that should be synced in Logic Pro, along with the burnt-in timecode (BITC) window that the editor will give you so that you can make specific notes about the film’s events. The film director will point to a specific timecode location and, from that, you will write a specific music cue.

In the following BITC example, you can see that the window shows TC 01:00:00:00. TC stands for timecode, the first two numbers refer to hours, the next two for minutes, followed by seconds, and then frames. So, if the director asks for the music to start at this timecode, they are asking for music to start exactly at the 1 hour, 0 minutes, 0 seconds, 0 frames mark:

Figure 1.3: Movie with BITC example 1

As another example, the director may ask you to write music 13 seconds into the film. This would be reflected by a timecode of TC 01:00:13:00 – that is, 1 hour, 0 minutes, 13 seconds, 0 frames:

Figure 1.4: Movie with BITC example 2

Without the timecode window in the movie, you will not know whether your DAW is synced to the picture. This process will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

The process of reviewing spotting notes might also involve looking at the provided temp track list from the cue sheet. The two of you will likely consider questions such as the following:

- Where should music be playing and where should there be silence?

- What should the music be doing in this or that scene?

- What does the director want the audience to feel?

The film director will use mood descriptions, also referred to as buzzwords, instead of musical terms to describe how they want the music to be. For example, they may ask you to compose music that is magical and, at the same time, mysterious. For reference, the following chart lists some commonly used mood descriptions:

Figure 1.5: Moods in film music

The film director may also send you additional YouTube links as examples, to help describe the mood, and you should include those in the Reference/Temp Music column (shown in Figure 1.2). The film composer should take notes of these descriptions while reviewing the film.

Using music to convey complex emotions while using moods

Expressing moods in music composition can be challenging – the film composer has to use the music to convey a very complex set of emotions to the audience, in a way that is effective yet subtle, and that does not draw too much attention to itself. If the music is too obvious, the score is no longer effective, and the audience will be focusing on the music rather than the story.

The composer uses tools such as musical instruments, sample libraries, and recording equipment to reflect the emotional state of a character or scene in support of the underlying drama. The film score can greatly deepen the visual experience by providing “the right sound” that triggers emotions in the viewers. It helps viewers absorb all of what a complex scene presents.

When watching a movie, have you noticed that when the main character appears, a specific musical phrase will play each time they appear? Each main character can have a musical theme known as a leitmotif (this comes from a German term that means “leading motive”). Think of the menacing music that plays when Darth Vader appears in Star Wars. That signature sound or so-called leitmotif helps the audience identify characters with ease amid sound effects, dialogue, action, the main score, and more.

End of the meeting

The end of the meeting is a good time to ask the director how the final score needs to be delivered. This means either scoring using a computer (commonly referred to as “in the box”) or utilizing a live orchestra. Scoring “in the box” is relatively inexpensive compared to a live orchestral session. The director’s choice, based on the film production’s budget, will determine the outcome.

Now that we’ve discussed the spotting session and how the composer will know exactly what the music needs to do, next, we’ll talk about what character traits will greatly impact the quality of your work.