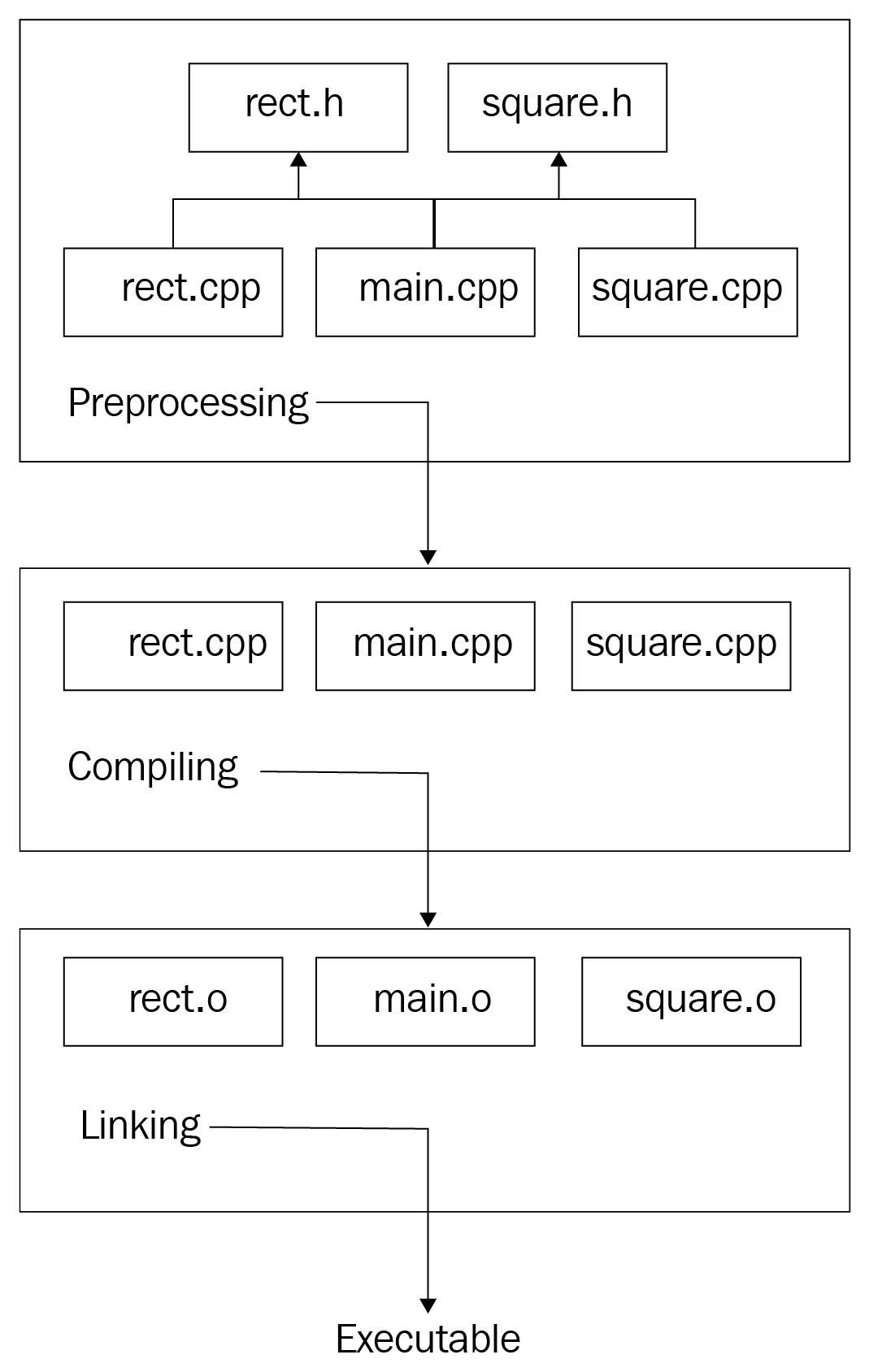

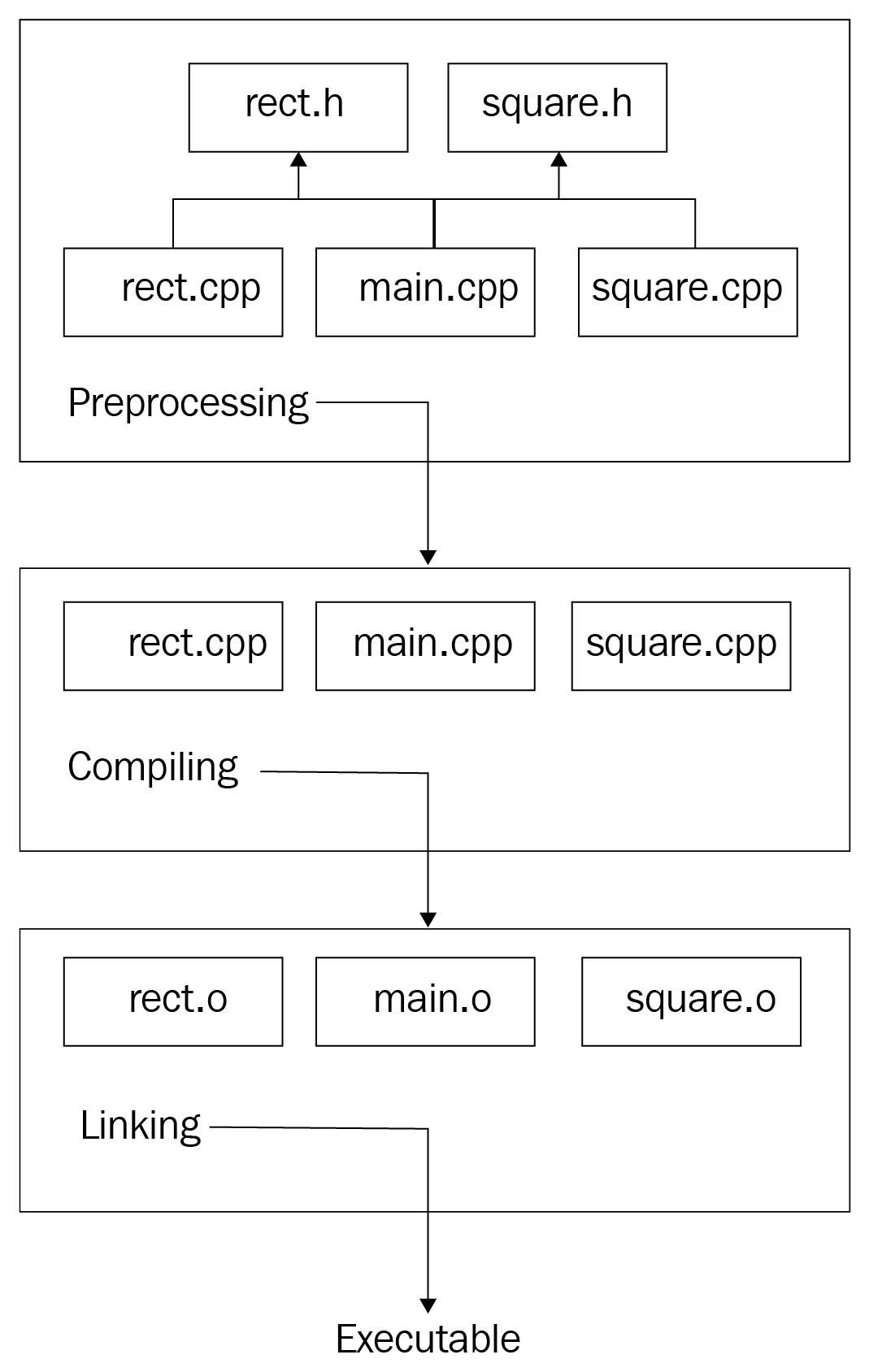

Compiler optimizations are done in both intermediate code and generated machine code. So what is it like when we compile the project? Earlier in the chapter, when we discussed the preprocessing of the source code, we looked at a simple structure containing several source files, including two headers, rect.h and square.h, each with its .cpp files, and main.cpp, which contained the program entry point (the main() function). After the preprocessing, the following units are left as input for the compiler: main.cpp, rect.cpp, and square.cpp, as depicted in the following diagram:

The compiler will compile each separately. Compilation units, also known as source files, are independent of each other in some way. When the compiler compiles main.cpp, which has a call to the get_area() function in Rect, it does not include the get_area() implementation in main.cpp. Instead, it is just sure that the function is implemented somewhere in the project. When the compiler gets to rect.cpp, it does not know that the get_area() function is used somewhere.

Here's what the compiler gets after main.cpp passes the preprocessing phase:

// contents of the iostream

struct Rect {

private:

double side1_;

double side2_;

public:

Rect(double s1, double s2);

const double get_area() const;

};

struct Square : Rect {

Square(double s);

};

int main() {

Rect r(3.1, 4.05);

std::cout << r.get_area() << std::endl;

return 0;

}

After analyzing main.cpp, the compiler generates the following intermediate code (many details are omitted to simply express the idea behind compilation):

struct Rect {

double side1_;

double side2_;

};

void _Rect_init_(Rect* this, double s1, double s2);

double _Rect_get_area_(Rect* this);

struct Square {

Rect _subobject_;

};

void _Square_init_(Square* this, double s);

int main() {

Rect r;

_Rect_init_(&r, 3.1, 4.05);

printf("%d\n", _Rect_get_area(&r));

// we've intentionally replace cout with printf for brevity and

// supposing the compiler generates a C intermediate code

return 0;

}

The compiler will remove the Square struct with its constructor function (we named it _Square_init_) while optimizing the code because it was never used in the source code.

At this point, the compiler operates with main.cpp only, so it sees that we called the _Rect_init_ and _Rect_get_area_ functions but did not provide their implementation in the same file. However, as we did provide their declarations beforehand, the compiler trusts us and believes that those functions are implemented in other compilation units. Based on this trust and the minimum information regarding the function signature (its return type, name, and the number and types of its parameters), the compiler generates an object file that contains the working code in main.cpp and somehow marks the functions that have no implementation but are trusted to be resolved later. The resolving is done by the linker.

In the following example, we have the simplified variant of the generated object file, which contains two sections—code and information. The code section has addresses for each instruction (the hexadecimal values):

code:

0x00 main

0x01 Rect r;

0x02 _Rect_init_(&r, 3.1, 4.05);

0x03 printf("%d\n", _Rect_get_area(&r));

information:

main: 0x00

_Rect_init_: ????

printf: ????

_Rect_get_area_: ????

Take a look at the information section. The compiler marks all the functions used in the code section that were not found in the same compilation unit with ????. These question marks will be replaced by the actual addresses of the functions found in other units by the linker. Finishing with main.cpp, the compiler starts to compile the rect.cpp file:

// file: rect.cpp

struct Rect {

// #include "rect.h" replaced with the contents

// of the rect.h file in the preprocessing phase

// code omitted for brevity

};

Rect::Rect(double s1, double s2)

: side1_(s1), side2_(s2)

{}

const double Rect::get_area() const {

return side1_ * side2_;

}

Following the same logic here, the compilation of this unit produces the following output (don't forget, we're still providing abstract examples):

code:

0x00 _Rect_init_

0x01 side1_ = s1

0x02 side2_ = s2

0x03 return

0x04 _Rect_get_area_

0x05 register = side1_

0x06 reg_multiply side2_

0x07 return

information:

_Rect_init_: 0x00

_Rect_get_area_: 0x04

This output has all the addresses of the functions in it, so there is no need to wait for some functions to be resolved later.