Getting started with coding the game

Open up Visual Studio if it isn’t already open. Open up the Timber!!! project by left-clicking it from the Recent list on the main Visual Studio window.

Find the Solution Explorer window on the right-hand side. Locate the Timber.cpp file under the Source Files folder.

Important note

.cpp stands for C plus plus.

Delete the entire contents of the code window and add the following code so that you have the same code yourself. You can do so in the same way that you would with any text editor or word processor; you could even copy and paste it if you prefer. After you have made the edits, we can talk about it:

// This is where our game starts from

int main()

{

return 0;

}

This simple C++ program is a good place to start. Let’s go through it line by line.

Making code clearer with comments

The first line of code is as follows:

// This is where our game starts from

Any line of code that starts with two forward slashes (//) is a comment and is ignored by the compiler. As such, this line of code does nothing. It is used to leave in any information that we might find useful when we come back to the code at a later date. The comment ends at the end of the line, so anything on the next line is not part of the comment. There is another type of comment called a multi-line or c-style comment, which can be used to leave comments that take up more than a single line. We will see some of them later in this chapter. Throughout this book, I will leave hundreds of comments to help add context and further explain the code.

The main function

The next line we see in our code is as follows:

int main()

int is what is known as a type. C++ has many types and they represent different types of data. An int is an integer or whole number. Hold that thought and we will come back to it in a minute.

The main() part is the name of the section of code that follows. The section of code is marked out between the opening curly brace ({) and the next closing curly brace (}).

So, everything in between these curly braces {...} is a part of main. We call a section of code like this a function.

Every C++ program has a main function and it is the place where the execution (running) of the entire program will start. As we progress through this book, eventually, our games will have many code files. However, there will only ever be one main function, and no matter what code we write, our game will always begin execution from the first line of code that’s inside the opening curly brace of the main function.

For now, don’t worry about the strange brackets that follow the function name (). We will discuss them further in Chapter 4, Loops, Arrays, Switches, Enumerations, and Functions – Implementing Game Mechanics, when we get to see functions in a whole new and more interesting light.

Let’s look closely at the one single line of code within our main function.

Presentation and syntax

Take a look at the entirety of our main function again:

int main()

{

return 0;

}

We can see that, inside Main, there is just one single line of code, return 0;. Before we move on to find out what this line of code does, let’s look at how it is presented. This is useful because it can help us prepare to write code that is easy to read and distinguished from other parts of our code.

First, notice that return 0; is indented to the right by one tab. This clearly marks it out as being internal to the main function. As our code grows in length, we will see that indenting our code and leaving white space will be essential to maintaining readability.

Next, notice the punctuation on the end of the line. A semicolon (;) tells the compiler that it is the end of the instruction and that whatever follows it is a new instruction. We call an instruction that’s been terminated by a semicolon a statement.

Note that the compiler doesn’t care whether you leave a new line or even a space between the semicolon and the next statement. However, not starting a new line for each statement will lead to desperately hard-to-read code, and missing the semicolon altogether will result in a syntax error and the game will not compile or run.

A section of code together, often denoted by its indentation with the rest of the section, is called a block.

Now that you’re comfortable with the idea of the main function, indenting your code to keep it tidy, and putting a semicolon on the end of each statement, we can move on to finding out exactly what the return 0; statement actually does.

Returning values from a function

Actually, return 0; does almost nothing in the context of our game. The concept, however, is an important one. When we use the return keyword, either on its own or followed by a value, it is an instruction for the program execution to jump/move back to the code that got the function started in the first place.

Often, the code that got the function started will be yet another function somewhere else in our code. In this case, however, it is the operating system that started the main function. So, when return 0; is executed, the main function exits and the entire program ends.

Since we have a 0 after the return keyword, that value is also sent to the operating system. We could change the value of 0 to something else and that value would be sent back instead.

We say that the code that starts a function calls the function and that the function returns the value.

You don’t need to fully grasp all this function information just yet. It is just useful to introduce it here. There’s one last thing on functions that I will cover before we move on. Remember the int from int main()? This tells the compiler that the type of value that’s returned from main must be an int (integer/whole number). We can return any value that qualifies as an int; perhaps 0, 1, 999, 6,358, and so on. If we try and return something that isn’t an int, perhaps 12.76, then the code won’t compile, and the game won’t run.

Functions can return a big selection of different types, including types that we invent for ourselves! That type, however, must be made known to the compiler in the way we have just seen.

This little bit of background information on functions will make things smoother as we progress.

Running the game

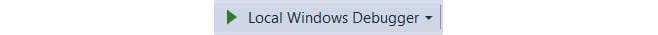

You can even run the game at this point. Do so by clicking the Local Windows Debugger button in the quick-launch bar of Visual Studio. Alternatively, you can use the F5 shortcut key:

You will just get a black screen. If the black screen doesn’t automatically close itself, you can tap any key to close it. This window is the C++ console, and we can use this to debug our game. We don’t need to do this now. What is happening is that our program is starting, executing from the first line of main, which is return 0;, and then immediately exiting back to the operating system.

We now have the simplest program possible coded and running. We will now add some more code to open a window that the game will eventually appear in.