std::atomic<int> speed (0); defines a speed variable as an atomic integer. Although the variable will be atomic, this initialization is not atomic! Instead, the following code: speed +=10; atomically increases the speed of 10. This means that there will not be race conditions. By definition, a race condition happens when among the threads accessing a variable, at least 1 is a writer.

The std::cout << "current speed is: " << speed; instruction reads the current value of the speed automatically. Pay attention to the fact that reading the value from speed is atomic but what happens next is not atomic (that is, printing it through cout). The rule is that read and write are atomic but the surrounding operations are not, as we've seen.

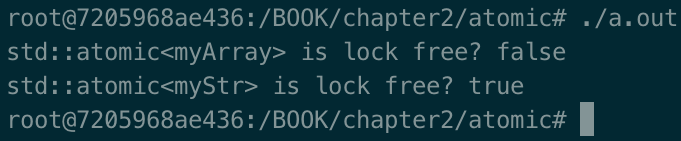

The output of the second program is as follows:

The basic operations for atomic are load, store, swap, and cas (short for compare and swap), which are available on all types of atomics. Others are available, depending on the types (for example, fetch_add).

One question remains open, though. How come myArray uses locks and myStr is lock-free? The reason is simple: C++ provides a lock-free implementation for all the primitive types, and the variables inside MyStr are primitive types. A user will set myStr.a and myStr.b. MyArray, on the other hand, is not a fundamental type, so the underlying implementation will use locks.

The standard guarantee is that for each atomic operation, every thread will make progress. One important aspect to keep in mind is that the compiler makes code optimizations quite often. The use of atomics imposes restrictions on the compiler regarding how the code can be reordered. An example of a restriction is that no code that preceded the write of an atomic variable can be moved after the atomic write.

Free Chapter

Free Chapter